They told them it was safe. Then their jaws fell off.

In the early 20th century, America was buzzing with scientific optimism. Electricity, aviation, radio—every discovery seemed to promise a brighter, faster, healthier future. Among the most dazzling innovations was a new element ripped straight from the pages of science fiction: radium. It glowed. It healed. It was the future.

And for a time, it lit up more than clocks and compasses. It lit up young women—literally.

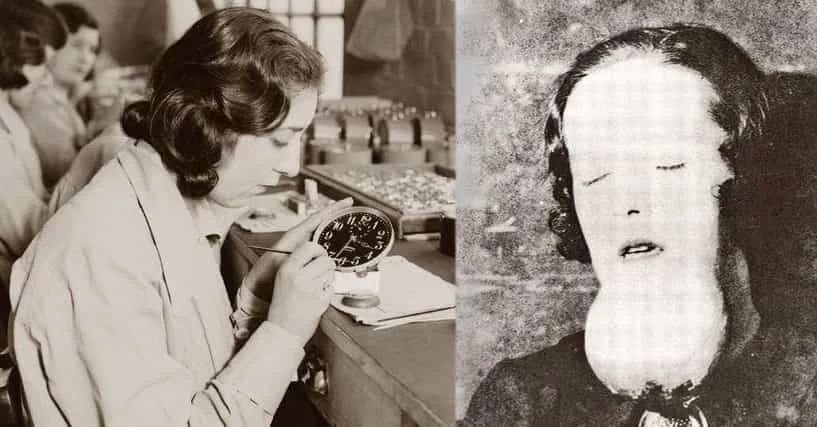

They were called “dial painters,” mostly girls in their teens and early twenties, employed in factories in New Jersey, Illinois, and Connecticut to paint watch dials and military instruments with radium-based luminescent paint. The paint—branded with names like Undark and Luna—needed a steady hand and a fine brush tip to mark the tiny numbers. To keep the tip sharp, supervisors taught the girls a trick: put the brush between your lips and twist it to a point.

“Lip, dip, paint.”

They repeated it hundreds of times a day.

Radium: The Miracle Poison

Discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1898, radium quickly developed a glamorous reputation. Doctors promoted it as a health tonic. Radium-laced water was bottled and sold as a cure for everything from arthritis to impotence. Beauty companies created radium-infused face creams and toothpaste. Even high-end spas marketed radium baths as a luxury treatment.

No one seemed concerned about its dangers—except for the Curies themselves. Marie Curie reportedly warned of its risks but was ignored in the face of public fascination. Radium was exotic, expensive, and electrifying. So when companies like United States Radium Corporation (USRC) in Orange, New Jersey, and Radium Dial Company in Ottawa, Illinois, began hiring women to work with the substance, few questioned the risks.

At USRC, the girls worked in bright, airy studios. Supervisors often told them they were lucky—doing patriotic work for the war effort, providing glowing dials for soldiers’ watches. Some even painted their fingernails, teeth, and faces with the luminous paint for fun, giggling at the glow when they walked home at night.

Then the pain began.

For Amelia “Mollie” Maggia, one of the first known victims, it started with a toothache. A dentist removed the tooth. Then another. And another. Her jaw began to disintegrate in his hands. The pain spread to her limbs, then to her entire body. Tumors developed in her face and hips. In May 1922, she died. She was 24.

Doctors were baffled. Mollie’s death certificate cited syphilis—a diagnosis her family contested bitterly. But they were silenced. USRC claimed the company had done nothing wrong. And besides, they said, the girls must be sick from something else. Maybe poor hygiene. Maybe promiscuity.

But Mollie wasn’t alone.

Her friends—coworkers like Grace Fryer, Edna Hussman, and Katherine Schaub—began showing the same symptoms: aching joints, loose teeth, jaw necrosis, spontaneous bone fractures. One woman’s spine collapsed. Another’s legs shortened. Still others developed anemia, ulcers, or bone cancers that rotted them from the inside out.

What they didn’t know yet was that radium replaces calcium in the body. Once inside, it lodges into bones and irradiates tissue constantly, killing cells and causing irreparable damage. But corporate doctors insisted otherwise. They conducted sham tests, claimed the girls were fine, and hired “experts” to blame the victims.

Coverups and Denials

United States Radium hired Dr. Frederick Flinn, a physiologist from Columbia University, to examine the workers. But he wasn’t independent—he was on USRC’s payroll. His report claimed the girls were in excellent health. Internally, however, the company was quietly paying funeral expenses and hiding documentation that linked radium to bone decay.

Privately, executives took precautions. Male chemists handling radium wore lead aprons, tongs, and protective masks. The women painting with it? No safety gear. No warnings. No informed consent.

