In the early hours of July 4, 1954, the sun rose over Bay Village, Ohio, a quiet, suburban lakeside community on Lake Erie not far from Cleveland. It was a weekend bubbling with summer enthusiasm, packed with picnics, and a holiday ahead, until this peace was marred by an urgent phone call made just before dawn.

Four months pregnant, Marilyn Reese Sheppard had been found brutally beaten to death in her bed, at their lakeside home overlooking Lake Erie. The house, typically an epitome of suburban tranquillity, was smeared with blood all around.

Her husband, Dr Samuel Holmes “Sam” Sheppard, a well-respected osteopath and physician in the area, was found nearby, visibly shaken and injured. He had reportedly been knocked unconscious while trying to fight off an attacker, whom he described as a “bushy-haired” man. Dr Sheppard said he chased the attacker out of the house and down to the water’s edge before collapsing.

Physical Evidence and the Case Against Sheppard

From the very beginning, however, inconsistencies clouded the official facts of the event. There were no clear signs of forced entry into the home, and police quickly began to see certain disparities between Sheppard’s account and the physical evidence.

Firstly, he said he had awakened to the screams of his wife, given chase to a “bushy-haired intruder” down to the beach, and been struck unconscious for the second time. However, there were no indications of a forced entry into the Bay Village home, which made the possibility of a random late-night burglar seem somewhat bizarre. Secondly, there were no signs that Sheppards’ household dog had barked, something that was logically expected if any unknown person entered the home.

Surprisingly, the couple’s seven-year-old son, Samuel Reese (Chip) Sheppard, had been sleeping in the house the night of the murder, but did not wake up or recall any details from that night.

Furthermore, the account provided by Sheppard contained aspects that the police felt did not make sense when corroborated with physical evidence obtained from the crime scene. For instance, Sheppard claimed to have worn a T-shirt as he struggled with the assailant, but the police couldn’t find the said T-shirt at the crime scene. When asked about it, Sheppard offered evasive explanations.

At trial, the prosecution seized upon this absence, along with other unexplained elements (such as the lack of sand in his hair despite his claim of chasing the attacker to the water), as blatant inconsistencies that called his account into question.

Investigators further identified that the heavy blood spatter in the bedroom (evidence of a violent close quarters attack) did not correspond, beyond a single stain, to the blood on Sheppard’s own clothes. In such a violent confrontation as the police described, they would expect far more extensive blood transfer onto his clothing. Aside from limited staining, there was no heavy saturation on his trousers, shoes or socks consistent, in their view, with direct contact during the attack.

Finally, there was the question of timing. According to police sources, Sheppard had not called the police authorities immediately after the attack but had instead made an early call to a neighbour and close family friend, Dr Lester Houk. To detectives, this seemed an unusual instinct in a moment of crisis; he appeared to have reached first for personal help rather than calling the police directly.

Later, prosecutors claimed the order of events was significant, implying that uncertainty had existed even before reporting began. Defence lawyers countered by stating that his behaviour had been under stress, rather than guilt. Reaching out to someone familiar, they noted, did not point to wrongdoing; confusion frequently guides choices when under strain.

Investigators further noted that Sheppard’s wristwatch had stopped at approximately 4:15 a.m. Despite his claim of being rendered unconscious during an altercation with the intruder, questions arose over the reliability of this timepiece as proof and whether the chronology he offered was fully consistent.

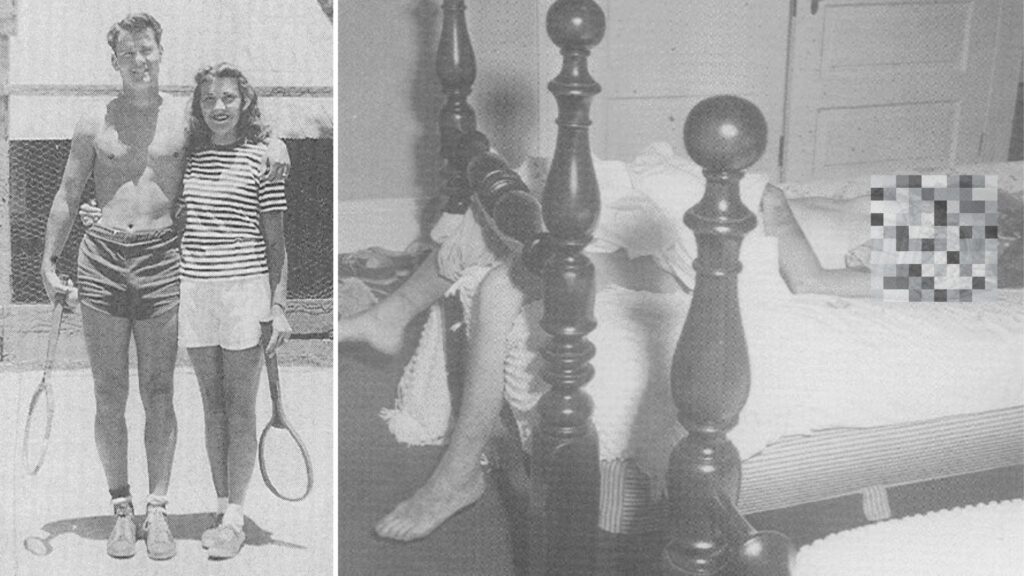

Click to view the crime-scene photo from the Sheppard bedroom (graphic).

