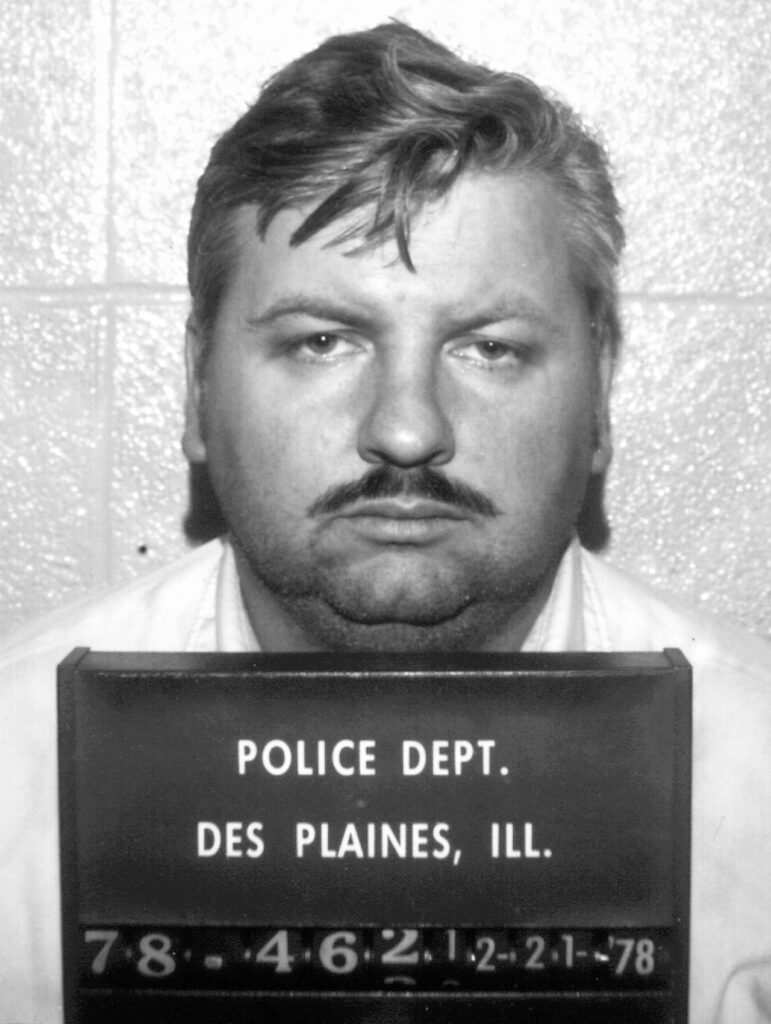

John Wayne Gacy didn’t look like a killer. That’s the problem.

In his world of tidy lawns, handshake deals, and Fourth of July parades, he was the kind of man people trusted. He ran a successful construction company. He threw block parties. He even dressed up as a clown—Pogo the Clown—to entertain sick kids in hospitals. His name was on the local Democratic precinct captain list. His photo was taken with First Lady Rosalynn Carter. He was a “pillar of the community,” whatever that’s worth.

But behind the smile was a man with a second key to your son’s coffin.

What’s terrifying about Gacy isn’t just the body count. It’s how ordinary he seemed. And that ordinariness wasn’t accidental—it was a strategy.

Born in a Basement of Shame

Gacy was born in 1942 in Chicago to a working-class family with rigid, Midwestern values. His father, a machinist and World War I vet, ruled the household with a mix of beer and backhands. Boys didn’t cry. Boys didn’t play with dolls. And boys damn sure didn’t come home with weak hearts or soft gestures, both of which young John was accused of having.

He was overweight. He passed out often due to a congenital heart condition. And he longed for his father’s approval, which never came. His mother tried to defend him, but that only made his father’s scorn more vicious.

“I was never good enough,” Gacy later told investigators. “Even when I did everything right, I was wrong.”

This wasn’t just a sad childhood story. It was the foundation of something darker: a personality shaped by humiliation and desperate performance. Gacy learned early how to wear masks. He became what people needed him to be, especially authority figures. Behind every smile was a transaction—respect in exchange for obedience, approval in exchange for denial.

