In the spring of 1995, a curator from the New York State Museum climbed several flights of stairs inside a deteriorating brick building on the grounds of the Willard Psychiatric Center, on the eastern shore of Seneca Lake. He followed a longtime Willard employee into an attic that ended at a brick wall and a closed door.

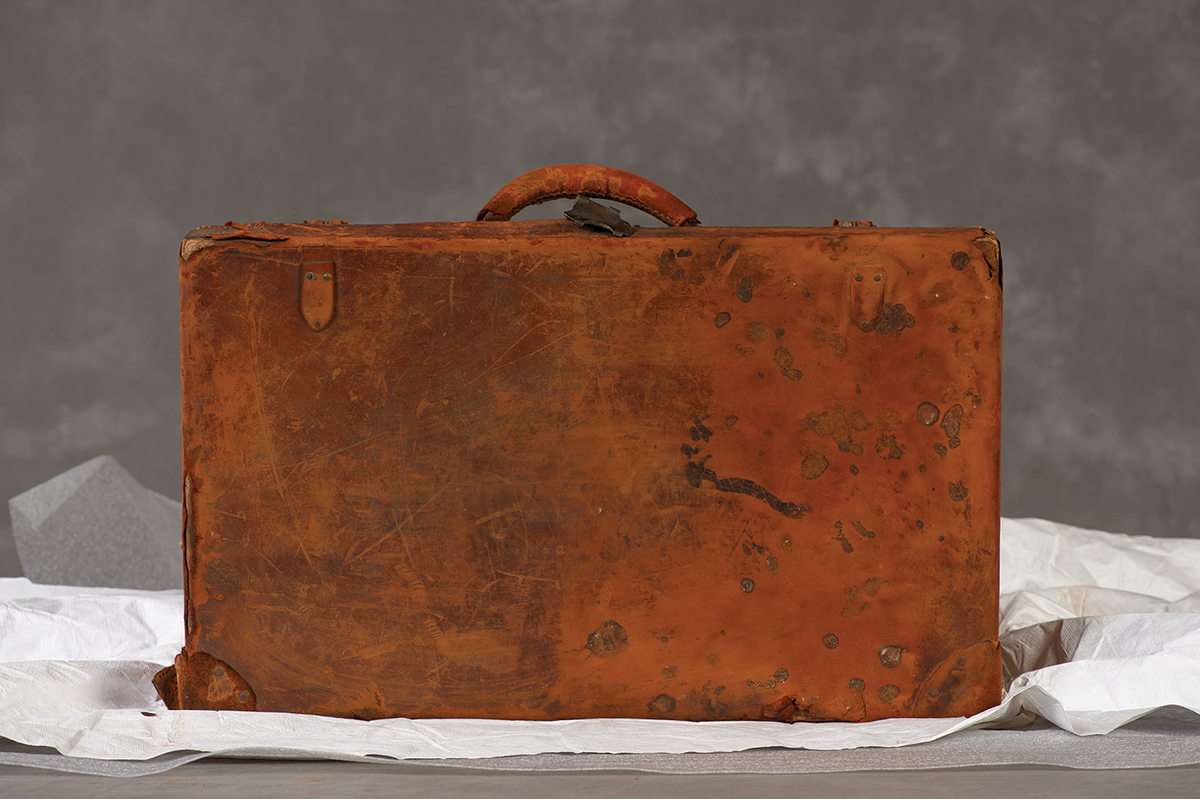

Craig Williams stepped through that door alone, according to later accounts, and found a room lined with rough shelving. Hundreds of suitcases sat in rows, dusted with debris from broken windows and roof damage, each tagged with a patient’s name and date of admission.

Willard staff had stored the luggage when patients arrived, then left it untouched for decades, in some cases for lifetimes. The institution was built for long stays, and the attic held the practical proof: people came with belongings and did not leave with them.

Williams did what a state employee is trained to do when he stumbles into an unexpected cache. He called his supervisors in Albany and asked what to do. The instruction he says he received was blunt: save a small sample and destroy the rest.

He refused. Within days, he returned with help, wrapping and moving what he could. A few elderly patients still living at Willard had their suitcases returned to them, he later told reporters; the rest, 427 containers in all, were shipped to museum storage outside Albany.

That choice, made in an attic behind a brick wall, is why Willard’s suitcases became more than a curiosity. They turned into evidence of how a state system handled people whose lives were meant to be kept out of sight, and how hard it can be to restore names once the system has replaced them with numbers.

