On the morning of March 1, 1954, a small Japanese fishing boat named Daigo Fukuryū Maru or Lucky Dragon No. 5, was drifting through the Pacific near Bikini Atoll. The 23-man crew had already changed course once. They’d lost most of their nets to the sea and were pushing farther south than planned. They were well outside the U.S. military’s posted danger zone. They had no warning nor escort and neither any protection.

At 6:45 a.m., the sky in the west lit up like a second sunrise. A blinding white flash. Then the boom.

They didn’t know it yet, but they’d just witnessed the detonation of Castle Bravo, the largest hydrogen bomb the United States had ever tested. It was catastrophic , far more powerful than American scientists had predicted.

And then came the ash.

Fine white particles began falling from the sky. At first, it looked like snow. Some of the men tasted it. One said it had no flavor. They called it shi no hai or “the ash of death.”

By the time they got back to shore, their skin was blistered. Their eyes red and their hair falling out.

And the tuna they caught? Already on its way to market.

Castle Bravo was a bomb bigger than expected

Castle Bravo was meant to be a test and not a disaster. It was supposed to be a calculated show of strength in the arms race against the Soviet Union. But the calculation was wrong. Badly.

The device used lithium deuteride, a compound American scientists didn’t fully understand. They believed only one isotope would react. They were wrong. All of it reacted. It exploded with more than 15 megatons of force. That’s over 1,000 times the blast at Hiroshima.

The bomb vaporized part of Bikini Atoll. It gouged a crater over a mile wide. And then it sent pulverized coral, dust, and radioactive isotopes into the stratosphere. Winds carried that radioactive plume far beyond the “safe” zone the U.S. Navy had declared.

That danger zone was 57,000 square miles. But fallout eventually covered more than 7,000 square miles of ocean, and much of it landed directly on the Lucky Dragon’s deck.

The U.S. military had no idea the fishermen were there. And even if they had known, the men were technically in international waters.

The Last Voyage of Lucky Dragon No. 5

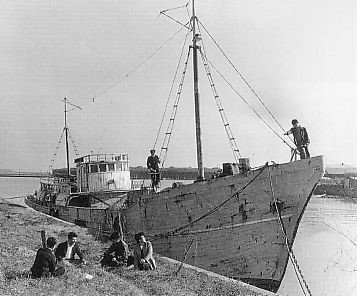

The boat was modest and just under 30 meters long, built in 1947, powered by a 250-horse engine. Originally designed for bonito fishing, it had been refitted for tuna runs. In January 1954, the crew of Lucky Dragon No. 5 left Yaizu Port in Shizuoka for what would be their final expedition.

They were aiming for the Midway Sea near Midway Atoll, but the trip didn’t go as planned. Strong currents and equipment failures cost them most of their nets. With little to show for their efforts, they turned south, closer to the Marshall Islands, unaware that they were nearing a live nuclear test site.

Their last recorded position on March 1 was somewhere around 80 miles east of Bikini Atoll. Some sources say they were 14 miles outside the danger zone. Others dispute whether the crew’s log or navigational records were even consulted later. What’s clear is this: they were not warned. No ship told them to steer away. No aircraft spotted them. No signal alerted them that they were drifting into fallout.

So they kept fishing.

They reeled in shark and tuna that morning. They were still hauling lines when the sky flashed white and the horizon shook. The men had no idea what had just happened, but within hours, they knew something was very wrong.

What Fell from the Sky Wasn’t Snow

First came the flash. Then, several minutes later, the sound—a deep, rolling boom that echoed across the ocean. But it was what followed that truly changed everything.

A fine, white dust began falling from the sky. It coated the boat. It stuck to skin, hair, eyes, and even underwear. It fell into their food, covered their catch, and collected in the corners of their ship. Some men instinctively brushed it away. Others scooped it into bags with their bare hands. One crew member, Oishi Matashichi, even tasted it—just a quick lick. It had no flavor, but a gritty texture. He would later call it “powdered snow.” They didn’t know they were handling radioactive fallout—a deadly mix of uranium, cesium-137, strontium-90, and pulverized coral irradiated by one of the largest bombs ever detonated.

