In Madison, Wisconsin, a graduate student slid a pyramid-shaped lid into place above a stainless-steel trough. Inside, a young rhesus macaque scrabbled at the sloped walls, looking for an edge, a seam, anything that could turn metal into a foothold. The surface offered none.

The chamber narrowed toward a rounded bottom. A wire-mesh floor sat just above a drain so waste could drop through. Food and water waited in mounted holders. The design gave the animal a single option: down.

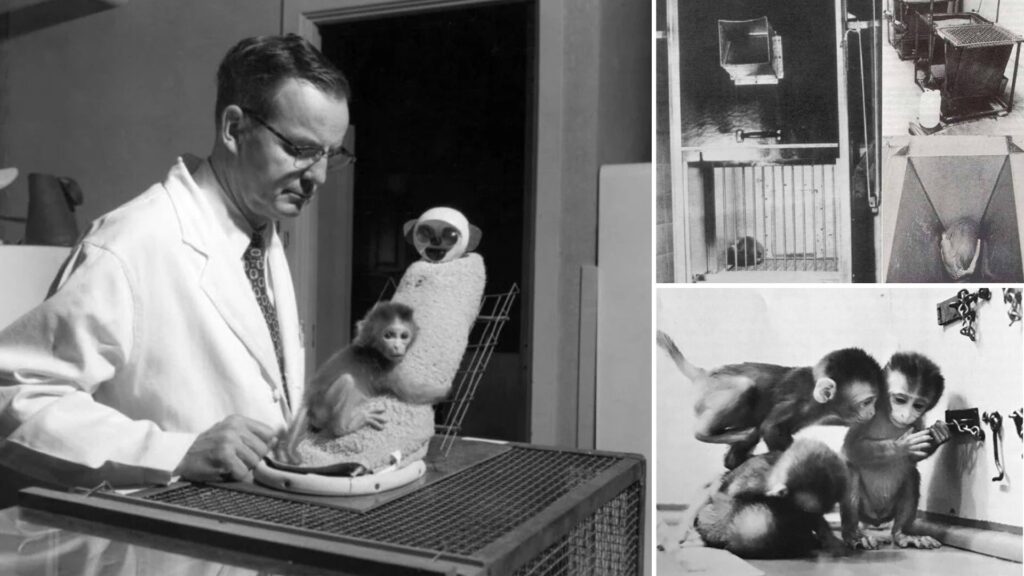

Harry Harlow, the University of Wisconsin psychologist who ran the primate lab, insisted on a name that sounded like a place, not a device. He called it the Pit of Despair. His student Stephen Suomi used a plainer label in print: the vertical chamber.

Harlow built the pit for a specific purpose. He wanted to create, on schedule, a state that resembled human depression, then test whether anything could pull a damaged social animal back into ordinary life. The work collided with public sensibilities, drew protests, split colleagues, and helped push research institutions toward tighter oversight.

Harlow arrived at the University of Wisconsin in 1930, fresh from a Stanford doctorate and eager for a laboratory. He found little space and less patience for his plans, so he improvised, first working with primates at the local zoo and then carving out a home for monkeys near campus.

He made his early name on cognition. He built apparatuses that forced animals to solve problems, remember locations, and form “learning sets.” Students cycled through his lab and his tests, producing dissertations and a steady stream of papers that treated rhesus macaques as complex, strategic minds.

After the Second World War, Harlow turned from puzzles to relationships. He watched infants cling, vocalize, and panic when separated, and he began asking questions that psychologists of his era often kept at arm’s length. He used the word “love” when many colleagues preferred colder terms.

In the late 1950s, Harlow’s lab introduced the experiment that made his reputation with the public: the cloth mother and the wire mother. Infant monkeys clung to the soft surrogate even when the feeding bottle sat on the bare-metal frame. Harlow told audiences that warmth and contact could outweigh milk.

Fame followed. Photographs of small monkeys gripping cloth forms traveled far beyond academic journals. Harlow collected major honors, and his lab expanded into a machine that trained graduate students and generated results that shaped developmental psychology for decades.

The work also carried a problem Harlow could not ignore. Some monkeys raised with surrogates grew into adults with severe social deficits. Harlow and his team watched animals freeze in groups, mishandle courtship, and fail at basic monkey life. The lab responded the way it always had: by designing harsher tests.

By the mid-1960s, the University of Wisconsin joined Harlow’s primate laboratory with the Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center, part of a national system backed by federal money. Harlow became director of the merged center. Grants from the National Institutes of Health kept animals, staff, and buildings running.

Harlow’s personal life tightened around illness. His wife, Margaret “Peggy” Harlow, faced breast cancer. In 1968, Harlow fell into a major depression and entered the Mayo Clinic for psychiatric treatment, staying nearly two months. He wrote obsessively during that period, treating his own mind like a subject.

He submitted to electroconvulsive therapy, writing later about his doubts and his compliance. He judged the evidence as thin and the studies as sloppy, then admitted the treatment provided transient relief. He left the clinic still consumed by the felt reality of depression and by the idea that science owed it a better answer.

Harlow had already begun moving in that direction. He had run social deprivation studies for years, and he had started preparing talks on depression in “subhuman animals” before his hospitalization. In 1969, the center added a clinical psychiatrist, William McKinney, who brought a clinician’s vocabulary into a primate laboratory.

Harlow wanted a model that could answer practical questions. He aimed at bonds: what kinds of attachments, when broken, produced collapse; what kinds of separation experiences carried the strongest effects; how age changed the response; what reunion could repair, and when.

