In March 1984, Japan’s confectionery industry became the center of a crime story that stretched for sixteen months and still remains unresolved. It began with an abduction in Hyogo Prefecture and spiraled into threats, poison scares, and one of the largest police operations in modern Japanese history.

The case became known as The Monster With 21 Faces — a name taken directly from the taunting letters that flooded newspaper offices and police mailrooms, each signed with the same mocking alias.

On March 18, 1984, two masked men entered the Nishinomiya home of Ezaki Glico president Katsuhisa Ezaki. They had used a key stolen from a neighboring residence, tied up his family, and forced the executive from his bath.

He was taken to a warehouse north of Osaka and guarded in shifts. Food was left nearby; the abductors clearly planned a long confinement. Sixty-five hours later, Ezaki managed to loosen his bindings and escape through a small opening, ending the kidnapping but not the intimidation that followed.

Days later, fires were discovered in a company parking area. A plastic container filled with hydrochloric acid and a note warning of further attacks appeared at a Glico factory. What began as a kidnapping now looked like a campaign.

The first letters: taunting police and the press

On May 10, 1984, the first of dozens of letters arrived at Glico and in newsrooms across the Kansai region. Written in casual local phrasing, each ended with the same chilling sign-off — “The Monster With 21 Faces.”

“To the police fools: Are you stupid? You’re working so hard for nothing. Stop us if you can, suckers.”

The messages mocked investigators and threatened to lace Glico candies with cyanide. The tone was confident, familiar, and contemptuous of law enforcement.

Faced with the possibility of poisoned goods, Glico withdrew all products from stores nationwide. The recall crippled sales, cost millions, and forced temporary layoffs of part-time workers.

Retailers cleared their aisles, and families stopped buying sweets. A nation that had built comfort around confectionery suddenly saw danger in the candy aisle.

The man in the baseball cap

Weeks later, security footage captured a man in a Yomiuri Giants baseball cap placing a Glico box on a store shelf. The still image circulated on television and front pages nationwide. The figure’s face was partly obscured, but the frame became iconic — the face of an adversary who could walk calmly into a store while police searched everywhere.

“We forgive Glico”

On June 26, 1984, a new letter arrived.

“We forgive Glico. The president has been returned. We will stop harassing food makers.”

The promise meant nothing. Within days, new letters targeted other companies — Morinaga, Marudai Ham, and House Foods — demanding ransom payments and threatening further poisonings.

The group’s notes were precise. They detailed train lines, car numbers, and specific platforms for money drop-offs. The senders clearly understood commuter schedules and police methods.

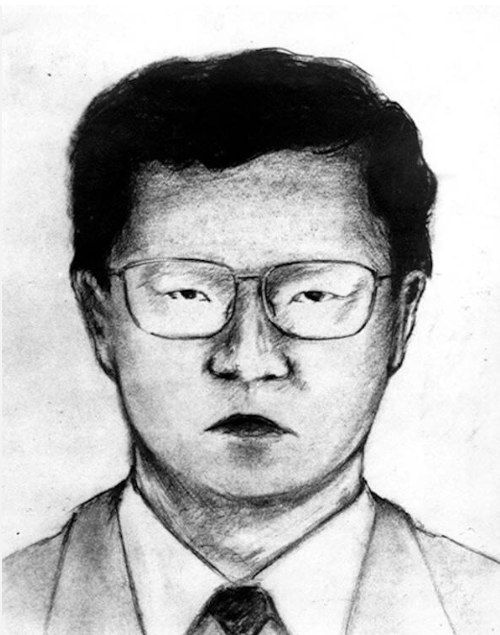

The fox-eyed man

During a ransom handoff attempt for Marudai Ham on June 28, 1984, an undercover officer riding a Kyoto-bound train noticed a short, stocky man with narrow eyes watching him closely. When the planned signal — a white flag — failed to appear, both men left the train separately.

Similar sightings occurred at later handoff points linked to House Foods. In January 1985, police released a composite sketch of the same figure, whose defining feature was his sharp, narrow eyes.

