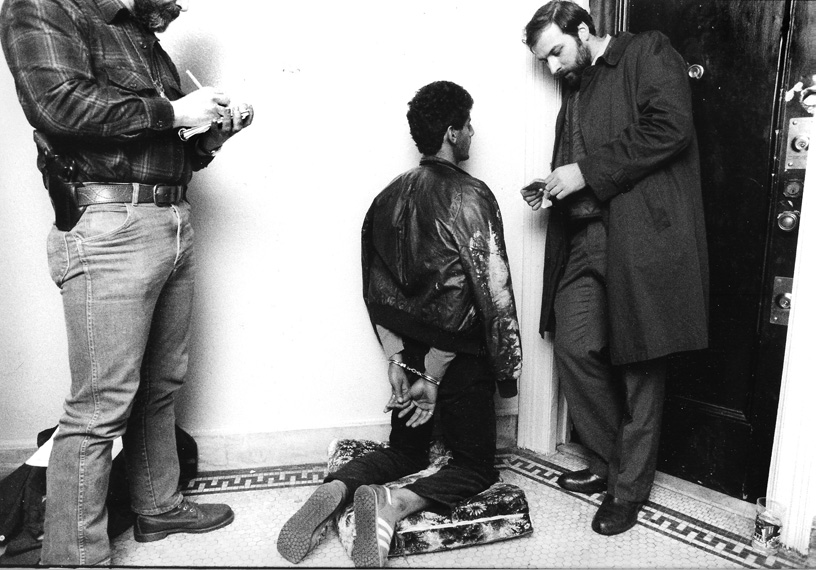

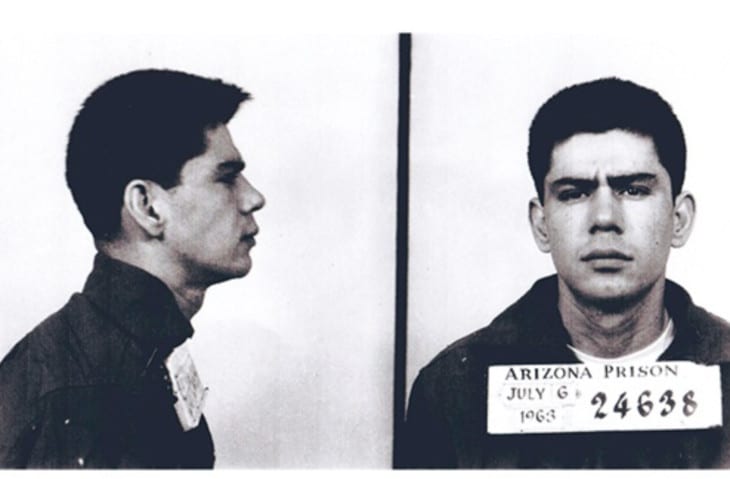

On March 13, 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested in Phoenix, Arizona. Police believed he was connected to the kidnapping and assault of an 18-year-old woman. Officers Carroll Cooley and Wilfred Young picked him up based on circumstantial evidence.

They took him to a small room and questioned him for two hours. Miranda, a 22-year-old high school dropout with a troubled past, eventually confessed. He signed a typed document stating the confession was made voluntarily, without coercion, and with full knowledge of his legal rights.

But here’s the thing. Miranda had not been told he had the right to remain silent. He hadn’t been told he could ask for a lawyer. No one explained that anything he said could be used against him. The “rights” on the confession form were typed, but never spoken. And Miranda, who had a ninth-grade education, didn’t fully understand what he was signing.

In court, his court-appointed lawyer, Alvin Moore, argued the confession should be thrown out. He said it wasn’t voluntary if Miranda didn’t know his rights. The judge disagreed. The confession was admitted, and Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping. He was sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison.

Moore appealed the case to the Arizona Supreme Court. That court upheld the conviction, arguing that Miranda had not asked for a lawyer, so his confession was valid.

Then the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. Representing Miranda was John Paul Frank, a former clerk to Justice Hugo Black. Arizona’s side was argued by Gary K. Nelson.

The Supreme Court heard the case in early 1966. On June 13, 1966, the justices delivered a 5–4 decision that would change American law forever.

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the majority opinion. He said that police interrogations are inherently coercive. If a suspect is in custody, they must be clearly informed of their rights before questioning. If they are not, anything they say cannot be used in court.

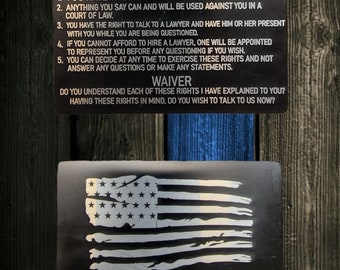

The exact warning spelled out in the ruling went like this: the person in custody must be told they have the right to remain silent, that anything they say can be used against them, that they have the right to a lawyer, and that if they cannot afford one, the state will provide it.

This became known as the Miranda warning. It was added to police procedure nationwide. Officers now carry printed cards to read these rights to every suspect they arrest.

The ruling was controversial. Critics said it would weaken law enforcement and let dangerous criminals go free. Richard Nixon made opposition to Miranda a campaign point. Others praised it as a necessary check on police power and a safeguard for civil liberties.

Miranda was retried in 1967. This time, the state did not use his confession. Instead, a woman named Twila Hoffman, who had been living with Miranda, testified that he had told her about the crime. That was enough to convict him again. He received the same sentence: 20 to 30 years.

Miranda served several more years in prison. In 1972, he was paroled. After that, he returned to Phoenix and lived a quiet, strange life. Ironically, he made money by selling signed Miranda warning cards to police officers. His name had become a legal landmark, and he seemed to embrace the notoriety.

Then, in 1976, Miranda got into a fight in a bar. He was stabbed and killed. The man suspected of the stabbing was arrested, read his rights, and later released due to lack of evidence.

The story didn’t end with Miranda’s death. The decision in Miranda v. Arizona was challenged repeatedly in the years that followed. Some rulings weakened it. Courts allowed spontaneous statements or ruled that some waivers of rights could be implied. Other rulings reaffirmed the original principle.

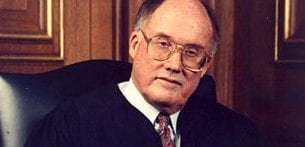

In 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court heard Dickerson v. United States. The federal government had tried to argue that Miranda warnings were not constitutionally required. The Court disagreed. In a 7–2 decision, Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote that Miranda had become part of American culture and could not be undone by Congress.

Later rulings made small adjustments. In Berghuis v. Thompkins (2010), the Court said that suspects had to clearly say they wanted to remain silent. Just staying quiet was not enough. This made it harder to claim your rights without using the exact words.

In 2022, Vega v. Tekoh introduced another twist. The Court ruled that a suspect who had not been given a Miranda warning could not sue the police under civil rights law. This didn’t overturn Miranda, but it removed one way to hold police accountable.

Still, despite all the changes, the core of the decision has survived. Police still start most arrests with the same few lines. Most people know them by heart, even if they don’t always understand them. That’s how deeply Miranda v. Arizona changed American law.

Today, the Miranda warning appears in TV shows, films, and school textbooks. It’s recited in nearly every police drama. It has become one of the most recognizable legal phrases in the world.

Ernesto Miranda, an ordinary man with a long rap sheet and a ninth-grade education, left behind a legacy no one saw coming. His name became a symbol for fairness in the justice system, even as the man himself met a tragic, violent end.