An Unstable Investigation

However, this was not a Christie paperback in which a moustached Belgian would arrive, survey the drawing room, and declare the case solved before breakfast.

In the Sheppard case, much of what appeared incriminating in the first days also sat uncomfortably within the unquestionable reality of trauma, in the sense that memory fails under shock, that one does not always remember timelines, and that ordinary decisions, such as whom one calls first and what one remembers wearing, or what one notices in panic, do not always follow the logic of police proceedings.

It is also worth noting that the investigation itself was conducted in imperfect conditions. Friends, neighbours, and officials moved through the house freely in the hours after the killing, long before modern standards of scene preservation were the norm. In such circumstances, physical evidence was not simply discovered but even disturbed or distorted at times. Small gaps in records can widen into larger narratives, as one would observe in this case.

Moreover, certain aspects of the case left the conclusion unclear. Sheppard himself had visible injuries when police arrived, including a neck fracture and other physical trauma that his defenders argued were consistent with a violent struggle. The intruder theory initially proposed by Sheppard, while doubted, could not be entirely dismissed in a house that sat very close to the lake, was accessible, and was not completely sealed off.

To add fuel to the fire, the press soon fixated on Sheppard’s private life. Reports emerged that he had been involved in an extramarital relationship with Susan Hayes, a laboratory technician at the Bayes Hospital. Prosecutors used this to cite the motive for the murder, and in the atmosphere of 1950s suburbia, the line between a marital scandal and murder conviction proved to be dangerously thin.

Questions arose on whether investigators, under intense local pressure, settled too quickly on Sheppard as their central suspect. Alternative possibilities, including the presence of other individuals familiar with the home, were not fully explored in the earliest stages.

The Makings of a Public Verdict

None of this proved Sheppard’s innocence. But it did shake the confidence with which his guilt was asserted, and it helped explain why, over time, the murder of Marilyn Sheppard became not only a notorious crime, but a relevant legal argument in many places, about uncertainty in police procedure and the dangers of deciding upon a particular suspect too early.

Had this case been stuck in the slow gears of police procedure for any longer, this uncertainty might have enlightened the force back then, too. But that, unfortunately, was not to be. Almost immediately, the murder jumped from the confines of Bay Village and entered the pages of Cleveland’s newspapers, where it was treated not as an unresolved investigation but as a crime against society that demanded immediate resolution.

In the days after the killing, the press published a series of front-page editorials, including “Why is Sam Sheppard not in jail?”, “Why No Inquest? Do It Now, Dr Gerber,” and later “Quit Stalling – Bring Him In.” Hours after one such editorial, the county coroner announced a public inquest.

Bay Village officials and Bay View hospital staff had “combined to make law enforcement in this county look silly.” They further claimed that “no murder suspect in the history of this county had been treated so tenderly.” In Sheppard v. Maxwell, the Court noted Sam was arrested at 10 o’clock in the evening after these editorials ran.

The intensity of coverage was such that the U.S. Supreme Court would later cite it as an example of “massive, pervasive and prejudicial publicity” that made a fair trial virtually impossible. The names and addresses of prospective jurors were printed in local newspapers, exposing them to public pressure before the trial even began.

Outside Ohio, columns by noted journalists also began to emerge later. Columnist Dorothy Kilgallen had covered the trial extensively, and years after the original trial, Kilgallen said that before jury selection had even begun, the trial judge, Edward J. Blythin, had privately told her that he thought Dr Sam Sheppard was “guilty as hell.”

This claim was later used by Sheppard’s defence lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, in habeas corpus filings to argue that the courtroom had been prejudiced in their judgment.

“ONE POSSIBLE MOTIVE IS FEMININE JEALOUS HATRED, SPARKED TO ACTION BY SOME EVENT DISTURBING TO THE KILLER. A JEALOUS KILLING REQUIRES A WOMAN KILLER.”

The 1954 Conviction

After two months of testimony and cross-examination, during which the press practically filled every seat in the courtroom, the jury retired to deliberate. On December 21, 1954, after 96 hours of extensive discussion, the jurors found the accused guilty.

