A disease like no other

It began as a whisper, a strange affliction barely noticed amid the chaos of World War I. A handful of cases in Europe, then a few more in the United States.

By 1916, the medical community was beginning to realize something was wrong—people were falling into a bizarre state of near-sleep, unable to wake up fully, unable to move normally.

Some died within weeks. Others recovered, only to be left with permanent neurological damage. And then there were those who neither died nor recovered.

They became statues, trapped in time.

Between 1916 and 1928, a wave of this strange illness swept across the world, infecting an estimated one million people. It was called encephalitis lethargica, or “sleepy sickness,” though the name hardly captured its horror.

The disease didn’t just put people to sleep—it locked them inside their own bodies. Some were frozen in place for decades, their minds still intact but unable to communicate or move. Others developed violent, uncontrollable movements or suffered devastating psychotic episodes.

The epidemic vanished as mysteriously as it arrived, leaving thousands of survivors in asylums, nursing homes, or trapped within their own unresponsive bodies.

Doctors never determined exactly what caused it, and a century later, we still don’t know. The forgotten plague remains one of medicine’s greatest mysteries—a disease without a known origin, a cure, or an explanation.

A Plague of Sleep and Silence

The symptoms of encephalitis lethargica were as bizarre as they were terrifying. It often started with a fever, sore throat, or general fatigue—nothing that seemed particularly alarming at first. But then, something changed.

Patients began to experience uncontrollable drowsiness, slipping in and out of consciousness. Some would fall into a deep, unshakable sleep for days, weeks, even months. Others remained awake but became strangely paralyzed, unable to move normally or respond to stimuli.

For many, it didn’t stop there. Some patients developed Parkinson’s-like tremors, their muscles locking up in rigid, unnatural positions. Others suffered extreme personality changes, growing restless, paranoid, or violent.

Hallucinations were common. So was catatonia—a state where the patient remained frozen, aware of their surroundings but unable to react.

A staggering number of patients—about a third—died in the acute phase of the disease. Others seemed to recover, only to suffer long-term effects that doctors struggled to classify. Some were left with chronic insomnia, unable to sleep at all.

Others became depressed, erratic, or psychotic. And then there were those who developed an almost mechanical stillness—locked in a neurological limbo that medicine could not explain.

For the physicians of the early 20th century, it was a nightmare. Encephalitis lethargica didn’t behave like any other known disease. It wasn’t just an infection, nor was it a typical neurological disorder. It attacked in waves, leaving destruction in its wake, and then—without warning—it was gone.

The Epidemic No One Understood

The first widely recognized outbreak of encephalitis lethargica appeared in 1916 in Vienna, though isolated cases had been noted elsewhere.

From there, it spread like wildfire. By 1917, hospitals across Europe were admitting patients with the same puzzling symptoms—fever, fatigue, and an overwhelming need to sleep. Doctors had no idea what they were dealing with.

Over the next decade, the disease made its way across the world. By 1919, thousands of cases had been reported in North America, South America, and Asia. The worst years were between 1919 and 1924, when the epidemic was at its peak. At least 500,000 cases were recorded, though the actual number was likely much higher.

Some cities were hit particularly hard. In New York, hundreds of patients filled hospital beds, while in London, the epidemic swept through entire neighborhoods.

Medical journals of the time describe patients sitting motionless in hospital wards, their eyes wide open but unseeing. Others were strapped to their beds, thrashing in violent fits of delirium.

One of the most haunting aspects of the disease was its unpredictability. Some patients recovered quickly, never experiencing any long-term effects. Others went into a deep coma and never woke up. And then there were those who seemed fine—until years later, when the illness returned in a different form.

Doctors were at a loss. Was it a virus? A bacterium? A new kind of neurological disorder? Nothing about it made sense.

A Connection to the Spanish Flu?

One of the most controversial theories about encephalitis lethargica is its possible link to the Spanish flu, the devastating pandemic that swept the world between 1918 and 1919.

The timing was suspicious—both diseases emerged around the same time, and many encephalitis lethargica patients reported having flu-like symptoms before developing neurological problems.