The press named him the fox-eyed man. The image became shorthand for a faceless suspect who had eluded Japan’s largest manhunt.

A scanner, a car, and the realization they were being watched

Not long after, investigators chased a suspicious station wagon near Kusatsu Station. It was found abandoned, engine warm, with a multiband radio scanner inside. The device could monitor police frequencies across several prefectures — proof the group had been listening to tactical chatter and adjusting in real time.

This discovery confirmed what the tone of the letters had already suggested: the criminals were always one step ahead.

“Don’t let bad guys like us get away,” one note taunted. “There’s so much incompetence in your police force. We’ll keep watching you.”

Candy turned to fear

By late 1984, the threats became real. Boxes of Morinaga Choco Balls and Angel Pie appeared on store shelves bearing small white stickers reading “Danger: contains poison.”

Tests confirmed traces of cyanide in several packages. No one died, but the panic was enough to paralyze an entire industry. Candy aisles emptied, and seasonal sales around Valentine’s Day collapsed.

A letter addressed to “Mothers of the Nation” claimed that twenty tainted boxes were in circulation. The phrase was repeated in headlines across Japan, deepening the fear.

A massive manhunt with no clear target

The National Police Agency launched one of its largest inter-prefectural operations, combining resources from Osaka, Shiga, Kyoto, and Hyogo. Stakeouts multiplied. Investigators followed ransom instructions, examined handwriting, and analyzed chemical traces on envelopes.

At one point, writer and activist Manabu Miyazaki was publicly identified and interrogated after his appearance was said to resemble the sketch. He was cleared, and police later apologized. No replacement suspect ever emerged.

The evidence pointed to a small, organized group fluent in urban transport systems, law enforcement radio traffic, and local geography — but there were no fingerprints, no usable DNA, and no eyewitnesses confident enough to name a face.

A tragedy within the investigation

By August 1985, pressure within the police ranks had reached a breaking point. Shiga Prefecture superintendent Shoji Yamamoto, one of the senior investigators, died by self-immolation at his home. His death was covered extensively and marked a dark moment in the case.

Five days later, a final letter arrived.

“We will stop our activities and disappear forever. We are the Monster with 21 Faces.”

After that, nothing more. The letters stopped, and the group vanished.

Rebuilding an industry

When the threats ended, Glico and other confectionery companies faced a long, expensive recovery. They introduced stricter inspection systems, tamper-evident packaging, and improved lot tracking. Retailers added new security cameras at loading docks and storage rooms.

Even small corner stores began logging delivery times and batch numbers. Those changes — born out of panic — helped form the foundation of Japan’s modern product safety standards.

The case also pushed companies and police toward more formal coordination. Large firms began developing internal crisis teams, and law enforcement adopted clearer communication structures for private-sector emergencies.

Legal closure without justice

As years passed, the statute of limitations quietly erased Japan’s chance at prosecution. Kidnapping charges expired during the 1990s. Attempted murder charges related to the cyanide products expired in February 2000.

When that final deadline passed, the National Police Agency issued a rare public statement admitting that, despite one of the largest investigations in Japanese history, no suspect could be charged.

It was a subdued conclusion for a case that had once dominated front pages.

What remains, forty years later

The Monster With 21 Faces case reshaped how Japan thinks about safety, trust, and corporate vulnerability. It remains a benchmark in both criminal and crisis management history — a turning point that forced the food industry to treat contamination threats as a national security concern.

For the public, the image of the man in the Giants cap still defines the mystery. Decades later, he stands frozen in grainy surveillance footage, as anonymous as the letters that mocked the police who could never catch him.

“We’re bad guys,” one of those letters read, “but we have hearts of gold.”

That line, unsettling in its mock sincerity, captured everything about the Monster’s campaign — criminals who seemed to crave spectacle more than money, and a system that could only react, never prevent.

Today, the case is retold in documentaries, police retrospectives, and university courses on crisis communication. No arrests have ever been made, no fingerprints linked, no verified suspects named.

When the Monster declared in its final letter that it would disappear, it kept that promise.