In the early 1970s, San Francisco was already on edge. There were radical groups, famous killers, and civil rights protests making the news almost daily. People talked about groups like the Black Liberation Army, the Panthers, and the Symbionese Liberation Army. Many believed the city was just one big incident away from serious trouble.

It started as small rumors in bars and coffee shops. Some folks brushed them off as wild gossip. Others warned that San Francisco was like a pile of dry leaves—just one spark away from catching fire. Sadly, reality proved even darker than anyone guessed.

At first, the crimes seemed random: people attacked on the street, strange kidnappings, and bodies turning up in alleys. The police found a few clues—.32-caliber bullets, up-close shootings, and no clear motive. Slowly, a pattern came into focus, pointing to a sinister kind of fanaticism.

Fear spread through the city as more victims showed up. According to SFGate, those who lived through that time still remember how every stranger’s glance felt threatening. People started locking their doors more often. Nights out became rare. It was like fear itself ran the city.

Anyone new to San Francisco must have wondered how a place famous for art and forward thinking had become so unsafe. Many blamed the wild social changes of the time. But the truth ran far deeper than typical political unrest.

By late 1973, the violence sped up. Almost every week, someone was attacked while living an ordinary day. The unpredictability was the scariest part. There were racial overtones, too, which made things even more tense. Quietly, people admitted that San Francisco felt like a dark maze. One wrong turn could mean danger.

A Powder Keg Ready to Blow

Before the killings became front-page news, the city had already faced horrors like the Zodiac Killer. But the new spree felt even worse—almost organized. It wasn’t just one person acting alone; it looked like a group seeking revenge.

Regular people were targeted: a couple on an evening stroll, a shop owner behind the counter, or an older man collecting trash to earn a few dollars. Some victims died immediately, riddled with bullets. Others survived brutal attacks that shocked experienced detectives. And the police suspected more than one shooter.

Still, there was a common thread. The same caliber bullets appeared again and again. Many victims were white, pointing to a possible racial motive. Investigators began hearing about a group calling itself the “Death Angels.” Wikipedia notes that these members believed random violence would spark a huge racial conflict.

One terrifying example happened on October 20, 1973. Richard Hague and his wife, Quita, were kidnapped. She was found almost decapitated by railroad tracks. Richard, injured and bleeding, managed to escape. Just days before, three boys had nearly been snatched in a similar way. The killers struck like lightning, leaving hardly any evidence.

Sometimes, there were multiple attacks in a single night. Victims rarely had time to react. Some were shot in the back. Others were cornered in everyday places like parking lots. The city’s lively culture started to fade, replaced by locked doors and shuttered windows.

A Trail of Terror

For months, police tried to figure out who was behind these crimes. San Francisco had several radical groups, but the Death Angels stood out for their extreme violence. Some people thought they wanted a race war that would tear the city apart.

Things got worse on January 28, 1974, when five shootings took place in just a few hours. A 69-year-old man going through garbage and another person doing laundry both ended up dead. Investigators linked these killings to the same .32-caliber gun.

Reporters called these crimes the “Zebra murders,” named after the special Z police radio channel assigned to the case. The killers seemed to vanish into thin air, leaving hardly any witnesses who could clearly identify them.

There was also talk that an extremist wing of the Nation of Islam might be involved. Many leaders publicly denied any connection, calling the suspects a rogue group. Still, the possible link to local temples couldn’t be dismissed. As a result, some neighborhoods considered forming patrol squads. By then, the fear was so great that people felt they had to take safety into their own hands.

Meanwhile, the killers kept at it. They sometimes kidnapped people, took them to secluded places, and left the bodies in pieces. Veteran officers described crime scenes so gruesome that even they were shocked. The randomness of it all meant anyone could be a target: a teenage hitchhiker, an elderly man on a short walk—no one felt safe.

