Nellie Bly took an assignment that required her to surrender control of her own life. She planned to enter New York’s public asylum as a patient and stay long enough to learn what daily treatment looked like.

Her method depended on a blunt fact about power and belief. If strangers could be convinced she was “insane,” officials would move her through courts and hospitals with little resistance.

She began in a boardinghouse for women, where her behavior turned into a public test. She stayed awake, stared, spoke oddly, and let the room decide what she was.

The other residents watched her with growing fear and irritation. Once they stopped seeing her as a person, calling the police felt like a normal next step.

Police took custody and treated her like something that needed processing. Questions came fast, answers were ignored, and the goal became a clean transfer to the next authority.

A judge heard brief statements and leaned on quick impressions. The hearing offered little patience for nuance, and it showed how a short scene could decide months or years.

Doctors asked a few questions and reached firm conclusions with little examination. Their certainty turned the act into paperwork, and the paperwork turned the act into confinement.

At Bellevue Hospital, the first shock came from the tone of the ward. Staff gave orders sharply, spoke to women as if they were dirt, and acted irritated by any request.

Punishment started with language and posture, then moved into hands. A patient who hesitated or questioned a rule could be shoved, yanked, or threatened into compliance.

Food arrived as small portions that felt careless and mean. Women ate quickly because hunger stayed constant, and complaining only brought ridicule or retaliation.

Sitting became a rule enforced like discipline. Patients were made to stay on benches for long stretches, and any movement could bring scolding or physical correction.

The ward held women who seemed frightened, sick, confused, or exhausted rather than delusional. Once a woman carried the label, every reaction became proof that she deserved it.

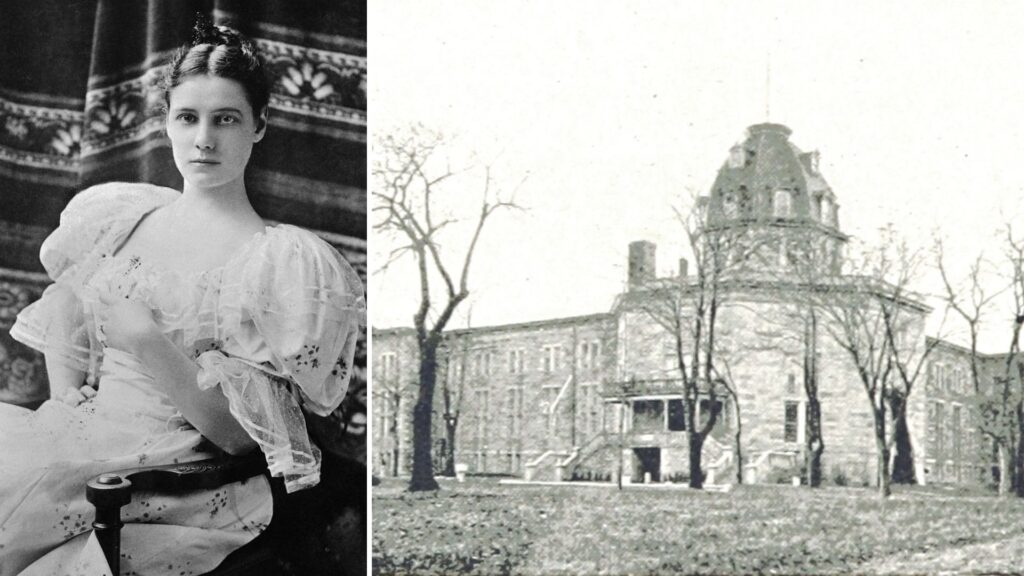

The transfer to Blackwell’s Island moved her farther from public view. The trip felt simple for staff and terrifying for patients, because water and distance made escape feel impossible.

Intake on the island stripped away privacy and ordinary dignity. Clothing changed, personal items disappeared, and a woman’s body became something staff managed without asking permission.

Cold was part of daily life there, not a rare discomfort. Thin clothing, weak heat, and long idle hours left women shivering while staff treated their pain as noise.

One of the harshest controls involved bathing under force. The water was cold, the handling was rough, and refusal was met with strength rather than care.

If a woman resisted, attendants could hold her down and push her through it. The event was framed as cleanliness, yet it functioned like punishment for having a body.

