In the first weeks after Andrew’s disappearance, reports started landing on detectives’ desks. People thought they had seen a slight teenager with dark hair in London, usually alone, often quiet, sometimes with a rucksack that looked familiar.

One report placed him at a Pizza Hut on Oxford Street on the day he arrived, around an hour’s walk from King’s Cross. Staff remembered a boy who matched his description eating alone, polite, self contained, paying in cash, then leaving.

Other reports followed. Someone believed they saw him sleeping on a park bench in Southwark a few days later. Another person said a boy who looked like Andrew stepped off a local train at Mortlake, near Richmond, and walked away up Sheen Lane.

By the first anniversary, there were more than one hundred possible sightings recorded across Britain, including dozens in London and several in Brighton. Some came with detailed descriptions, others were only brief impressions of a familiar face seen in passing.

Kevin and Glenys felt two or three early sightings sounded plausible, especially the Oxford Street account. The way witnesses described his speech and behaviour fitted what they knew of their son. They believed that lead should have been treated more seriously.

Sorting real clues from noise

Detectives had to decide which sightings justified active follow up. They visited restaurants, checked CCTV where it still existed, spoke to staff and regular customers. In many locations, camera footage had already been overwritten or was too poor to identify individuals.

Statements sometimes conflicted on basic details like height, clothing or hair length. London also held many teenagers who matched Andrew’s general description. Without a distinctive ear clearly visible or a named contact, none of the sightings reached the level of confirmation.

The family watched that process with growing frustration. Each call might have marked the moment Andrew crossed someone’s path. Each closed report settled back into the mass of unverified information, one more line in a file that still lacked a clear route.

The digital investigation that went nowhere

Police took away the family computer, Andrew’s games consoles and any storage devices they could find. Technicians went through browser histories, files and email accounts, looking for contact with strangers, plans for a trip or messages that hinted at distress.

They checked school and library computers he might have used, and they checked his PSP with the manufacturer to see whether it had ever connected to online services or logged into messaging platforms. Nothing pointed to a hidden digital life or secret arrangements.

Andrew did not use social media in the way many teenagers did, and he did not have a laptop of his own. Police found no evidence that he had been groomed online or lured into a plan through chat rooms or forums.

That absence created its own problem. Many missing teenager cases leave text messages, arguments on social media, old chat logs or search histories. Andrew’s case lacked those entries. Investigators could not say whether he was keeping secrets or simply living a quieter digital life.

What might have pulled him to London

Families in these situations end up building their own theories. Kevin and Glenys considered that Andrew might have copied his sister’s earlier experience, when she had gone to London at fourteen to hand out CVs for work experience on the Strand.

They knew he liked London’s museums and attractions, and they wondered whether he had wanted a day in the capital that belonged entirely to him. A trip without parental oversight, where he could walk, explore, buy merchandise and visit places that interested him.

Others suggested he might have travelled for a specific event, perhaps a gig or gaming launch, or to meet someone he had spoken to through less obvious channels. Nothing in his room or devices clearly supported any of those ideas.

Police also explored darker possibilities, including self harm, accidental death in an unobserved place or contact with predatory adults. Without a body, a confession or physical evidence, those remained as theoretical as the gentler explanations involving independence or curiosity.

Early pressure and strange official ideas

In later interviews, Kevin described the early investigation as both necessary and deeply painful. Detectives looked closely at the family, as procedure required. He understood the process in principle but found the tone and some suggestions extremely difficult to absorb.

He recalled being treated as a potential suspect in his own son’s disappearance, questioned about whether he might have harmed Andrew and hidden the truth. That period left lasting scars, including long term depression and a suicide attempt, which he has since spoken about publicly.

Kevin also revealed that at one point officers suggested Andrew could have left to join an extremist group abroad, after seeing he had borrowed books about Islam from the library for a school project. The family regarded that idea as implausible and disturbing.

Alongside that, Kevin criticised delays in securing CCTV from key locations in London. By the time some requests travelled through the system, recordings had already been taped over, removing chances to track Andrew on streets or Underground platforms near King’s Cross.

Expanding the search beyond first guesses

As months passed, the search widened geographically and technically. Investigators considered whether Andrew might have travelled onwards from London to coastal towns like Brighton, which featured in several unconfirmed sightings, or to other cities linked to reports.

In 2011, sonar equipment was used to search sections of the River Thames, based on the idea that an accident or self harm incident might have gone unseen in the water. The operation did not find anything connected to Andrew’s disappearance.