The Double Life Begins Early

As a teenager, Gacy joined the mortuary sciences program in Las Vegas, where he worked as an attendant at a funeral home. He slept in a cot behind the embalming room. That’s where he says he had his first sexual experience—with a corpse. He fled back to Chicago not long after.

No one in his family knew. They never suspected a thing.

He married Marlynn Myers in 1964, moved to Iowa, and began managing a string of KFCs owned by his father-in-law. He joined the Jaycees, a social and civic club where he quickly climbed the ranks. The man who’d been bullied as a child was now the man with the microphone, the clipboard, the influence.

But Gacy’s craving for control extended far beyond boardrooms and community events. In 1968, he was convicted of sexually assaulting a teenage boy and sentenced to 10 years in prison. The boy had agreed to a ride in Gacy’s car. Gacy drugged him, assaulted him, and threatened him into silence.

The sentence should’ve ended his suburban dreams. It didn’t.

Gacy served just 18 months. His wife filed for divorce. He lost custody of his kids. But when he returned to Chicago in 1970, he repainted himself—new job, new neighborhood, new cover story. He told people the charge was a misunderstanding. He was framed. “It’s in the past,” he said.

And everyone believed him.

Suburbia’s Favorite Son

The Gacy that emerged in Norwood Park wasn’t just reformed—he was magnetic. He opened his own business, PDM Contractors. He hired teenage boys, mostly runaways or kids from troubled homes, and paid them cash. He built up the illusion of success with a manic work ethic and public generosity. He threw parties with open bars and stuffed shrimp trays. He hosted political fundraisers in his backyard. And when the cops knocked, which they occasionally did, he charmed them too.

He was always “helping boys get on their feet.” That’s what he said.

No one thought to ask why so many of those boys disappeared.

Behind the Clown Paint

“Clowns can get away with murder,” Gacy once joked. But the face paint wasn’t a joke. It was armor. When he became Pogo the Clown, he was free to become something grotesque under the guise of joy. The tight makeup, the forced smile, the exaggerated gestures—they weren’t just for kids. They were rehearsals for dominance, rituals of control.

He told psychologists that he was two people: the public Gacy and “Bad Jack.” When Bad Jack came out, he said, he didn’t recognize the man in the mirror. That man liked handcuffs and ropes. That man played a game called “The Rope Trick,” where boys never walked away.

But it wasn’t just a split personality. It was a performance for every audience. And the scariest part? Most of them applauded.

“The System Let Him Go”: Missed Red Flags and Legal Failures

By the time John Wayne Gacy was arrested for the murder of Robert Piest in 1978, there had already been over a dozen moments when he could’ve been stopped. But each time, the system blinked. Or shrugged. Or didn’t even look.

It wasn’t just one mistake. It was a cascade of institutional failures—probation officers who didn’t probe deeper, police who wrote off disappearances, and a society that gave charming men the benefit of the doubt. Gacy didn’t hide in shadows. He hid in plain sight, and no one bothered to pull the mask off.

A Convicted Sex Offender, Rebranded and Untouched

Let’s rewind to 1968. Gacy was convicted of sodomy and sentenced to 10 years in an Iowa prison for luring a 15-year-old boy to his home and sexually assaulting him. The boy had told his parents, reported it to police, and testified in court. Gacy, ever the manipulator, claimed it was consensual and that he was being blackmailed. The jury didn’t buy it.

But here’s where things went sideways.

Despite the seriousness of the offense, Gacy was released in 18 months for “good behavior.” His prison psychiatrist warned that Gacy needed long-term treatment and posed a potential threat. No one followed up. Upon release, he returned to Chicago—and Illinois never required him to register as a sex offender.

This wasn’t a glitch. It was a hole in the system big enough to bury bodies in.

Probation Supervision… in Name Only

After release, Gacy was put on probation. But that turned out to be a rubber stamp. His probation officer met with him a few times, but never investigated his employment or living arrangements. She didn’t know he was hiring teenage boys. Didn’t check in when boys started going missing. Didn’t even follow up after he was questioned in multiple missing persons cases.