The crew stayed in the area for nearly six hours after the detonation, trying to finish collecting their lines. That delay sealed their fate. The radioactive ash had already penetrated their clothes, entered their lungs, and settled into the pores of their skin.

By nightfall, the symptoms began.

Burning skin. Blinding headaches. Dizziness. Nausea. Diarrhea. Their eyes filled with itchy mucus. Faces darkened. Blisters appeared on arms and legs. Hair began to fall out. One man hung a bag of the fallout near his bunk to have it analyzed—unknowingly keeping a radioactive sample inches from the crew’s heads for the entire journey back.

They started calling the dust shi no hai. “The ash of death.”

And they still had two weeks before they reached home.

The Return Home and Medical Horror

The trip back to Japan took thirteen days. By the third day, the crew’s bodies were breaking down.

Their gums bled. Their skin darkened. Blisters swelled and burst. Noses ran constantly with mucus and blood. Their eyes were bloodshot and raw. Some were too weak to stand. Others began losing hair in clumps. Still, they pressed on. They didn’t fully understand what was happening to them. Radiation was invisible. No one could say for sure what they were suffering from.

They reached Yaizu Port on March 14, 1954, more than a week after Castle Bravo lit the sky.

Their catch—shark and tuna—was still on board. Had they arrived on time, it would’ve been in fish markets across the country by then. But a storm delayed their return. That delay turned out to be a grim stroke of luck. Once signs of radiation were confirmed, most of the contaminated fish was dumped before it ever reached a plate.

The crew reported to the local hospital. The first diagnosis was mild sunburn and exhaustion. They were told to rest.

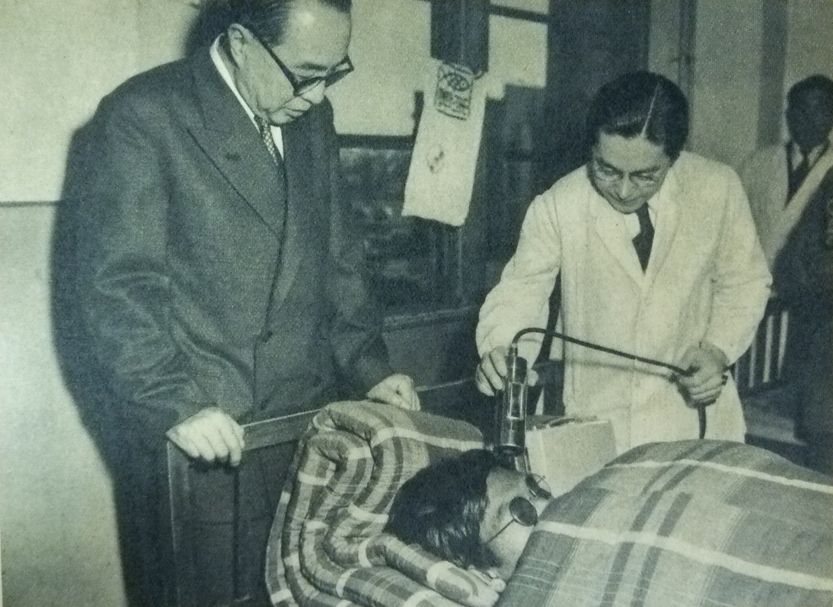

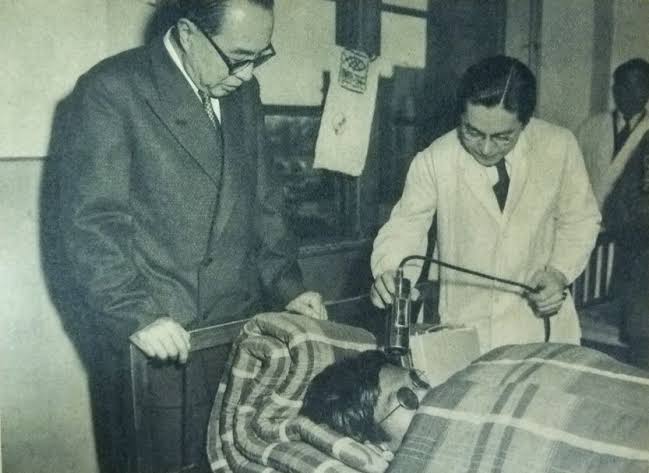

It took another day—and help from Tokyo—for doctors to realize what they were seeing: acute radiation sickness, possibly the first civilian case caused by a hydrogen bomb. One man’s white blood cell count was half of what it should be.