The case also moved through national systems. The National Crime Agency took an interest, and Andrew’s DNA and dental information were kept available for checks against unidentified remains and unknown patients. Those checks have continued over the years without producing a match.

Public appeals and the work of memory

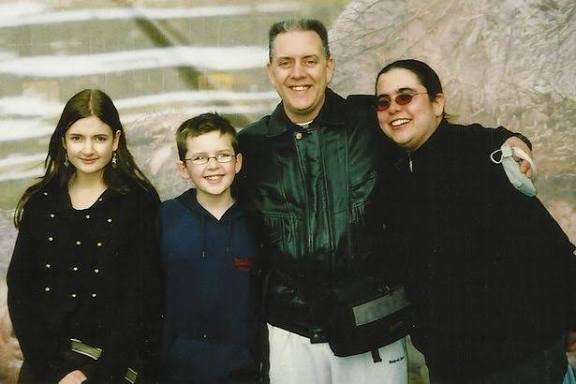

While investigators followed reports and technical leads, the family worked with the charity Missing People and media outlets to keep Andrew’s case visible. Posters went up, appeals appeared in television segments and new photographs were prepared when he reached each new age milestone.

Specialists created age progression images to show how he might look as a young adult. In 2019, South Yorkshire Police released a picture that removed his glasses, because there was a chance he had stopped wearing them or switched to contact lenses.

Further updates followed in 2020 and beyond, with new images supplied for awareness campaigns and social media appeals. Each picture tried to bridge the gap between a fourteen year old schoolboy in a Slipknot T shirt and a man in his twenties or thirties.

In 2025, Kevin wrote about this process for Missing People, explaining how public remembrance can feel both supportive and exhausting. He described memory as a kind of duty, something he carries so that Andrew does not slip into statistics or background noise.

The 2021 arrests that looked like a turning point

Fourteen years after Andrew left home, there was a major development. In December 2021, South Yorkshire Police arrested two men in London, aged thirty eight and forty five, on suspicion of kidnapping and human trafficking in connection with the case.

Reports at the time stated that one of the men was also questioned about offences relating to indecent images of children. Officers searched property, seized digital devices and carried out detailed forensic work. For the first time in years, the family felt real hope for answers.

The investigation lasted many months. Detectives reviewed communications, travel histories and any possible link between the suspects and a fourteen year old who travelled alone to London in 2007. The work ran in the background while public appeals stayed relatively quiet.

In September 2023, police announced that both men had been released without charge and eliminated from the inquiry. Whatever had prompted the original tip, investigators no longer believed either man had anything to do with Andrew’s disappearance.

For the family, that outcome meant another intense rise and fall. Hope that someone might face questions in court gave way to the familiar absence of clear direction. The case returned to its original state, an open file with many paths and no firm answers.

A case that resists simple stories

People often try to place the case into a category. Runaway, stranger abduction, trafficking, radicalisation, accident, carefully planned disappearance. Each label has been suggested at some point. Each one struggles against basic facts that do not fit cleanly.

Andrew had withdrawn money and chosen a single ticket, so he seemed to expect at least some time away. He went to a city he did not know well, with no phone, no spare clothes, and no obvious plan that survived on paper or screen.

If he met someone at King’s Cross or nearby, that person has never come forward. If he continued alone, he did so in a way that left no clear trace in hostels, hospitals, employment records or police encounters under his own name.

The family has always considered the possibility that Andrew might still be alive somewhere, perhaps living under another identity, perhaps unaware that people still search for him. They hold that thought alongside the knowledge that many missing teenager cases end in tragedy.

Living with an unanswered day

Nearly eighteen years on, Andrew’s room remains a reference point rather than a museum. The family has allowed some natural change, but key items stay in place. The PSP charger, the books, the clothes he left behind all mark a life paused mid sentence.

Kevin has written about the strain of waiting, of adjusting to a form of loss that lacks funerals or anniversaries. Hope and acceptance move in cycles. Some days are spent writing appeals or giving interviews, other days are quieter and turned inward.

The case remains open with South Yorkshire Police. New information is still invited, and age progression images continue to circulate in news articles, charity campaigns and on social media. Each new release asks the same underlying question in a slightly different visual language.

One recent image, created when Andrew would have been in his late twenties, shows a man with similar bone structure, short hair and the same distinctive fold in his right ear. It is built from measurements and modelling rather than photographs of his actual adult face.

Somewhere in that gap between a fourteen year old on a station concourse and a digitally aged adult lies everything people do not know. The train journey is documented, the arrival is documented, the walk out of frame is documented. The rest is still missing.