The Door in the Brick Wall

Willard opened in 1869 as a state-run institution in rural upstate New York, one part of a broader era when governments built sprawling hospitals far from cities to house people deemed chronically mentally ill. By the late 20th century, that model had become politically and financially brittle.

In February 1995, Gov. George Pataki announced plans to close Willard, according to a detailed reconstruction published years later. The state planned to convert part of the campus for a drug treatment program for prisoners and to shutter other sections permanently.

Before anything could be repurposed or demolished, the state had to decide what to do with what Willard left behind, from equipment to records to personal property. Williams spent much of that spring documenting artifacts as part of that closeout work.

Beverly Courtwright, a longtime storehouse clerk at Willard, directed him to the building that had housed medical labs and occupational therapy rooms, accounts say. She led him up the stairs to the attic, then to the door set into the brick wall.

The suitcases were stored in a way that suggested routine, not sentiment. In one description, men’s suitcases sat on one side and women’s on the other, alphabetized and labeled, as if someone expected to retrieve them later. It was 1995 when researchers finally did.

The state’s initial impulse, as Williams recounted it, was disposal. His supervisors told him to keep a fraction, “10 suitcases at most,” and eliminate the rest, he said. Another account, written years later, put it more plainly: his boss told him to take 10, and he took them all.

That decision made the next steps possible. Staff and museum workers moved the cases off site, and the museum stored them in Rotterdam, outside Albany. Volunteers and interns catalogued a small number of cases, while many remained unopened.

What Patients Carried In

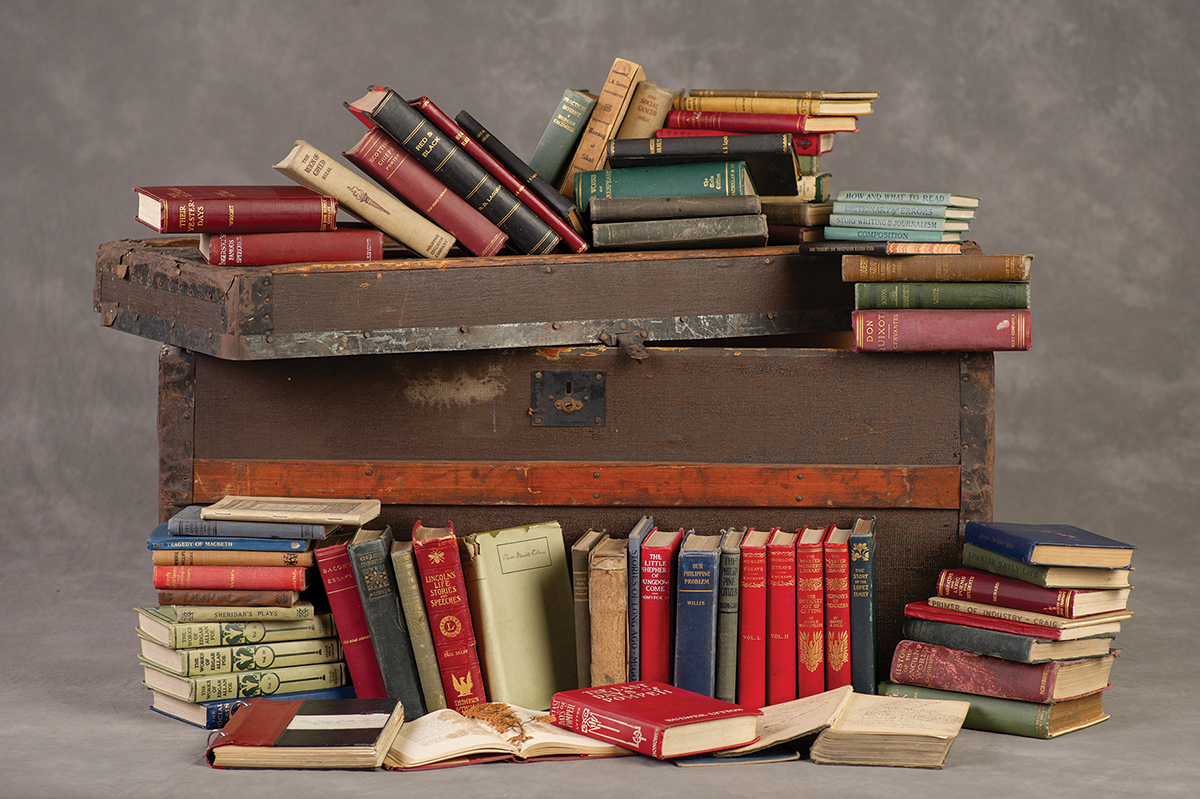

Most of the suitcases came from the early and mid-20th century, roughly 1910 through 1960, according to museum-related accounts and later reporting. That span captures the years when state hospitals were crowded and when long-term confinement often replaced community life.

