On an April morning in 1908, a maid in a small Swedish coastal home heard sudden noise from the bedroom. Karolina Olsson was crying, moving, and trying to stand, as if waking from a single night.

She was 46 years old, yet visitors said she looked far younger. The family insisted she had been asleep since 1876. If that was true, her bed had become a time capsule for 32 years.

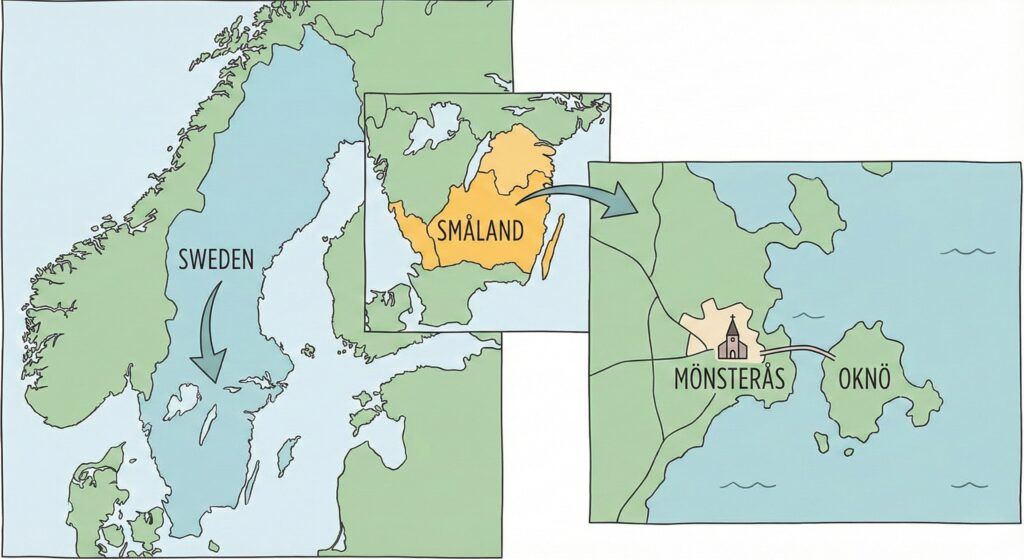

Karolina was born in 1861 on Oknö, a small island near Mönsterås on Sweden’s southeast coast. She was the second of five children, with four brothers, in a household shaped by fishing and weather.

In winter, life on the Baltic edge could feel enclosed, with long darkness and tight routines. Illness carried more fear than diagnosis, because doctors cost money and hospitals sat far away.

At 14, she suffered a head wound outdoors on 18 February 1876 and seemed to recover. Four days later she complained of tooth pain, and her family, fearing witchcraft, ordered her to bed.

When she closed her eyes that night, the household expected a stubborn teenager and a rough morning. Instead, hours passed, then days, with Karolina unmoving and unreachable, breathing quietly while the island carried on.

Her father, a fisherman, could not easily pay for medical help, so neighbors and a midwife became the first advisers. Her mother began forcing milk and sugar water, keeping the body alive while the mind stayed hidden.

Eventually, neighbors collected money for a doctor. He failed to rouse her and called it a coma, then kept returning for about a year. After that, he wrote to a leading Scandinavian medical journal asking for help.

Doctors came and went, each carrying a different theory and a different level of patience. Some observed that her hair and nails seemed unchanged. Family members said she sometimes sat up and murmured childhood prayers, then sank again.

One physician, Johan Emil Almbladh, later argued her condition resembled hysteria, a catchall label of the era that mixed moral judgment with medicine. The word offered certainty, yet it also left a wide space for guesswork.

In July 1892, she was taken to a hospital in Oskarshamn. Staff tried electroconvulsive therapy and documented a diagnosis of dementia paralytica, a term then linked to neurosyphilis. She was released on 2 August, unchanged.