He should have still been under scrutiny. But Gacy was polite, punctual, and always knew what to say. “Model probationer,” his file said. Model predator is what it should’ve read.

The Boys Who Disappeared—and the Police Who Didn’t Connect the Dots

Between 1972 and 1976, at least a dozen young men vanished in the area around Gacy’s home. Most were written off as runaways. That’s what the police told the families.

But these “runaways” had patterns. Some were last seen near Gacy’s house. Some had worked for his construction company. A few had even told friends they felt unsafe around him.

But police didn’t investigate further. There was no centralized missing persons database. No follow-up. No real pressure. In one case, a mother tried to tell police her son had mentioned working for a man named “Gacy.” The report was filed—and forgotten.

To many in law enforcement at the time, these weren’t kids who needed to be found. They were kids who didn’t matter.

1975: A Hint of What Was Below

One of Gacy’s employees, 18-year-old John Butkovich, vanished after an argument over unpaid wages. His car was found near his house. His family was frantic. They knew he had gone to confront Gacy.

Police interviewed Gacy. He was calm. Cooperative. He said the boy never showed up. Case closed.

No search warrant. No follow-up.

Later, it was discovered that Butkovich’s body had been buried in Gacy’s crawl space—a place police might have searched, had they taken the complaint seriously.

“It’s Not Illegal to Be Creepy”

Multiple people came forward over the years to say Gacy had propositioned them, grabbed them, even attempted to assault them. He invited young men into his home. Some ran out terrified. Some never came out at all.

But when complaints were filed—if they were filed at all—they were brushed off. “No physical evidence.” “Just a dispute.” “He’s eccentric, not dangerous.”

That mindset—that it’s not illegal to make people uncomfortable—let a serial killer build his graveyard undisturbed.

Robert Piest: The Boy Who Wasn’t Invisible

Everything changed in December 1978. Gacy had approached 15-year-old Robert Piest at a pharmacy where the teen worked. He offered him a job—more money, quick work, just a short meeting. The boy left, telling his mother he’d be right back.

He never came home.

But unlike earlier victims, Robert Piest wasn’t a runaway. His parents were respected. His disappearance got attention. His mother refused to let it go. She told police that Gacy was the last person her son spoke to.

This time, the cops listened. They got a search warrant. They found Gacy’s records. Jewelry that didn’t belong to him. A class ring. And then, finally, the smell that neighbors had mentioned for years—sewage, they said. Dead rats.

No. It was bodies. Dozens of them.

“There Were Always Flies and a Smell”: When the Truth Couldn’t Stay Buried

For years, John Wayne Gacy lived above his own graveyard.

It wasn’t a metaphor. It was literal. Beneath the floorboards of his quiet home at 8213 West Summerdale Avenue in Norwood Park, there was a crawl space just three feet high. Damp. Muddy. Suffocating. And packed with bodies—at least twenty-nine of them, layered on top of each other in a grotesque system Gacy referred to as his “drainage problem.”

Neighbors had complained for years. There was a smell, they said. Sometimes strong. Sometimes faint. Always there.

Gacy explained it away: sewer issues, dead rodents, mildew. Contractors and guests accepted it. No one questioned a respected businessman and party host with a Pogo the Clown costume in the closet. If there’s one thing this story proves, it’s that people will ignore almost anything if it’s wrapped in normalcy.

But when Robert Piest disappeared, the illusion cracked. And when police returned with a second search warrant in December 1978, it shattered.

The Crawl Space Gives Up Its Dead

It began with a single trench. The officers were in Gacy’s house looking for clues—any sign of Piest. One detective noticed a patch of disturbed earth beneath the house, soft and oddly shaped. He reached down and dug a little.

Then came the smell.

Then came a human bone.

Then came the horror.

The scene that unfolded over the next days was unlike anything police had prepared for. Body after body, some skeletonized, others in varying stages of decomposition, pulled from the dirt. Many were bound. Some were still wearing clothing. Most were never officially reported missing.

They were stacked so tightly, investigators had to stop digging at times just to find room for the remains. Gacy had used quicklime to try to mask the smell. It didn’t work.

As the police expanded their search, they realized the crawl space was only part of the story.

Victims in the River

Gacy had run out of room.