The lab tried smaller steps first. Harlow built “evil” surrogate mothers that could shake, blast air, or present spikes, briefly disturbing infants. The effects faded. He pushed harder on isolation, separating monkeys from mothers, then from peers, then from any other monkey contact at all.

Engineers and students built cages that allowed repetitive separation by sliding in screens. Harlow called one version a “quad cage.” It could work, but it demanded time. Harlow wanted speed. He wanted something that could take a previously social animal and break it quickly.

Harlow and Suomi designed the vertical chamber to make escape attempts pointless. The sloped sides forced an animal back to the rounded bottom. The mesh floor prevented the comfort of stable footing. The pyramid top discouraged hanging from the rim. The chamber left the monkey alive, fed, and alone.

The lab used monkeys old enough to have already formed bonds—juveniles and young animals that had known mothers and peers. Harlow wanted the fall from normal social life, not the emptiness of an animal that had never learned what company felt like.

Suomi described a typical confinement lasting about 30 days, though the lab also used longer periods in related isolation work. The first hours often involved frantic movement and repeated climbing attempts. The chamber turned those attempts into a loop: up, slide, down.

Within days, the activity dropped. The animal’s body language changed into stillness and curled posture at the bottom. Harlow and Suomi wrote that they did not ask monkeys whether they felt helpless or hopeless, but they treated posture and inactivity as behavioral markers of “giving up.”

Harlow gave the chamber its theatrical name on purpose. He liked language that provoked, and colleagues urged him to choose a blander label that would travel better outside the lab. A former student, Gene Sackett, later recalled Harlow first wanted “dungeon of despair,” then settled on “pit.”

Harlow did not stop at silence. The lab built a companion device, the “tunnel of terror,” designed to intensify fear. One described version involved a tunnel where a moving toy could approach the monkey. The apparatuses turned mood and threat into something the lab could schedule.

The work met a country that was beginning to argue, louder, about laboratory animals. The Laboratory Animal Welfare Act had passed in 1966, and the broader Animal Welfare Act evolved through amendments. Protesters wrote Harlow directly. Activists organized. Journalists paid attention.

Harlow answered critics with a mix of personal grief and institutional certainty. In a 1971 letter responding to complaints, he invoked his wife’s cancer and the suffering he associated with depression. He argued that long-term goals of alleviating human suffering justified the use of nonhuman animals, and he insisted his lab cared for animals humanely by the standards of the time.

Discomfort also came from inside the scientific world. Some colleagues questioned the necessity of the vertical chamber. Suomi and John Gluck later distanced themselves from that style of deprivation work. Harlow stayed on his chosen track, convinced that the parallels between monkey development and human development made the methods defensible.

Harlow still wanted something more than a model of collapse. He wanted a way back. He tested drug approaches and considered shock therapy in animals, then kept circling toward the tool he understood best: social contact. He believed relationships could damage a mind, and relationships could repair it.

The lab began pairing depressed monkeys with “therapist” monkeys: socially healthy animals, younger than the withdrawn ones. Harlow chose younger partners for a reason. He had seen same-age peers behave aggressively toward isolation-reared monkeys, and he wanted a safer social bridge.

Handlers brought the therapist monkeys in for hours on most days, then separated them again. The young animals approached the older depressed monkeys and clung to them. The depressed animals initially stayed curled and unresponsive, then began tolerating contact, then began returning it.

Over time, the lab saw play emerge. The therapist monkeys initiated rudimentary games. The depressed monkeys began moving again, then participating, then initiating. The changes did not erase everything isolation had done, but they gave Harlow what he had chased: an intervention with observable effects.

Harlow also carried pessimism alongside those results. In earlier letters, he had written that deprivation in the first months of life could destroy a monkey as a social animal “forever,” then admitted later that rehabilitation succeeded more than he expected. He allowed himself to be corrected, but he did not soften his methods.

Harlow stepped down from leadership roles as age and institutional rules caught up with him, but the legacy of the pit outlived his title. He died in 1981. The devices and their names continued to circulate, turning into shorthand for a kind of scientific extremity that even many researchers did not want to defend publicly.

In December 1985, Congress signed amendments to the Animal Welfare Act that demanded more from registered research facilities. The law required exercise opportunities for dogs and psychological well-being provisions for primates, pushing institutions to treat social needs as a compliance obligation, not a nicety.

Universities responded by building layers of review and documentation into their animal programs, and by formalizing committees that judged pain, distress, and alternatives before experiments began. The new rules did not erase the past experiments, but they changed the operating environment that had made them possible.

Harlow never saw those amendments take effect. He left behind photographs of soft surrogate mothers and a steel chamber with a theatrical name, both built from the same conviction that a laboratory could translate feeling into apparatus and apparatus back into something like cure.

Isolation as experiment has a long history. King James IV of Scotland once marooned a mute woman and two infants on an island to observe what he believed would reveal humanity’s original language.

Sources

- “Harry Harlow’s pit of despair: Depression in monkeys and men,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences (2022)

- PBS, “A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries: Harry Harlow”

- National Institutes of Health, PubMed entries for Suomi & Harlow (1972) and McKinney, Suomi & Harlow (1972)

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library: Animal Welfare Act overview and amendments

- Animal Welfare Institute: Animal Welfare Act legislative timeline and 1985 amendments summary

- The New Yorker magazine feature referencing Harlow and the “pit of despair” in the context of modern primate research (2025)

- “Harry Harlow: From the Other Side of the Desk,” The Journal of Medical Humanities (2008)

- University of Wisconsin: Madison digital collections material referencing Harlow’s role and primate laboratory history

- Wikipedia entries for background facts on Harry Harlow, Margaret Kuenne Harlow, and the Pit of Despair