In 1975, a baby boy arrived in a Kentucky hospital with skin so darkly blue that staff feared an oxygen crisis. The child, Benjamin “Benjy” Stacy, looked startling, yet he otherwise appeared healthy, and the color began to fade in the weeks that followed.

By then, people in eastern Kentucky had been telling a story for generations about “blue people” living in the hills. Benjy’s birth pulled that story out of the hollows and back into clinical light, forcing doctors to sort folklore from physiology.

The tale often gets repeated with a single sensational explanation: incest. The record is less lurid and more specific, describing an isolated community where relatives sometimes married relatives, often cousins, because the local marriage pool stayed small for decades.

What made the Fugates famous was not a secret ritual or a hidden crime. It was a recessive gene, passed quietly through family lines, that could tint skin blue when two carriers had children together.

The newborn who made the old stories sound real again

Accounts of Benjy Stacy’s birth describe a baby who drew attention the moment nurses saw him. In one widely circulated retelling adapted from earlier reporting, medical students later crowded around him, trying to trigger the bluish tint in his lips and nails when he became upset or cold.

Benjy’s blue tone did not last. As he grew, it reportedly receded to a temporary tinge that could show up under stress or chill, a detail that helped physicians place him in a known medical category rather than a mystery category.

That category is methemoglobinemia, a condition in which an abnormal form of hemoglobin called methemoglobin cannot deliver oxygen effectively the way normal hemoglobin does. People can look blue even when they are not in immediate danger, depending on severity.

Doctors and journalists who covered the Fugates often emphasize a small, unsettling irony. The treatment used in severe cases is methylene blue, a vivid blue medication that helps convert hemoglobin back toward its functional form.

Troublesome Creek and the part that is documented

To understand how a blue baby could appear in 1975 and still be tied to a 19th century story, you have to follow a place name that shows up again and again: Troublesome Creek, a tributary system in eastern Kentucky associated in reporting with the cluster of families later nicknamed the “Blue People.”

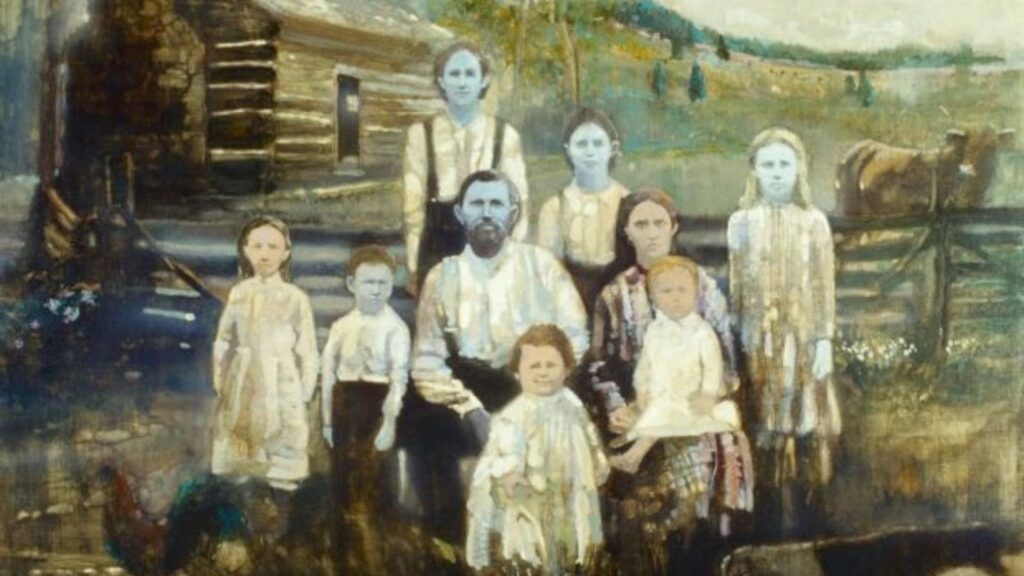

The names recur, too. Writers who traced the local history describe a tight circle of surnames around the creek and nearby hollows, including Fugate, Smith, Ritchie, and Stacy, all tied together by marriage over generations.

The origin story usually begins around 1820 with Martin Fugate and Elizabeth Smith. Multiple later accounts say they settled near Troublesome Creek and that several of their children were born with blue skin.