The crew was quarantined. Their clothing was buried in the hospital yard. Their bodies were so contaminated that nurses had to cut their hair off entirely. Geiger counters screamed over their skin and nails.

Their symptoms got worse. Nosebleeds wouldn’t stop. Stools turned bloody. Their fevers spiked. Their immune systems crashed. One man began slipping into delirium. That was Aikichi Kuboyama, the ship’s radio operator. He was 40 years old. And he was dying.

Radiation, Sushi, and Public Panic

It didn’t take long for the news to spread. A fishing boat had come back glowing—and it hadn’t come alone. Its cargo? Hundreds of pounds of radioactive tuna.

At first, authorities tried to stay quiet. But then a reporter saw doctors scanning fish with a Geiger counter. The headline hit: radioactive tuna. That was all it took.

Japan went into panic.

Fish markets emptied. Housewives dumped tuna down drains. Sushi restaurants pulled seafood from menus. Fishermen—many of whom had never sailed near Bikini Atoll—saw their businesses collapse overnight. The fear wasn’t local. It was national. It was existential.

People stopped trusting the sea.

Government officials scrambled. Health inspectors set up emergency testing stations at fishmongers across the country. Tuna was scanned with Geiger counters in full public view. The fallout zone kept growing. By the time things calmed down, more than 400 tons of fish had been recalled or destroyed.

This wasn’t just about food safety. It was about betrayal. Many in Japan still carried deep scars from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Now, less than a decade later, radiation had returned—quietly, invisibly, in the form of sushi.

And worse: it wasn’t war. It was a test.

A U.S. hydrogen bomb had poisoned civilians in peacetime. The Japanese public, already uneasy with its country’s postwar alliance with America, now had a new reason to doubt everything about that partnership.

The Crew’s Long Illness and Government Silence

The 23 crewmen were moved to Tokyo University Hospital, where they would remain for more than a year. Every day brought more tests, more blood samples, more symptoms. They were diagnosed with acute panmyelosis—a condition where the bone marrow stops producing blood. Their red and white blood cells plummeted. Some couldn’t walk. Others bled from the eyes and gums. Sperm counts vanished. Fevers wouldn’t break. Diarrhea became constant.

There was no cure. Doctors prescribed antibiotics, blood transfusions, and bed rest. But the damage was already done.

One by one, the men weakened. The most severe case was Aikichi Kuboyama, the chief radioman. By August, his condition turned critical. He developed meningitis, grew delirious, and had to be tied to his bed. He slipped into a coma, then pneumonia.

On September 23, 1954, he died.

Kuboyama’s final words were, “I pray that I am the last victim of an atomic or hydrogen bomb.”

But even after his death, the U.S. refused to release key medical data. Japanese doctors had written repeatedly to the Atomic Energy Commission asking for help. Their letters were ignored. Eventually, two American scientists were sent—not to offer treatment, but to study the effects of fallout on humans.

Crewman Oishi Matashichi later wrote that Japan’s own Foreign Minister seemed more concerned with appeasing the U.S. than protecting the crew. He said it felt like having an American foreign minister in Tokyo, not a Japanese one.

Even in the hospital, the men were not safe from politics.

Aftermath: Blame, Compensation, and Protest

The United States downplayed everything.

Lewis Strauss, head of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, denied responsibility. He claimed the fishermen had sailed into the danger zone. He even suggested their burns came from burnt coral, not radiation. Privately, he floated a darker theory—that the Lucky Dragon was a Soviet spy ship, deliberately sent to gather fallout for intelligence.

Meanwhile, the fallout map kept expanding. More than 100 fishing vessels had been in the area that day. Many returned with contaminated catch. Public confidence collapsed.

At first, the U.S. offered nothing. Then, after months of outrage and behind-the-scenes negotiation, they paid a one-time lump sum: $2 million for the fisheries, and ¥2 million each to the surviving crew—about $5,500 in 1954 dollars.

Kuboyama’s widow received $2,800.