Fear on Every Corner

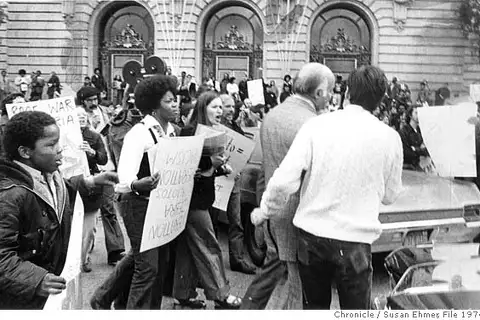

As the death toll rose, city leaders decided to crack down. They launched “Operation Zebra,” which meant stopping anyone who fit the vague description of the killers. In practice, this meant a lot of Black men were pulled aside. Checkpoints popped up across the city. Officers demanded IDs, often without much cause, leaving many people feeling angry and singled out.

Civil rights groups sued, saying Operation Zebra was racist and unconstitutional. City officials insisted it was needed to protect lives, but the sweeps didn’t produce clear results. Eventually, the courts ruled that these blanket searches were illegal. By then, though, entire communities were furious at the police.

In the middle of this, a special task force was quietly gathering real leads. A major breakthrough came when a man named Anthony Harris, who was close to the group, gave inside information about who was involved and what weapons they used. Police began following suspects day and night, hoping to catch them before they struck again.

Finally, arrests were made. Men like J.C. Simon, Larry Green, and Manuel Moore were named as key figures. But even after the arrests, the city worried there might be more killers out there, ready to retaliate.

Operation Zebra: A City at Odds with Itself

The arrests offered some relief, but Operation Zebra had already done its damage. Many Black residents felt they had been treated as suspects just because of their race. Families of victims, on the other hand, demanded harsh punishment for the murderers.

Prosecutors pieced together a strong case. They linked the same .32-caliber bullets to different crime scenes. They brought in witnesses who claimed the suspects talked about earning “points” for each murder, like a grim scoreboard. The defense tried to question these testimonies, but the mountain of evidence—including items found in the suspects’ homes—was too large to ignore.

Tensions were high in court, mirroring the city’s unrest. Some people wondered if San Francisco could ever fully recover from so many random killings. Others felt they had to look at deeper issues: why did these men grow so hateful?

As the trials moved forward, several suspects were convicted and sent to prison for life. Yet the harm done to local trust didn’t simply vanish. People argued about the thin line between public safety and civil rights. That debate went on for years.

Catching the Death Angels

During the investigation, detectives discovered that the suspects believed they were fighting a holy war. Some blamed their twisted ideas on religion. Others said it was rooted in raw anger over race. Either way, the result was a long series of murders that left dozens of people dead or injured.

Police found evidence that the killers tracked victims like they were adding tallies to a scoreboard. Their methods weren’t just lethal; they aimed to terrify. Dismemberment and near-beheadings were especially horrifying. It didn’t matter who you were: young, old, local, visitor—everyone felt at risk.

The city, known for openness, suddenly appeared to hide dark corners where hate could grow. Ironically, some of the police officers trying to solve these crimes were also dealing with discrimination inside the force, showing just how tangled the situation was.

A lot of regular activists felt overshadowed, too. They wanted fair treatment for everyone, but they worried that people would see all social movements through the lens of these killers’ violence. In the end, it seemed these killers twisted honest calls for progress into a reason for murder.

When the dust finally settled, only a handful of men had caused all this devastation. They abused a tense moment in history to justify their actions. Their arrests brought some closure, but left the city shaken.

Lingering Shadows

Decades later, the Zebra murders still cast a shadow over San Francisco’s history. Many locals prefer to focus on the city’s creative vibe and welcoming spirit. But the scars from that period never fully faded. Loved ones of the victims were left with empty chairs at dinner tables and memories of sudden, violent loss.

Some survivors, like future mayor Art Agnos (who was shot during this spree), carried both physical and emotional wounds. The police, heavily criticized for Operation Zebra, had to rethink strategies. Over time, the city tried to build better relationships between officers and the community. Even so, critics say the root problems—like inequality and hostility—haven’t vanished.

The Zebra murders also showed how hard it is to spot dangerous groups before they unleash terror. On the surface, these suspects led normal lives. No one realized they were planning to attack random strangers. Only when bodies began to pile up did everyone see the danger.

Today, many people don’t know much about the Zebra murders. Other crimes, like the Zodiac Killer, seem to get more attention. Yet for those who lived through it, that era was a time of nightly fear and early closing hours. It’s a reminder that life can spiral out of control when hate drives the actions of even a small group.