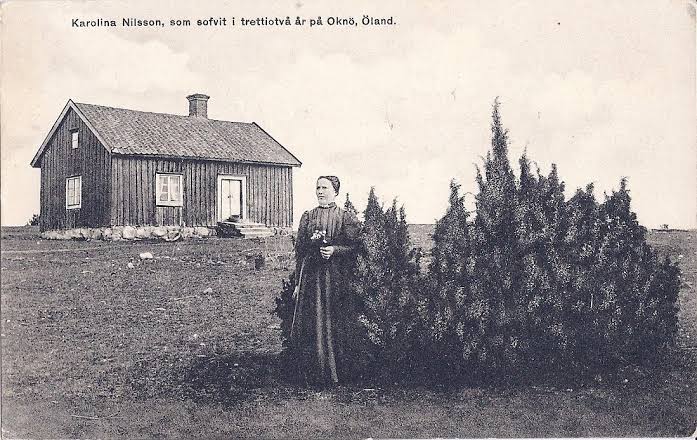

Back at home, the routine narrowed to maintenance. Accounts say she received two glasses of milk each day. After her mother died in 1904, a maid handled the house. When a brother died in 1907, Karolina cried.

That reaction became part of the puzzle, because grief suggested awareness beneath the stillness. Yet the household continued to describe her as asleep. The story solidified: a girl trapped in slumber, waiting for an unknown key.

On 3 April 1908, 32 years and 42 days after the first sleep, the maid found her awake. Karolina was crying and jumping on the floor. When her surviving brothers arrived, she failed to recognize them.

Witnesses described her as thin and pale, with light hurting her eyes during the first days. She was weak and struggled to speak at first. She could still read and write, and she remembered what she learned before 1876.

News moved fast for the era. Reporters arrived from Europe and the United States, and the family hid from the attention. She later underwent psychiatric testing in Stockholm, where doctors found her faculties intact and similar to before.

Doctors and journalists also fixated on her appearance. At 46, she was described as looking around 25, a detail that made the story travel further than any medical chart. Youth became a kind of proof, even when proof was scarce.

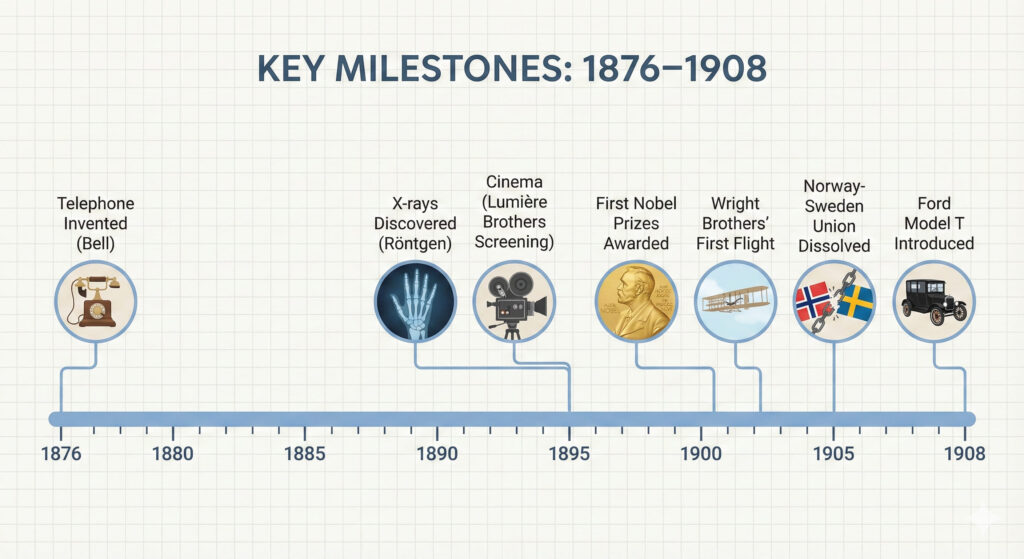

To understand why the tale still grips people, it helps to treat her bedroom like a lighthouse room, steady while the sea of history turns. Between 1876 and 1908, modern life arrived in waves.

In the year she first fell asleep, Alexander Graham Bell received a telephone patent, and voices began traveling through wires in a way that felt like magic. Conversation stopped being limited to walking distance, and news began to accelerate.

By 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had reported X-rays, giving doctors a way to see inside living bodies. For many families, illness slowly shifted from superstition toward images and measurements. In Karolina’s home, care still relied on observation.

That same year, paying audiences in Paris watched moving pictures projected on a screen, a famous early step into commercial cinema. A shared public imagination formed in dark rooms, while Karolina remained in private darkness on Oknö.

In 1896, Athens hosted the first modern Olympic Games, a revival meant to celebrate bodies in motion. Newspapers carried names of runners and wrestlers across borders. In Sweden, the contrast between athletic spectacle and a motionless girl grew sharper.

