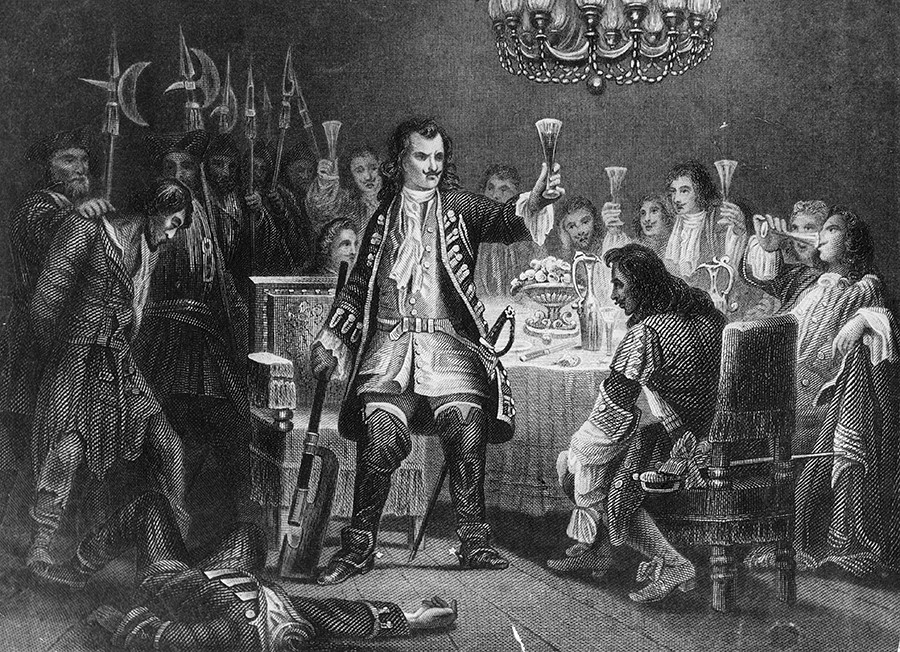

The scene looks like a bad joke. An elderly man in priest robes raises a huge cup of vodka, guests scream with laughter, and a Bible on the table hides flasks of alcohol inside its hollowed pages. At the centre of it all sits Tsar Peter Alekseevich, pleased with the chaos he has created.

This was not a one-off stunt. For years, Peter the Great ran a private drinking club with its own fake church hierarchy, laws, punishments, and festivals. It had a pope, bishops, processions, and a very clear commandment. Everyone drank, or everyone paid.

How Russia’s “Jolly Company” Became a Drunk Court Cult

The story began with a younger Peter and his so-called Jolly Company. This was a group of favourites, guards officers, nobles, and hangers-on who followed the young tsar through mock battles, nights in taverns, and rough practical jokes on the nobility.

They staged fake military campaigns outside Moscow. They dressed up as foreign officers and fought “battles” with wooden fortresses. Afterwards they dragged the same men back to feasts where barrels of drink waited and nobody was allowed to leave the table early.

Out of this Jolly Company, Peter started assigning titles that sound insane to a modern reader. One noble, Ivan Buturlin, played the enemy commander in a mock battle and never escaped the punishment. Peter started calling him “the Polish king” and the nickname stuck.

Another powerful figure, Fyodor Romodanovsky, became “Prince-Caesar.” Peter sometimes addressed him in letters as if he were the real sovereign, then appeared in person and treated him like a clown. This mixture of reward and humiliation became the basic rule of Peter’s circle.

The Night a Fake Pope Took Over

Around 1692, Peter went further and turned his drinking club into a parody church. He created what he called the All Joking All Drinking Synod of Fools and Jesters. It sounded playful, but it carried real weight, because membership depended on his favour.

He picked his old tutor, Nikita Zotov, to be the “Prince-Pope.” Zotov was known as pious, serious, and loyal. That made him the perfect target. Peter wrapped him in mock papal robes, gave him a staff, and placed him at the head of this fake religious body.

Peter himself took a lower church title, “proto-deacon,” and then wrote rules for the group. The basic idea was simple. They honoured Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, through constant drinking. That replaced any normal idea of holy behaviour inside this circle.

Being part of this Synod meant never refusing a cup. It also meant laughing at things ordinary believers treated as sacred. For people who wanted power and promotion, there was little choice. They drank, acted along, and let themselves become props in Peter’s performance.

When the Synod Crashed Real Church Holidays

The All Joking All Drinking Synod did not stay hidden behind palace doors. Peter aimed it straight at the official Russian church. The clash became clear in 1695 during the feast of Epiphany, one of the most important dates in the Orthodox calendar.

Traditionally, the tsar stood still and allowed holy water to be sprinkled on his head. It was a public sign that the ruler bowed to the church. Peter simply refused. Instead of submitting to the bishop, he used his fake Synod to run rival festivities.

He filled the holiday with sviatki style winter partying. This meant noise, crude jokes, and heavy drinking. Members dressed in costumes, chanted mock prayers, and honoured their Prince-Pope Zotov rather than the real patriarch. It was a direct insult to church authority.

Conservative observers were horrified. To them, Russia’s ruler was not only drinking heavily. He was mocking sacred rituals in front of the entire court and replacing them with a parody church that bowed to alcohol and to himself.