Dr Sheppard was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of his wife and sentenced to life imprisonment. At the time, the result seemed to satisfy the narrative that had dominated headlines for months, and everybody felt that justice had been ‘served’.

However, even after conviction, Sheppard continued to assert his innocence and pursued every available appeal possible. His early efforts in state court were quickly rejected, and an attempt to bring new evidence (including a 1955 affidavit from a criminologist suggesting that blood patterns might implicate someone other than Sheppard) did not persuade Ohio’s courts to grant a new trial.

Over the next decade, defence counsel continued to press on Sheppard’s case, on constitutional grounds. In 1964, after years of litigation in federal district courts, a judge finally granted a writ of habeas corpus, finding that excessive publicity and the courtroom environment had deprived Sheppard of a fair trial. That decision was reversed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, forcing Sheppard’s legal team to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

A Different Courtroom, with A Different Outcome

In Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966), the Supreme Court held that Sheppard’s constitutional right to due process had been violated because the trial judge failed to protect him from the “massive, pervasive and prejudicial publicity” that had plagued the proceedings. The Court took into cognisance that trial courts had an obligation to take precautions, including limiting media access, sequestering jurors, and controlling the dissemination of information, to ensure that the press’s right to freedom of expression did not outweigh a defendant’s right to a fair trial. It reversed the conviction and remanded the case for retrial.

During the 1966 retrial, the atmosphere was considerably different from the fevered frenzy of 1954. The public interest surrounding the case had receded, and media access was largely blocked. The jurors were more carefully shielded from outside influence, and the courtroom no longer bore any signs of the prejudice that the Supreme Court had previously condemned.

Sheppard did not take the witness stand. His defence counsel instead focused on undermining the prosecution’s physical and circumstantial case.

The prosecution, meanwhile, faced the challenge of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt without the overwhelming support of public certainty that had accompanied the first trial. Many of the case’s core points remained circumstantial, and alternative explanations began to seem more viable.

After about 12 hours of deliberation, the jury returned a not-guilty verdict, ending more than a decade of legal battle and leaving the question of guilt or innocence unresolved in the public mind.

Acquited…(?)

Despite the acquittal in 1966, uncertainty continued to cloud the case. Sheppard maintained his innocence for the rest of his life, and in the years after his release, his supporters pointed to evidence that prosecutors never fully resolved.

Additionally, over the decades, several other individuals were considered, both formally and informally, as potential suspects. Among these, the most talked about was Richard Eberling, a handyman and window washer who had been familiar with the Sheppard residence.

In later years, it was ‘discovered’ that Eberling possessed items that once belonged to Marilyn Sheppard, including some of her jewellery, which he admitted he had taken during unrelated burglaries; police also documented that he admitted bleeding inside the home while cutting himself shortly before the murder. However, Eberling repeatedly denied killing Marilyn and ran afoul of credibility issues.

Even decades later, subsequent legal actions have not shed light on the unresolved facts of the case. In a 2000 civil trial brought by Sam Sheppard’s heirs, attorneys presented DNA evidence showing the presence of blood at the scene that could not be tied conclusively to either Sam or Marilyn, though the court ultimately ruled that the family had not met the burden of proof to establish Sam’s innocence or to definitively implicate another person.

The Case That Changed American Courtrooms

The case established a lasting legal precedent, in that trial courts have an affirmative duty to protect defendants from what the Court called “massive, pervasive and prejudicial publicity.” Judges, the Court warned, cannot remain passive when the courtroom becomes indistinguishable from an informal, slanderous space. Instead, they must take concrete steps to restrict press access, control the courtroom environment, and shield jurors from outside influences.

The case’s impact can be felt in nearly every “trial of the century” that followed. When courts later confronted cases saturated with national attention, such as O.J. Simpson, Casey Anthony, or Derek Chauvin, Sheppard v. Maxwell remained one of the primary precedents invoked to weigh whether publicity had become prejudicial to the person on trial.

However, for all its legal significance, the fact remained that Marilyn Sheppard’s killer could never be definitively found. Sam Sheppard was acquitted, but is not believed by the majority, even today.

A paradox emerged regarding the press’s involvement. Certain in its pursuit of justice, the press helped create the very conditions that undid the conviction it demanded. By declaring Sheppard guilty even before the investigation, it created an atmosphere that the Supreme Court later deemed constitutionally intolerable.

Sheppard’s acquittal was not some sort of triumphant rediscovery of a truth being pursued. Instead, it was a meek outcome of systemic collapse, not total vindication. An indelible impact that it clearly left is a reminder that public outrage, however righteous it believes itself to be, can distort the very process it claims to defend, and that in the courtroom, justice cannot survive if the verdict is decided outside it first.