When the bodies wouldn’t fit under the house anymore, he started dumping them into the Des Plaines River. That’s where the remains of five additional victims were eventually found. Weighted down, discarded, forgotten—until someone finally started paying attention.

The final victim count would rise to thirty-three. At least. Gacy never kept a list. And many of his victims had no ID, no dental records, no missing persons file. They were drifters, runaways, throwaways in the eyes of the system.

One of the worst details? Some were buried after police had already interviewed Gacy about earlier disappearances. If they’d searched the house just weeks earlier, lives could have been saved.

Who Were the Victims?

Boys. Teenagers. Young men. Most between 14 and 21 years old. Most lured with promises of construction jobs or rides. Some knew Gacy. Some didn’t.

Some were handcuffed. Others were strangled with ligatures. Gacy called it his “rope trick”—a method that allowed him to tighten the noose with a twist of a stick. It wasn’t just about killing. It was about control. Total, irreversible control.

Their names, for years, were less known than Gacy’s. Some still haven’t been identified. They were sons, brothers, students, drifters, kids trying to survive. And Gacy, who played the benevolent employer and father figure, used that desperation against them.

The Last Lie

When he was finally arrested, Gacy was calm. He even confessed—sort of. He claimed he had multiple personalities. That “Bad Jack” did the killing. That some of the victims died accidentally. That others were murdered by accomplices he couldn’t name. He wanted control over the narrative, even as it fell apart.

“I guess I’ve got thirty dead people under my house,” he told officers.

Guess?

It wasn’t a guess. It was a tally.

“Don’t You Write ‘Sick’ on Me”: Gacy in Court and in His Own Words

John Wayne Gacy didn’t walk into his trial hoping for redemption. He walked in thinking he could win.

He’d already confessed to the murders—casually, chillingly, even correcting officers on the details. Yet once the cameras rolled and the courtroom filled, Gacy snapped back into performance mode. He became the contractor again, the businessman, the affable neighbor who had “no idea” how those bodies got there. When that didn’t fly, he pivoted: It wasn’t me. It was Jack. Not a person—an identity. “Bad Jack,” as he called him.

This was Gacy’s final stage, and he was determined to direct the show.

The Trial Begins: A War of Minds

The trial began on February 6, 1980, in Cook County. Gacy faced 33 counts of murder—one of the most staggering charges in U.S. criminal history. His defense? Insanity.

The courtroom became a battleground for psychologists. The defense called expert after expert to argue that Gacy was schizophrenic or suffered from multiple personality disorder. They said he didn’t understand the difference between right and wrong at the time of the killings.

The prosecution said: Bullshit.

Their psychologists diagnosed antisocial personality disorder—meaning Gacy knew exactly what he was doing. He just didn’t care. He manipulated. He lied. He planned. And he enjoyed it.

This wasn’t a man detached from reality. It was a man who dug graves in advance.

Gacy’s Own Words: Contradiction as Defense

Gacy didn’t make things easy for his defense. While they painted him as mentally ill, he kept giving interviews from jail—sharp, coherent, calculated interviews where he denied everything.

“They’re trying to make me look like a sick, twisted individual,” he told the press. “Don’t you write ‘sick’ on me. I’m a businessman.”

To him, the trial wasn’t about guilt. It was about image. Even while facing death, he cared about the perception of strength, masculinity, dominance.

And oddly, part of the public played along. People wrote him fan letters. Women flirted with him. Some journalists—tempted by the theater of the case—gave him airtime to spin his own story.

Gacy didn’t just control his victims. He tried to control his legacy.

The Evidence Was Overwhelming

The prosecution didn’t need to prove motive. They just had to show what Gacy did—and they did. Jewelry belonging to the victims. Employee records. Maps of the burial layout. Even Gacy’s own drawings of the crawl space, labeled with body positions.

It was surgical. Brutal. Deliberate.

They played audio of his confessions, walked the jury through the timeline, and read out the names of boys who vanished into thin air. Some families sat in court, holding old photographs. Others stayed away, unable to face the final truth.

The Verdict: No More Masks

On March 13, 1980, the jury deliberated for just two hours.