There were no apologies. No admission of guilt. And no hibakusha status for the crew—which meant no long-term health benefits like the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

But something else happened instead.

Outrage turned into movement. Across Japan, people organized protests, passed resolutions, and founded new anti-nuclear groups. One of the biggest was the Japan Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, which united survivors from Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and now Bikini.

By the end of 1955, nearly 30 million signatures had been collected demanding an end to nuclear testing.

And still, the bombs continued.

Legacy: Godzilla, Memorials, and the Anti-Nuclear Movement

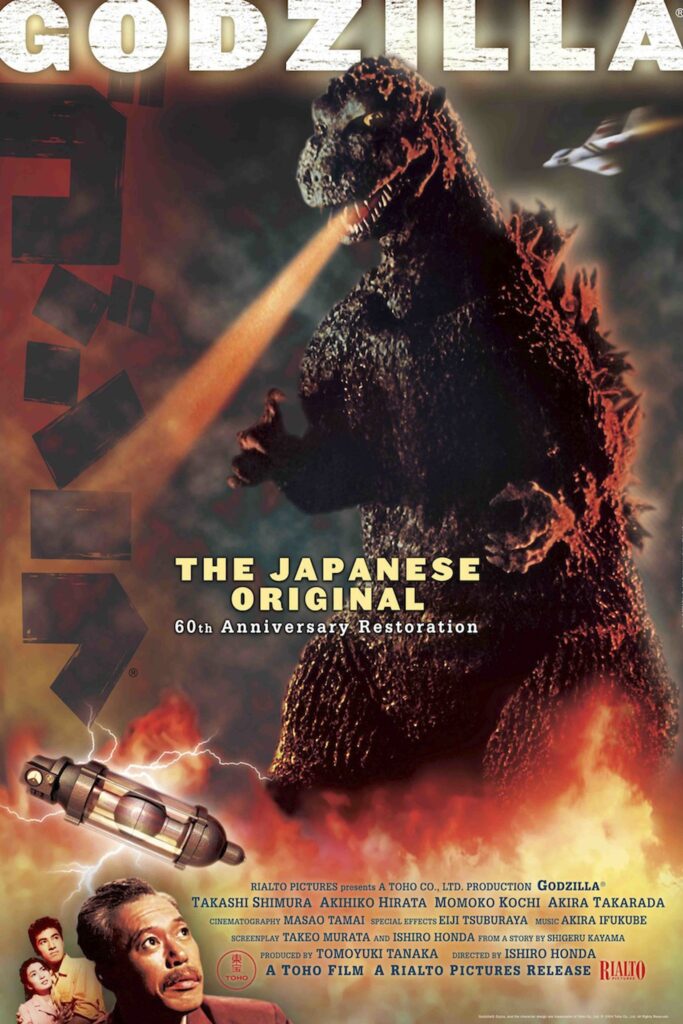

Six months after the Lucky Dragon fallout, Japan met a new kind of monster.

In November 1954, theaters across the country showed Godzilla—a towering, radioactive sea creature born from nuclear testing in the Pacific. It wasn’t just a monster movie. It was a warning. A metaphor. A howl of grief dressed in rubber and smoke.

Godzilla wasn’t science fiction. It was a reaction.

The first scene? A fishing boat destroyed by a mysterious explosion at sea. Audiences didn’t need it explained. They already knew the real name of that boat.

Over time, Daigo Fukuryū Maru became more than a victim. It became a symbol. In 1970, after sitting in disrepair for years, the ship was pulled from a garbage canal and placed in a public museum in Tokyo. A memorial was erected in Tsukiji fish market—a tombstone not for people, but for the tuna that had to be buried.

Survivors like Oishi Matashichi spent the rest of their lives speaking out against nuclear weapons. His child was stillborn. He developed liver disease. He never stopped telling the story.

The U.S. eventually expanded the danger zone. But it was too late. The fallout had already entered water, food, bone, and memory.

Epilogue

The Lucky Dragon wasn’t supposed to be there. The U.S. wasn’t supposed to lose control. The fallout wasn’t supposed to drift that far.

But it did.

And when the ash of death came down like snow, it didn’t just burn skin. It burned trust.

The ocean hadn’t betrayed them. The politics had.

And history never forgets what the sea is made to carry.