In March 1984, pressure mounted on Japan’s confectionery industry after an audacious abduction in Hyogo Prefecture, and the consequences rippled for sixteen months across factories, rail lines, and newsroom mailrooms.

The case is remembered as the Monster With 21 Faces, an organized extortion and product-tampering campaign that remains unsolved.

On March 18, 1984, two masked men entered the Nishinomiya home of Ezaki Glico president Katsuhisa Ezaki using a key taken from a neighboring residence, then restrained family members and forced Ezaki from the bath.

He was moved to a warehouse in Ibaraki, north of Osaka, where food was left nearby and guards rotated in shifts.

Approximately sixty-five hours after the kidnapping, Ezaki loosened bindings, forced an exit, and reached help, which ended the abduction but not the intimidation.

Fires were then set in a company parking area, and a plastic container filled with hydrochloric acid and a threatening note turned up at a Glico facility, escalating risk calculations inside the company.

Letters began reaching newsrooms and the company on May 10, 1984, each signed by a sender who called itself the Monster With 21 Faces, and written plainly with Kansai phrasing.

The messages taunted police, threatened candy tampering with cyanide, and demanded actions or payments that would be coordinated through precise instructions.

Glico’s first response was nationwide product withdrawal, which carried high costs in recall logistics, disposal, and lost sales, and also forced temporary staffing cuts that affected part-time workers.

Retailers posted notices and cleared shelves, while families avoided sweets entirely, especially where lot tracking seemed confusing. A broader sense of unease set in, extending beyond a single brand.

A security camera later captured a man wearing a Yomiuri Giants cap placing a Glico box on a store shelf, and the still circulated widely without yielding an identification.

The image became one of several fixed reference points for the public, a shorthand that reinforced the idea that the adversary felt comfortable approaching retail displays during active surveillance.

On June 26, 1984, the sender announced that Glico was “forgiven,” which did not return the market to normal rhythm because the letters simply redirected toward other companies.

Morinaga, Marudai Ham, and House Foods received threats, specific ransom instructions, and claims that items on sale had been adulterated.

The sender’s handoff choreography used commuter rail systems, roadside service areas, and timed cues such as white flags or controlled headlight flashes, which exploited schedule predictability and urban density.

Instructions called for specific trains, car numbers, platforms, and signals, and forced company couriers into predictable paths while police tried to track multiple sites without revealing undercover positions.

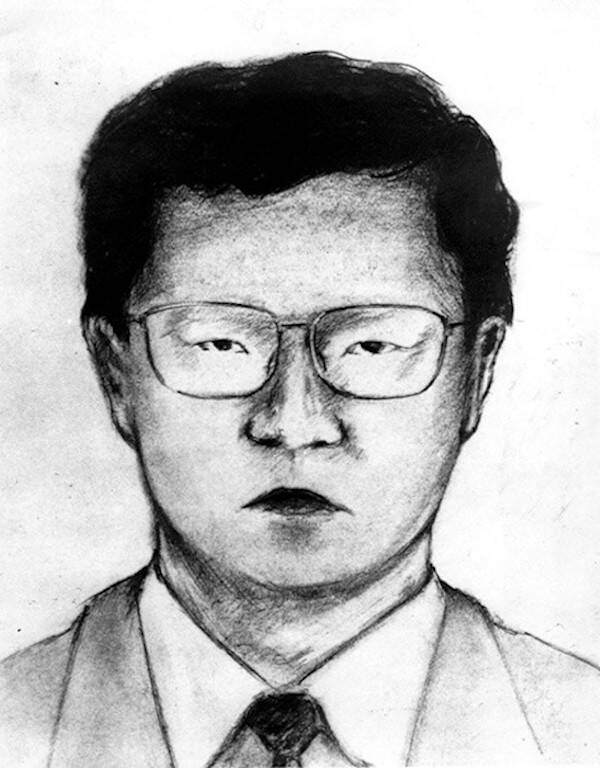

During a Marudai handoff attempt on June 28, 1984, an undercover officer carrying a bag on a Kyoto-bound train noticed a short-haired, stocky observer with narrow eyes who appeared focused on him rather than the crowd.

When the expected flag signal did not appear, the exchange collapsed, and both men left at Kyoto Station without contact.