What is less firm is the part that gets told first in dramatic versions: that Martin Fugate was a French orphan, and that he arrived already blue. Medical writers themselves often flag this as “lore,” a phrase that matters because it signals a gap between community memory and verifiable documentation.

The core mechanism, though, does not depend on whether the founding couple’s biography is tidy. The condition involved is recessive, meaning a person can carry one copy of the gene and look typical, while two carriers can have children who show the trait.

In a large, mobile population, two carriers of a rare gene might never meet. In the mountains, with limited roads and a limited set of nearby families, the odds changed, and the same genetic coin flip happened again and again.

What “inbreeding” meant in this valley

It helps to be precise about what sources actually describe. In mainstream reporting, “inbreeding” is often used as shorthand, but the structure underneath it is mostly documented through marriages that stayed within a small kin network, including cousin marriages, rather than a catalog of explicit acts.

That distinction is not a moral defense so much as a factual boundary. Some relationships between cousins were legal and culturally normalized in many rural American settings across the 19th and early 20th centuries, and records typically track households and marriages, not private behavior.

What can be said, based on repeated reputable summaries, is that the same families married into each other for generations. As a result, two carriers of the same recessive trait were more likely to pair, which is the statistical condition needed for the most visible cases.

The sensational version of the story tends to flatten this into a single word and then stop. The medical version keeps going, because the next question is not who slept with whom, but why some people turned blue without dropping dead.

The answer lies in degree. The same disorder that can become dangerous at higher methemoglobin levels can also present as a mainly cosmetic change at lower levels, allowing people to live long lives while looking unusual to outsiders.

That nuance explains why the Fugates became a story instead of a series of medical emergencies. A person could walk into town, draw stares, raise rumors, and still carry on farming, marrying, raising children, and aging into old age.

The clinic encounter that turned rumor into a case file

By the mid 20th century, the blue people story had made its way into the world of clinicians, where it landed on the desk of a young hematologist at the University of Kentucky, Dr. Madison Cawein III.

Cawein faced a practical problem that every researcher in a rural legend faces. You cannot diagnose a rumor, you have to find a person, and the people who carried the most visible trait had reason to avoid strangers who treated them as a spectacle.

HistoryExtra’s account describes how chance bridged that gap. Two blue skinned siblings, Rachel and Patrick Ritchie, walked into the heart clinic where nurse Ruth Pendergrass worked, putting the story in front of trained eyes instead of at the end of a dirt road.

From there, Cawein built a study the way clinicians often do when genetics meets geography. He gathered family history, mapped relationships, and collected blood samples, trying to link what people saw on skin to what was happening inside red blood cells.

At the time, medical literature already described hereditary methemoglobinemia in other populations, including work by public health physician E. M. Scott on enzyme activity and recessive inheritance. That research gave Cawein a framework for what to test.

Scott’s 1960 paper described evidence consistent with recessive inheritance tied to enzyme levels, showing parents of affected children with about half normal enzyme activity in red cells. It was not a Kentucky paper, but it mattered to Kentucky.

The paradoxical cure that made them pink

The treatment story survives because it is vivid and because it worked quickly. Cawein used methylene blue, and in retellings based on Trost’s reporting, the skin color of affected people shifted within minutes, from blue to pink, in front of witnesses.

Methylene blue is not a cosmetic dye job. It functions as a chemical helper in the body’s process of reducing methemoglobin back toward a usable form, which is why it is used in clinical treatment for methemoglobinemia.

In the Fugates’ milder hereditary form, treatment was often about relief from stigma as much as relief from symptoms. Medical guidance notes that mild cases can require little intervention, while severe cases may call for methylene blue.

Cawein’s work did not stay local. His findings were published in 1964 in Archives of Internal Medicine under the title “Hereditary Diaphorase Deficiency and Methemoglobinemia,” anchoring the legend to a formal clinical description.

That publication also mattered for what it did not do. It did not treat the family as a circus act, and it did not frame the community as a genetic horror story, even though later pop retellings often slide in that direction.

Cawein died in 1985, ABC News later reported, but his charts and samples contributed to a clearer understanding of how recessive conditions can remain hidden until a community’s mating patterns make carriers overlap.

A family trait becomes a public spectacle

Even when a medical answer exists, a community still lives with the social answer, and those can diverge. A blue tinge on skin invites gossip because it resembles the visual language of suffocation, illness, or death, even when the person feels fine.