But was there a direct connection? Some researchers believe so. They argue that the Spanish flu may have triggered a post-viral autoimmune response, causing the brain to attack itself.

Others suggest that both diseases were caused by the same pathogen, a virus that first manifested as influenza before attacking the nervous system.

The problem? No definitive evidence has ever been found. Despite extensive research, scientists have never identified a specific virus or bacterium responsible for encephalitis lethargica. The flu connection remains an intriguing but unproven theory.

And yet, the similarities are hard to ignore. The Spanish flu left many survivors with long-term neurological issues, including insomnia, depression, and psychosis—symptoms that closely resemble those of encephalitis lethargica. Could they have been two sides of the same coin? Or was the epidemic merely a coincidence, a tragic overlap of two unrelated plagues?

Whatever the answer, the mystery remains unsolved.

The “Awakenings” Patients and the L-DOPA Experiment

For many victims of encephalitis lethargica, the disease wasn’t just an acute illness—it was a life sentence. In the 1920s and 1930s, thousands of survivors were placed in asylums and long-term care facilities, often written off as hopeless cases. Some remained in a near-comatose state for decades, sitting motionless in hospital wards while the world moved on without them.

Then came Dr. Oliver Sacks.

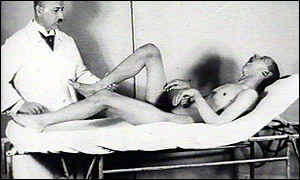

In the late 1960s, Sacks, a young neurologist working at Beth Abraham Hospital in New York, encountered a group of patients who had been institutionalized since the 1920s.

They were victims of the encephalitis lethargica epidemic, frozen in time, seemingly beyond help. But Sacks noticed something strange—many of them had occasional moments of awareness. A flicker of recognition. A sudden movement.

Sacks decided to try an experimental treatment: a drug called L-DOPA, which was being used to treat Parkinson’s disease. The results were astonishing. The patients—some of whom had been catatonic for decades—woke up.

They spoke. They laughed. They moved. Some even danced. It was nothing short of miraculous. For the first time in years, they were alive again.

But the awakening didn’t last. The effects of L-DOPA were temporary, and for many, the side effects were devastating. Some patients experienced uncontrollable movements or wild emotional swings. Others sank back into catatonia, never to wake again.

Sacks later chronicled the experience in his book Awakenings, which inspired the 1990 film of the same name starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro.

The story brought attention to a disease that had been largely forgotten—but it also highlighted the tragic reality of its victims. Even with modern medicine, encephalitis lethargica remained an enigma.

Theories, Speculation, and the Search for Answers

Despite over a century of research, scientists are still debating what caused the encephalitis lethargica epidemic. Several theories have been proposed:

- A viral or bacterial infection – Some researchers believe the disease was caused by a pathogen, possibly a strain of Streptococcus (the bacteria responsible for strep throat and rheumatic fever). Others think a virus, perhaps related to influenza, was to blame.

- An autoimmune reaction – Another theory suggests that encephalitis lethargica was not directly caused by an infection, but by the immune system attacking the brain after a mild illness.

- A neurotoxic reaction – Some speculate that environmental toxins or chemical exposure could have played a role, though no concrete evidence has been found.

The truth is, we still don’t know. No single cause has ever been identified, and modern cases of encephalitis lethargica remain rare and sporadic.

Could It Happen Again?

The thought is chilling: If we don’t know what caused encephalitis lethargica, how can we be sure it won’t return?

Neurologists continue to report occasional cases of patients with eerily similar symptoms. While no epidemic has occurred since the 1920s, isolated clusters have been documented. Could the disease be lying dormant, waiting for the right conditions to strike again?

History has a way of repeating itself. If encephalitis lethargica was caused by a virus, a bacteria, or even a rogue immune response, then it’s not a relic of the past—it’s a potential threat.

A century later, the sleeping sickness lingers as an unsolved medical mystery. It remains a haunting reminder that some of history’s most terrifying diseases don’t just disappear. They wait.