In 1901, the first Nobel Prizes were awarded, placing Scandinavia at the center of a new global ritual of science and letters. It was an age that celebrated discovery, yet Karolina’s case remained a local mystery with few records.

In 1903, the Wright brothers achieved controlled, sustained powered flight, and the idea of distance changed again. The sky began to look reachable. On Oknö, the household still measured distance by footsteps between kitchen and bed.

In 1905, Norway and Sweden dissolved their union after political crisis and a plebiscite, reshaping the region’s map and identity. For many Scandinavians, it was a once in a lifetime national turning point. Karolina’s world stayed indoors.

In 1908, the Ford Model T appeared, promising affordable travel for ordinary families and a future built on speed. Around that same spring, Karolina stood up in her room, blinking into light, hearing a new century outside.

Her story reaches us through family memories, scattered medical notes, and later retellings that prefer a clean number. Even the strongest versions rely on ordinary people describing extraordinary behavior over decades, without continuous supervision or modern monitoring.

The daily care details raise hard questions. Swallowing, hydration, and basic movement usually leave traces, even in severe illness. A person fed for years tends to wake at times, even briefly, and caretakers tend to adapt to what they see.

Psychiatrist Dr. Frödeström met her in 1910 and later published a 1912 paper about the case. Later accounts suggest she woke occasionally and reacted with sorrow. He even wondered if she kept her eyes closed to draw sympathy.

Locals called her Soverskan på Oknö, the Sleeper of Oknö, and the nickname outlived the medical uncertainty. A relative later wrote that questions still linger in the family, as her story inspired renewed attention, even an opera.

Any explanation has to hold two truths at once. Something serious happened to Karolina at fourteen, and the household spent decades organized around her body. At the same time, the legend of continuous sleep strains credibility in modern medicine.

One grounded theory places her in a prolonged stupor, similar to catatonia, where a person can appear unreachable for long periods while remaining alive and intermittently aware. This fits an era with limited psychiatric language and limited treatment options.

In that frame, the crying reported after a brother’s death reads as a brief surface break, a moment when emotion escaped the mask. Caretakers might have interpreted those moments as sleep talking or dreaming, then returned to the familiar routine.

Another theory points to withdrawal, where the body becomes a shelter from demands, conflict, or fear. Adolescence can be a hinge moment, and rural communities sometimes turned distress into folklore. A young person could disappear into stillness without leaving home.

A third possibility grows from the daily logistics. If she had periods of wakefulness, even short ones, the household might have kept them private. Over time, the simplest story becomes the permanent one, and later retellings compress the messy reality.

Some analysts suggest she may have learned to perform sleep, staying still because it reduced expectations and conflict. In a poor household, an ill child could attract sympathy and protection. Remaining withdrawn might have felt safer than returning to life.

Then there is the storytelling force itself. A sleeping girl who wakes decades later fits an archetype older than medicine, and journalists loved clean, dramatic numbers. Once the nickname traveled, every retelling polished the edges and deepened the mystery.

Even the origin story reflects that older world. Her family connected tooth pain to witchcraft, and the cure began with obedience, bed, and prayer, before any doctor arrived. That detail shows how belief can steer what people see and report.

The hospital label, dementia paralytica, also shows the era’s limits. It was often used for a severe neurosyphilis presentation linked to untreated infection, yet later summaries question whether her overall picture matched that pathway.

After the attention faded, Karolina lived quietly for decades, supporting herself as a seamstress and moving through the world that had advanced without her. She died in 1950 at 88, with reports attributing the cause to an intracranial hemorrhage.

Her case survives because it sits on a thin line between sleep, illness, and social performance. The bed can be read as a medical site, a family project, and a stage for community attention, all at once, over a generation.

With the record, certainty stays limited. A teenage girl entered a long disabling state in 1876 and emerged in 1908 with her memories intact. Everything beyond that rests on observation, interpretation, and the human urge to make a story coherent.

That coherence is part of the appeal. While telephones connected voices, X-rays revealed bones, and nations redrew borders, one Swedish household centered its days on a quiet room. The contrast makes the tale feel unreal, and therefore unforgettable.

Karolina Olsson woke and insisted only a night had passed, a line that can read as confusion, defense, or truth as she felt it. The deeper mystery may be her inner experience, rather than the exact number of years.