The Fugates became a shorthand example in reporting for the way rare traits can grow common in isolated pockets. The story is told in classrooms, in medical lectures, and in general interest pieces partly because it is easy to picture.

It also became a cautionary tale about stigma. In ABC News reporting, hematologist Dr. Ayalew Tefferi described the Fugate story as an intersection between disease and society, pointing to how misinformation can turn a condition into a label.

For people living with visible differences, the label can follow them into school, work, and family life. ABC News told the story of Kerry Green, born in 1964 in Tulsa with a related condition, who said he was picked on as a child because he was blue.

Green’s case also illustrates a second point that gets lost in Fugate focused retellings. “Methemoglobinemia” is not one single life experience; its causes and severity vary, and some genetic forms can be far more medically serious than the mild rural cases.

In the Fugates’ lore, the blue skin is the headline. In clinical terms, the headline is oxygen delivery, because hemoglobin’s job is to move oxygen through the body, and methemoglobin cannot do that job in the normal way.

This is where the old stories of “blue blood” and “blue people” collide with the modern language of enzymes and genes. The same visible cue can signal very different underlying realities, and doctors had to learn which reality they faced.

What is known and what remains fuzzy in the origin story

The Fugates occupy an unusual space between local history and national folklore. Some elements repeat consistently across reputable summaries, while others shift depending on who is telling the story and how closely they stayed to records.

It is consistently reported that Martin Fugate and Elizabeth Smith carried the trait and that multiple children showed blue skin, placing the recessive inheritance pattern in the first generation that local accounts track.

It is less consistently documented that Martin himself was blue, or that he was an orphan from France, even though those details often appear in popular versions. A 2017 JAMA Dermatology note explicitly frames the “French orphan” claim as lore.

There are also discrepancies in the exact count of children attributed to the couple in different retellings. That kind of variation is common in multigenerational rural family stories that were passed along orally before they were written down.

The strongest through line is the demographic one. A small, close knit cluster of families lived for decades around the same creek valleys, and the same surnames show up in accounts because the same families married each other.

That does not require lurid detail to explain. It is the plain arithmetic of a recessive trait meeting a limited partner pool, and it is the same mechanism geneticists use to explain other founder effects and isolated cluster conditions.

The trait fades as the valley opens up

As Kentucky changed, the Fugates’ genetic story changed with it. Reporting describes how improved transportation, economic shifts, and migration widened the gene pool, lowering the odds that two carriers would pair and have visibly affected children.

In other words, the “blue people” did not vanish because medicine erased them. The visible trait became rarer because the community structure that amplified it loosened, and the recessive gene spread into larger populations where it seldom matched up.

That is why Benjy Stacy’s 1975 birth reads like an echo rather than a restart. It was a recognizable throwback to an older pattern, not proof that the older pattern still dominated the region.

Even in the modern era, a person can carry the gene and never know it. Medical references describe carriers and mild forms where symptoms are minimal, especially in certain inherited variants, which helps explain how the gene could travel quietly.

This is also where the internet era reshaped the story. Families once described as local curiosities became clickable, memed, and treated as folklore content, even though clinicians had already placed their condition within textbook medicine.

The myth survives because it has a visual hook. The medical reality survives because it has a paper trail, including mid century clinical research and later summaries that keep pointing back to the same basic diagnosis.

What the Blue Fugates story is really about

If you strip away the exaggeration, the Blue Fugates story becomes sharper, not duller. It shows how a rural community’s geography can shape its biology, and how biology can shape a community’s reputation for generations.

It also shows why “incest” is an imprecise summary. The evidence in reputable retellings centers on intermarriage within a small network, including cousin marriages, and the genetic consequences of that structure, not a documented ledger of explicit behavior.

The people at the center of the story lived ordinary lives under an extraordinary label. When a doctor finally met them in a clinic rather than on a rumor trail, the case turned from sideshow to study, and the color became a clue.

By the time reporters were writing about Benjy Stacy, the trait had already thinned out, which is why his blue skin reads as both a medical curiosity and a closing chapter in the popular narrative.

The legend began in a place that outsiders rarely visited, and it traveled because it felt too strange to be true. The real ending is quieter: a recessive gene, a handful of family trees, and a blue medicine that helped people blend back in.