In 1925, public attention intensified when Dr. Harrison Martland, a county medical examiner in New Jersey, devised a reliable test to detect radium in human tissue. His results were damning: the dial painters’ bones contained radioactive material. The women were dying not from mystery illnesses, but from internal radiation poisoning. It was conclusive.

And now, the women were angry.

A Fight Begins—But Time Is Against Them

Grace Fryer emerged as the reluctant but determined face of the fight. A former dial painter turned bank clerk, Grace had suffered for years as her spine deteriorated. But she kept meticulous records and refused to stay silent. She contacted lawyers—dozens of them. Most turned her down. Taking on USRC meant going up against big money, hired doctors, and industry loyalty.

Eventually, attorney Raymond Berry agreed to take her case. By that time, four more women—Edna, Katherine, Quinta McDonald, and Albina Larice—had joined her. They became known as “The Radium Girls.”

By the time their lawsuit was filed in 1927, their health had rapidly declined. All five were expected to die. Some had to be carried into court on stretchers.

But the world was finally paying attention.

They came to court broken. And they still had to prove they were dying.

By 1927, the five plaintiffs—Grace Fryer, Edna Hussman, Katherine Schaub, Quinta McDonald, and Albina Larice—could barely stand. Grace wore a steel back brace. Quinta had lost all her teeth. Katherine’s jawbone had been removed. They were in their twenties and thirties, but they looked decades older. And the company still refused to admit guilt.

United States Radium Corporation had everything on their side: top-tier lawyers, paid-off doctors, and the momentum of a country that still viewed industry as sacrosanct. The women? They had little time left.

And yet, they were the ones on the defensive.

The Cost of Being First

The Radium Girls’ lawsuit wasn’t just about compensation—it was about recognition. They wanted the truth recorded: that radium had killed them, and that the company had known it was dangerous all along.

Their legal team, led by Raymond Berry, presented damning evidence. Dr. Harrison Martland’s tests proved that radium was present in the women’s bones, teeth, and even exhaled breath. Court records show that internal memos from USRC executives acknowledged radium’s dangers long before the women were ever hired.

The company, desperate to avoid a legal precedent, tried to stall the case until the women died.

And they nearly succeeded.

A Settlement—But No Justice

Public opinion shifted only after the press descended on the trial. Reporters covered every detail—photographing the women, interviewing doctors, exposing company lies. Headlines like “Girls Glow in the Dark” and “They Knew It Was Poison” turned the court case into a national reckoning.

Under pressure, USRC offered a settlement: $10,000 to each woman (about $180,000 today), plus an annual $600 pension and medical expenses. It wasn’t justice. It was survival.

But it was historic.

For the first time, a U.S. company had been held financially accountable for occupational disease—and specifically, for knowingly endangering female workers.

Grace Fryer told the press:

“It is not for myself I care. I am thinking more of the hundreds of girls to come.”

And the Girls Kept Coming

Even as the New Jersey case was closing, another battle was brewing in Illinois, where dozens of women from the Radium Dial Company in Ottawa were suffering identical symptoms: jaw necrosis, anemia, spontaneous fractures, and death. The company denied responsibility. Doctors were again complicit. The pattern repeated.

This time, the legal fight went all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court, where the justices ruled in favor of the women in 1938—a full decade after the New Jersey case.

One of the Illinois victims, Catherine Donohue, gave testimony from her deathbed. She weighed just 71 pounds and could no longer walk. When the company’s attorney accused her of faking her illness, she lifted her hand and showed him her exposed jawbone.

It was the final blow.

The Ripple Effects: What the Radium Girls Left Behind

Their fight reshaped American labor policy:

- It led to the establishment of the Occupational Disease Labor Commission.

- It became one of the key precedents for the creation of OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) decades later.

- It shifted how courts handled employer liability, especially in cases involving scientific evidence and long-term exposure.

The case was also pivotal in shaping toxicology and radiological safety standards. For the first time, internal exposure to radioactive substances was acknowledged as a long-term health threat, and dosage thresholds were revised globally.

And yet—none of this came fast enough for the women it killed.

Hard Questions That Still Matter

- Why were the male scientists at these companies protected while young working-class women were left to rot?

- How many doctors and journalists were bought off before the truth saw daylight?

- Why does it always take death—and spectacle—for corporations to act?

And perhaps the most uncomfortable:

Would we believe them today?

In a world where women’s medical complaints are still dismissed, where whistleblowers face career-ending retaliation, and where profit margins often override safety—have we really changed?

What the Bones Still Say

Years later, long after the lawsuits ended and the paint was banned, the government exhumed the remains of several Radium Girls for testing. They still glowed in the dark.

Their skeletons were radioactive.

Their stories had become footnotes in labor law textbooks.

But their bones?

They were still testifying.