The Bible Filled with Vodka and the “Big Eagle” Cup

Inside the Synod, drinking had its own symbols and objects. One of the most famous stories is about a Bible with the pages cut out. In the empty space sat flasks filled with vodka. On the outside it looked like scripture. Inside it carried enough liquor to keep the table going.

The club had a special goblet called the “Big Eagle.” It was oversized and heavy. Latecomers, guests who annoyed the host, and anyone who tried to hold back were forced to drain it. Refusal was treated as an insult to Peter’s authority and to the group.

Meetings could start at midday and last until sunrise. Courtiers staggered out of the hall, sick, exhausted, and still expected to appear for official duties. If they wanted rank, land, or favour, they endured it and laughed along.

These rules turned alcohol into a test of loyalty. Peter could watch who carried on drinking, who broke down, and who tried to evade the game. The Synod looked like a joke. In practice it acted like an informal court inspection.

Public Processions That Turned Moscow into a Stage

The club did not limit itself to indoor feasts. Peter liked public processions. Members of the Synod dressed in strange costumes and rode through Moscow in long parades that mixed religious imagery, carnival behaviour, and raw mockery of normal order.

In one recorded entry into the city, the group passed through a triumphal arch decorated with the classical gods Hercules and Mars. Zotov and other favourites rode at the front in decorated carriages. Peter followed in a lower “church” role that he had invented for himself.

During winter festivals, the Synod moved through the streets singing songs, collecting money, and acting like an official holiday troupe. Wealthy households were pressured to donate. Refusing meant attracting unwanted attention and possible trouble later.

These processions flipped the social ladder. People who normally stood in judgment, such as nobles and clergy, suddenly became targets of laughter. At the same time, everyone understood that the real power behind the joke was the tsar himself.

The Dwarf Wedding That Copied a Royal Ceremony

In 1710, Peter staged a dwarf wedding that many historians place in the same universe as the All Joking All Drinking Synod. It followed shortly after a grand royal wedding and copied its structure, only with dwarfs as the “royal” couple.

The groom was Iakim Volkov, one of Peter’s court dwarfs. The bride was a dwarf woman chosen for him. They sat in the centre of the hall at small tables and tried to move through a full court ceremony while taller courtiers drank, stared, and cracked jokes.

Eyewitnesses wrote about drunk guests, dwarf fights, falls, and clumsy dancing. It was entertainment for the tsar and his friends. For the participants, it was a reminder that their lives and bodies could be turned into a spectacle whenever Peter liked.

This was not the only time dwarfs served as props. At other feasts, Peter had them hidden inside giant pies so that they burst out when the crust was cut. Every surprise reinforced the same message. The court existed to perform for its ruler.

Zotov’s Grotesque Marriage, Or How to Turn a Tutor into a Clown

The peak of this mocking culture came with the wedding of Nikita Zotov, the Prince-Pope of the Drunken Synod. By then he was aged and long past his youth. Peter insisted he marry a widow who was decades younger.

Preparations took months. The court planned invitations, costumes, and roles with the same care as a diplomatic event. Except here, the goal was humiliation. Guests came masked. Many were chosen because of visible disabilities, physical quirks, or speech problems.

Messengers with stammers delivered the wedding notices on purpose, providing comedy before the event even began. A so-called priest, described as blind and extremely old, led parts of the ceremony. Musicians and carolers walked the streets collecting money in character.

The wedding worked as public theatre. It mocked both the idea of a holy union and the man who once taught Peter. At the same time, it forced everyone present to accept the new rules. Under this tsar, even an honoured tutor could become a joke.

When the Party Turned Deadly

The Synod did real damage to some of its members. One grim example is the death of Yakov Turgenev, a jester and officer in Peter’s circle. Accounts say he died in his forties during a “joke” at one of the club’s gatherings.

The details are sparse, but the pattern is clear. Men drank beyond safety to keep up with expectations. Refusing to play along meant exclusion. Staying in the game meant physical risk. Turgenev’s death sits on that line between entertainment and cruelty.

Peter did not halt the culture after this. The games continued, the rituals stayed in place, and the Synod kept meeting and drinking. For the ruler, the system worked. It gave him a tool to test people and break resistance without formal punishment.

The Same Men at the Party and the Execution Ground

The faces at these feasts did not disappear when serious matters arose. The same Jolly Company officers and Synod members followed Peter into real wars, diplomatic missions, and brutal acts of state violence.

They travelled with him on the Grand Embassy to Europe, where their heavy drinking and sudden antics alarmed more formal Western courts. They were present at campaigns such as Azov, where Peter used their loyalty in real battles instead of staged ones.

Some of these men stood beside him when he returned to crush the Streltsy rebellion in 1698. Contemporary reports describe Peter personally questioning, torturing, and supervising executions of the rebel guards. His inner circle, trained to obey him in everything, helped carry it out.

In this light, the All Joking All Drinking Synod looks less like a harmless party club and more like a training ground. It prepared elites to accept humiliation, public performance, and absolute control in private so that they would not resist in public.

For outsiders, the club appeared as a rowdy drinking society that mocked priests and staged dwarf weddings. For the people inside it, it was the place where careers depended on an empty cup, a forced laugh, and a ruler who never stopped watching.