After the bath came the bench again, and then more bench. Women were ordered to sit straight, stay quiet, and keep their eyes forward as if stillness itself proved obedience.

Silence was demanded, but the building was never truly quiet. Crying, arguments, and shouted commands filled the air, and the sound made sleep and calm hard to reach.

Verbal abuse worked as a constant pressure that wore people down. Staff mocked accents, laughed at fear, and called women names with the ease of habit.

Physical violence appeared as sudden “corrections” for small acts. A slow step, a wrong look, or a whispered sentence could bring a slap, a shake, or a hard grip.

Threats kept the ward under control when fists were not needed. Nurses promised worse treatment later, promised harsher wards, and promised payback when no outsider would see.

Doctors passed through quickly, then vanished back into distance and comfort. Their short visits left daily power with attendants, and attendants enforced control through fear and routine.

The trap for a patient trying to prove sanity was simple and brutal. Calm arguments were dismissed as trickery, and tears were used as proof of instability.

Speaking up carried a price, because staff treated it as disorder. A complaint could lead to humiliation in front of others, or to a private punishment away from witnesses.

Night offered little protection from cruelty or neglect. Bedding felt inadequate, the air stayed cold, and noise kept bodies alert even when exhaustion begged for sleep.

Lack of rest changed how people behaved, and staff used that change against them. A tired mind stumbles, and any stumble became a reason to tighten control.

Privacy hardly existed, even during sickness or personal care. Constant exposure worked like punishment, because it reduced shame’s protection and made women feel owned.

Language barriers turned into another weapon against immigrants. Confusion was interpreted as madness, and the inability to argue clearly left women trapped in silence.

Rules were enforced without explanation, then used to justify punishment. A woman could break a rule she never understood, and the response would still be swift and harsh.

Food on the island remained a steady source of suffering. Meals could be stale or poorly prepared, and patients were forced to swallow it quickly while staff policed every complaint.

Hunger did more than hurt the stomach. It drained energy, sharpened anger, and made women easier to control because weakness reduces the ability to resist.

Forced sitting and forced silence worked together as a slow grind. With nothing to do and nowhere to go, time itself became a punishment administered by the clock.

Some women were clearly ill in body, yet received little real care. The label of madness covered fevers, pain, and weakness, and neglect became an everyday practice.

Labor and chores could be used as discipline rather than help. Scrubbing and cleaning came with scolding and threats, and imperfect work could bring sharper treatment.

Group punishment also appeared, tightening the whole ward after one person spoke out. It reduced trust between patients, because everyone feared being blamed for another woman’s mistake.

Staff behavior often shifted when outsiders appeared. Politeness surfaced briefly in front of visitors, then faded once the door closed and attention moved away.

That switch mattered because it proved the cruelty was a choice. People who can perform kindness for witnesses can also choose to treat patients decently when nobody is watching.

Fear shaped patient behavior into something staff then pointed to as illness. Women learned to keep eyes down, faces blank, and voices low to avoid becoming a target.

Some stopped speaking almost entirely, because speech invited danger. The ward could turn ordinary grief and frustration into a survival lesson: stay quiet or pay.

When women begged to leave, staff treated begging as proof of madness. When women stopped begging, staff treated silence as stubbornness and punished that too.

The cold bath remained one of the most dreaded events because it joined humiliation and force. It also showed how pain could be delivered under the label of “care.”

A patient’s body was handled like a thing to be moved, washed, seated, and restrained. The lack of consent was constant, and the constantness was the point.

The book shows how little evidence was needed to keep someone locked away. Once the doors closed, a patient’s words lost value, because staff treated words as symptoms.

Release depended on outside power rather than careful review from inside. Without contacts or money, many women had no lever to pull, even if they were fully sane.

After ten days, her newspaper arranged her exit, and the change in treatment was immediate. Officials who barked orders inside now used polite voices in public settings.

The reporting sparked an investigation by a grand jury and forced officials to answer questions. Testimony turned private cruelty into public record, and public record made denial harder.

Money for care increased and reforms were discussed, because attention brings pressure. Yet the basic scenes remained easy to imagine continuing once attention moved away.

On the island, women still faced the same bench hours and the same cold rooms. They still watched the bath line form, still tasted the same thin meals, and still learned silence as safety.