A suitcase, as an object, carries a quiet kind of argument. It suggests a temporary stay, a person who expects to leave, a future that still contains choices. The luggage in Willard’s attic sat as if the future stopped mid-sentence.

When researchers began opening selected cases, they found the ordinary and the intimate: shoes, letters, photographs, small keepsakes, and personal grooming items, alongside the kinds of papers that once anchored people to a place and time. The items were mundane enough to feel familiar and specific enough to feel personal.

The cases also showed the limits of what the public can know. Medical charts and state files exist, but confidentiality laws restrict how names and details can be shared. Even the researchers who studied the suitcases wrote that they used pseudonyms for last names because of legal restrictions.

Those limits did not erase patterns. The researchers who reviewed the suitcases wrote that many owners had held jobs before they were institutionalized, working in trades and professions, and that their belongings reflected ambitions, education, and family ties. The transition from citizen to patient often looked abrupt.

One narrative thread that emerged from the early research was how small moments could become permanent outcomes. A police call, a hospital referral, a diagnosis written in the language of the era, then a transfer “upstate” into the state hospital system, where a stay could become a life sentence.

That is part of why the suitcases drew attention beyond museums. They offered something the public rarely sees from an institution built to contain: the before, preserved by accident, in objects that escaped official editing.

Ten Suitcases, or All of Them

In 1997, New York’s mental health commissioner at the time, James Stone, approved a study of the Willard luggage, according to reporting from that period. Williams partnered with Peter Stastny, a psychiatrist and documentary maker, to begin piecing together selected lives.

Stastny and Darby Penney, an advocate with a long professional history in mental health rights work, became central figures in interpreting what the suitcases could reveal. Their work tied objects to the institutional history around them, without pretending that a suitcase could explain everything.

They used a mix of methods that sounded less like art history and more like investigative reporting. They read charts when permitted, searched ship manifests, traced letters, examined photographs, and visited former homes, according to their published account. The suitcases served as the starting point, not the conclusion.

In 2004, the New York State Museum opened an exhibit called “Lost Cases, Recovered Lives,” structured around a small group of Willard suitcases. Museum materials described the goal as restoring a human dimension to people who had been hidden and forgotten.

The project expanded into a traveling exhibition and later into a book, “The Lives They Left Behind,” which told the stories of 10 patients whose belongings had been stored in the attic. Their last names were changed, the authors said, to comply with confidentiality laws.

Public interest swelled in part because the suitcases complicated a familiar narrative about deinstitutionalization. The public heard about closing hospitals, shifting care into communities, and the end of a bygone era, but the suitcases showed how the older system had worked in daily practice.

Willard itself stood at the intersection of those eras. In the decades before its closure, New York and other states reduced state-hospital populations sharply, driven by legal rulings, federal funding incentives, and changing views of confinement. Willard closed as part of that long retreat.

The suitcases, though, did not close. Once the museum took custody, the collection became a new kind of institutional artifact: a set of personal belongings treated as public history, even while the identities tied to them remained legally constrained.

Rotterdam, and the Stories Inside

In 2011, Williams granted photographer Jon Crispin access to the Rotterdam warehouse where the suitcases were stored. Crispin began photographing both the cases and their contents, building an archive of images that made the collection visible to a much larger public.

Crispin faced the same dilemma the researchers did: how to honor the people represented without violating privacy restrictions. Accounts of his process describe careful concealment of surnames in images, while leaving first names and initials visible, and removing identifying details from materials he posted publicly.

The photographs brought in something the museum exhibits could not fully supply: scale. The sheer number of cases, the repetition of shoes and hairbrushes and letters, the sense that a state system processed thousands of lives through similar steps. Crispin eventually photographed all 427 cases, according to a later profile.

For families, the images became a lead, not an answer. Crispin told a reporter he received regular emails from descendants who recognized a name or a detail and wanted more information, hoping to connect an image to a relative’s story. That hunger for connection ran up against legal walls.