Investigators would later describe the same man, or a highly similar one, in subsequent sightings linked to House Foods, and the composite released in January 1985 emphasized the distinctive eyes.

The public nickname became the “fox-eyed man,” although the description was a label rather than a confirmed identity, and no arrest followed from the image release.

In another pursuit near a planned money drop, officers chased a suspicious station wagon that was later found abandoned near Kusatsu Station with the engine still warm.

Inside the vehicle, police recovered a multiband radio transceiver capable of monitoring police communications across several prefectures, which confirmed that the adversary listened to tactical chatter and adjusted movements quickly.

The most visible public scare arrived in the autumn of 1984 and early 1985, when packages of Morinaga Choco Balls and Angel Pie appeared on shelves with warning stickers, some actually testing positive for cyanide.

Stores pulled inventory, parents avoided seasonal purchases, and the normal Valentine’s surge in confectionery sales was noticeably dampened as checks continued across multiple cities.

One letter addressed to “Mothers of the Nation” claimed that twenty tainted packages were in circulation, a line reported widely and repeated in later summaries.

Forensic checks confirmed cyanide in a small number of items, but there were no recorded consumer deaths, which kept the legal posture centered on attempted murder and tampering rather than homicide.

As the letters continued, newspapers ran small coded notices under police supervision, which was a familiar tactic in extortion cases that sought to control timing and reduce risk during staged handoffs.

The practice created drop opportunities that often ended with last-second changes or with decoy movements that left officers covering empty platforms or service areas.

The National Police Agency coordinated one of the largest inter-prefectural inquiries of the era, pooling resources from Osaka, Shiga, Kyoto, and Hyogo among others, and publishing periodic updates on leads, stakeouts, and forensic work on the letters.

The scale reflected urgency, although public briefings rarely translated into actionable breakthroughs or even sustained suspect lists with corroborated alibis.

Investigators scrutinized people with past disputes involving the companies, along with individuals whose photographs or public posture resembled the composite image.

Writer and activist Manabu Miyazaki was questioned, his properties were searched, and his alibi checked against key dates, after which police publicly cleared him. No replacement suspect of equal prominence emerged.

Operational details, taken together, suggested a small team that rehearsed timing and understood commuter patterns, highway exits, and law enforcement radio use.

The letters kept a consistent tone, money drops required fine coordination, and the recovered scanner in the Kusatsu vehicle showed an ability to learn in near real time. None of this matured into prosecutable evidence.

Company operations adapted as the months wore on, with security checks at loading docks and packaging lines, revised sign-off procedures, and intensified store-level inspections that required cooperation from retail partners.

Glico worked to restore confidence after the withdrawals, and other brands managed fluctuating production schedules while acknowledging the costs of sweeping checks and the hit to seasonal demand.

The letters, while mocking and plain, showed awareness of police responses and press coverage, and sometimes issued corrections to news accounts or called out investigators directly.

Some notes arrived with instructions that seemed designed to generate public theater without creating redeemable handoffs, which forced police to split resources between the stagecraft and the quiet surveillance work around actual targets.

On August 7, 1985, Shiga Prefecture superintendent Shoji Yamamoto died by self-immolation at his home after intense pressure tied to the ongoing failures to catch the perpetrators, a tragedy reported by domestic papers and international wire services.

Five days later, the Monster sent what is considered the final letter, stating the campaign would end, and no authenticated letters followed.

The immediate corporate aftermath involved rebuilding distribution rhythms, repairing retailer relationships, and restoring consumer trust with visible checks and clearer packaging information.

The longer regulatory and industry response contributed to the spread of tamper-evident features, expanded camera coverage, and refined incident protocols that linked corporate security teams and local police with more structured communication channels.

When the legal clock became decisive, attention turned to limitation periods then present in Japanese criminal procedure, which capped the window for indictment on specific offenses.

Kidnapping counts timed out during the 1990s, while attempted murder tied to cyanide-tainted products expired in February 2000, ending the possibility of prosecution unless new crimes could be charged.

In public statements before that deadline, the National Police Agency conceded that the investigation had not produced suspects who could be charged, a rare admission given the scale of mobilization and the political scrutiny.