Guilty on all counts.

Gacy was sentenced to death—twelve times over.

Even then, he smirked. As if the outcome didn’t faze him. As if, somehow, he still had control.

He wouldn’t be executed until 1994. Fourteen years later. And during that time, Gacy stayed busy. He painted. He sold artwork. He gave more interviews. He called himself the “34th victim,” claiming the state was about to murder him too.

His final words before execution?

“Kiss my ass.”

Not remorse. Not a plea. Just another performance.

The Bodies Talked When the Living Wouldn’t”: Final Reckonings

Even after the last body was pulled from the crawl space, and even after Gacy was sealed into the ground with the same finality he denied his victims, the case wasn’t over. Not for the families. Not for law enforcement. And certainly not for a country forced to reckon with what it let happen.

The Gacy case wasn’t just a turning point in criminal justice. It was a mirror—ugly, unflinching—held up to systems that failed, communities that ignored warning signs, and a culture that mistook being polite for being safe.

The Long Work of Naming the Dead

Of the 33 victims Gacy was convicted of killing, eight remained unidentified for decades. These weren’t just numbers. They were boys whose families never got closure. Bodies buried without names, voices erased by time.

It wasn’t until the 2010s—over 30 years later—that Cook County investigators began re-examining the unidentified remains using modern DNA testing. Families of long-missing boys were contacted. In some cases, cold cases were finally closed. In others, mystery deepened.

One mother submitted her DNA only to learn that her missing son wasn’t among the Gacy victims. But the test matched her to a different long-dead John Doe in another state, reopening a case police had forgotten.

Gacy’s crawl space didn’t just hold the dead. It held answers for families across the country.

Rewriting the Book on How Police Handle Missing Persons

Gacy’s arrest exposed a massive failure in how police tracked missing persons in the 1970s. There was no national database. No cross-jurisdiction communication. No way to flag patterns—like the sudden disappearance of multiple boys working for the same man.

After Gacy, police departments nationwide began developing more systematic ways to connect missing persons cases. The FBI expanded its role. DNA technology would eventually transform identification efforts. And public pressure led to better training on how to handle tips—especially from families of so-called “runaways.”

The system learned—but only after it was too late.

The Serial Killer Next Door

Gacy destroyed the idea that monsters come with warning labels.

He wasn’t a drifter or a social outcast. He didn’t live in isolation or skulk in alleyways. He was a businessman. A taxpayer. A clown at children’s hospitals. The guy who shook your hand at a fundraiser and waved when you mowed your lawn.

He hosted parties while bodies decomposed under his floor.

It changed how America thought about serial killers. The case redefined the “mask of sanity”—the concept that some psychopaths don’t look disturbed. They present as charming, stable, successful. And they rely on that presentation to gain access to victims.

Ted Bundy would follow this script. So would Dennis Rader, the BTK killer. But Gacy showed the country how dangerous normal can be.

What the Gacy Case Still Hides

To this day, some investigators believe Gacy didn’t act entirely alone.

He often claimed others were involved—though this may have been manipulation. Still, he had known connections to Chicago’s underground sex trade and frequently hired drifters and teens who vanished. Could someone have helped dispose of bodies? Could there have been more victims?

One key detail haunts the case: Gacy’s own admission that the number could be higher. “Thirty-three sounds like a nice number,” he once said, smirking. “But who’s counting?”

And then there’s the crawl space map. Some exhumation experts believe there’s evidence of more disturbed earth in the yard and under parts of the garage that were never fully searched. Could more remains lie undiscovered?

We’ll never know. The house was torn down. The crawl space filled in. The land paved over.

Legacy: The Man, the Myth, the Warning

John Wayne Gacy wasn’t the first serial killer America met. But he was the one who changed the way we understood them. He showed us that predators don’t always come in shadows—they come in pressed shirts, with charm and smiles and party invites. They come from the places we’re taught to trust.

The question the Gacy case leaves us with isn’t just “how did he do it?”

It’s: Why didn’t anyone stop him?

And in that silence—across police desks, in courtrooms, in neighborhoods full of willful blindness—we find the real horror.

Not that a monster existed.

But that we let him blend in.