The most recent twist has been less about photography than ownership. In 2014, the New York State Museum said it became aware of “significant questions of ownership” regarding the suitcases, according to a 2024 account, and began work with state agencies to resolve issues related to title.

A museum representative told that reporter that the museum had determined the suitcases and their contents were personal property, not state property, and that the collection would remain closed until ownership could be established and individual owners, or their heirs, could be asked to donate them.

That position reframed the entire project. A collection that had been treated as a public record of institutional history was now, in the museum’s view, a set of private belongings in a legal limbo, with access contingent on tracing people whose identities were already masked by time and law.

Crispin has described the closure as an injustice, in part because it cuts off new work that could keep the lives behind the suitcases in public view. The museum’s stance, as described publicly, treats privacy and property as inseparable questions.

A Cemetery of Numbers

Across from the old Willard campus sits another archive of the people who passed through the institution: a cemetery that began in 1870, when Willard still used “Asylum” in its name. The burial ground includes sections organized by religion and a Civil War veteran section, according to state archival descriptions.

The state’s own finding aid for Willard burial and interment records puts the number plainly. Approximately 5,757 patients are buried in the cemetery, it says, and burial registers typically list names, ages, places of birth, dates, and plot information. The records became state archives material in January 2001.

The public rarely sees those names. The same finding aid states that access is restricted under New York’s Mental Hygiene Law Section 33.13, which governs confidentiality of clinical records and requires specific approvals for access. The existence of a ledger is one thing; public entry into it is another.

For many years, visitors to the cemetery saw the logic of anonymity made physical: markers with numbers rather than names, or missing markers in an overgrown field, depending on the section and the era. Even when the records exist, the ground itself can read like a list of placeholders.

Activists and local residents have worked to change that, sometimes by focusing on a single life that the public can name. One such figure is Lawrence Mocha, a longtime Willard patient who, according to accounts repeated in local reporting, dug graves for other patients during decades inside the institution.

In 2015, Colleen Spellecy and a committee she founded pushed to mark Mocha’s grave and to expand memorialization for the larger cemetery. A Catholic Courier report said the group’s goal was to memorialize by name all 5,776 deceased patients resting there, a figure used widely in community accounts even as archival descriptions list a slightly different count.

The work around the cemetery underscored how the Willard suitcases and Willard graves share a common problem. Both involve names written down in official places, and both face legal and institutional barriers that can keep those names from public recognition, even generations later.

The cemetery records also reveal how long Willard’s shadow lasted after the hospital itself closed. The archival description says the cemetery continued to be used and maintained after 1995, and that some patients at Willard during the closure requested burial there, with the facility honoring those wishes.

Names, Locked Behind a Law

The Willard suitcases became famous partly because they provided a way to talk about institutional confinement without relying on clinical files alone. Photographs of objects can be shared without revealing diagnoses, and a suitcase can suggest a life without exposing a chart. That approach has limits, too.

Researchers who studied the suitcases wrote that they could reconstruct some biographies through permitted records and public documents, but that they still had to obscure surnames because of legal restrictions. The public can learn patterns and fragments, while the full identification of many individuals stays protected.

Those protections intersect with another reality: stigma, both past and present. Atlas Obscura, writing about numbered asylum graves across New York in 2014, noted that families historically requested anonymity, and that bureaucracy and confidentiality laws have continued to complicate the public release of names.

The same article, citing reporting in The New York Times, said an estimated 55,000 patients were buried in anonymous graves in New York, and described Willard as a focal point for a campaign to restore names in a cemetery holding roughly 5,800 people. The number is an estimate, but the scale is not.

Willard’s suitcases, meanwhile, sit inside another kind of constraint: the museum’s more recent claim that the suitcases are personal property, not state property, and that ownership must be resolved before access can reopen. The public record of suffering and survival now hinges on inheritance law.

That conflict produces a strange symmetry. The hospital once stored belongings in an attic as patients moved into wards. Decades later, the museum stored those same belongings in a warehouse while the public tried to understand what happened inside the hospital, and while families tried to locate their own missing history.

The suitcases also challenge a tidy narrative about institutions simply vanishing. Willard did not disappear cleanly in 1995. The campus shifted uses, records moved into archives, and personal property moved into museum custody, where it triggered a long-running debate about who gets to decide what counts as public history.

In the simplest sense, each suitcase is a tagged name and a date, a tiny administrative act that survived an entire system’s decline. In the most complicated sense, the same tag now points to unanswered questions about consent, custody, and who has the right to open a life that the state once locked away.