Tupac Amaru Shakur was born on June 16, 1971, in East Harlem. He arrived in a courtroom, not a nursery. His mother, Afeni Shakur, was in the final stages of a federal trial, one of the infamous Panther 21 accused of plotting to bomb department stores and police stations across New York. She represented herself. She beat the case. One month after her acquittal, she gave birth.

Tupac’s name carried the weight of revolution. He was named after Túpac Amaru II, the Peruvian revolutionary who was executed by Spanish colonists. His surname came from his mother’s political fire. Afeni was a high-ranking member of the Black Panther Party, part of a generation surveilled, vilified, and fractured by the FBI’s COINTELPRO program.

From birth, Tupac lived inside the tension between surveillance and survival.

A Stage, a Spiral, a Choice

In the early 1980s, the Shakurs relocated to Baltimore. This is where Tupac began to split. On one side, he was a teenager drawn to art, music, and language. He attended the Baltimore School for the Arts, studied ballet and Shakespeare, and performed in The Nutcracker. His best friend was Jada Pinkett. He kept journals filled with introspective poetry.

But the household was unstable. Afeni struggled with addiction. Poverty bit deep. Tupac wrote about food stamps, shame, and hunger. He watched mothers disappear into the criminal system. Every time he walked to school, he passed crack vials on the pavement.

He was learning to perform—but also to protect.

In 1988, the family moved again, this time to California. Tupac, now a teenager, found himself in Marin City, outside San Francisco. His poetry shifted. The armor came on.

Interscope, Shock G, and the First Stage

Tupac joined Digital Underground as a backup dancer and hype man. It was a way in, not a destination. By 1991, he released 2Pacalypse Now. The album was not polished. It was urgent. He rapped about police brutality, single motherhood, and the prison system. Vice President Dan Quayle called it a national threat.

The attention helped Tupac become a star. But it also locked him into a battle between perception and reality. Media saw a menace. He saw himself as a mirror.

Over the next three years, Tupac would make films (Juice, Poetic Justice), drop albums, and get into fights. He once shot at two off-duty police officers in Atlanta. Charges were dropped, but the image stuck.

What few knew was that he was already being watched. The FBI had started tracking him by 1990, linking him to political radicals and gang activity, without clear evidence of either.

The FBI File No One Opened

By the time Tupac was 22, the FBI’s file on him was more than 300 pages. Some of it centered around threats he received. Others documented his affiliations—friends of his mother, cousins, old Black Panthers. The agency tracked his donations, his performances, his lyrics.

But when Tupac was assaulted in 1994, the FBI was silent.

That November, Tupac entered Quad Studios in Manhattan. He believed he was there to record a verse. In the lobby, he was ambushed. Shot five times. Jewelry taken. The shooters walked away.

Tupac survived, but barely. He left the hospital against medical advice, bandages still fresh, and rolled into court in a wheelchair the next day. He had a sexual assault conviction to face.

No federal agency ever investigated the shooting.

Trust Shattered, Thug Life Amplified

The Quad shooting was a turning point. Tupac believed it was more than a robbery. He accused people publicly, including fellow rappers. The East Coast–West Coast feud caught fire. But beneath the headlines was something deeper—he had lost his faith in protection.

Tupac entered prison in early 1995. He was 23. While inside, he read The Prince by Machiavelli. He wrote long letters filled with paranoia and transformation. He studied law and scripture. He also plotted his rebirth.

He signed with Death Row Records while still incarcerated. Suge Knight paid his bail. Tupac left prison and walked into a machine already in motion.

All Eyes on Me and the Deal with Death Row

Tupac released All Eyez on Me in 1996. It was the first double album in hip-hop. It sold five million copies in a year. The persona had hardened—ruthless, theatrical, explosive. But listen closely, and the fear was still there.

The “Thug Life” tattoo was not about crime. It stood for “The Hate U Give Little Infants F***s Everybody.” It was a theory of systemic collapse. Tupac believed that children raised in broken systems became the fury that society feared.

His music was protest disguised as provocation.

Behind the scenes, tensions were tightening. Fights, lawsuits, paranoia. Tupac wanted out. He had recorded enough material to fulfill his contract. He had written a screenplay, Live 2 Tell. He was planning his own label, Makaveli Records.

Las Vegas, September 7, 1996

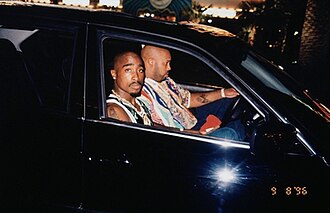

That night, Tupac and Suge Knight were in Las Vegas to watch Mike Tyson fight Bruce Seldon. Tyson won in 109 seconds. Outside the MGM Grand, Tupac got into a fight. Surveillance cameras caught it all. He and his entourage beat a man named Orlando Anderson, allegedly a member of the Southside Crips.

Hours later, Tupac was riding with Suge Knight down Flamingo Road. A white Cadillac pulled up alongside. Thirteen shots were fired. Four hit Tupac.

He died six days later.

No Convictions. No Closure. Only Theories.

Las Vegas police called it gang retaliation. Witnesses vanished. Evidence went uncollected. The case stalled.

Orlando Anderson denied involvement. He was never charged. He died in a gang shootout two years later.

Tupac’s murder remains officially unsolved. But the Las Vegas PD finally arrested Duane “Keefe D” Davis in 2023. He was the uncle of Orlando Anderson and had long hinted at involvement. Davis claimed to be in the car that night. The arrest came nearly thirty years late.

The delay said everything. A Black man murdered in public view. Witnesses, surveillance, motive—and still no justice.

The Makaveli Myth and the Industry’s Resurrection

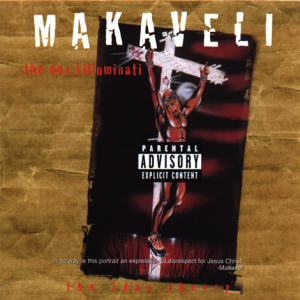

Tupac’s final album, The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, released two months after his death. It was credited to Makaveli. The album cover showed Tupac on a cross. Inside, he rapped like a prophet who had already accepted death.

What followed was a flood. Unreleased songs. Remixes. Posthumous albums. His mother, Afeni Shakur, fought to retain control of his estate. His legacy became a battleground.

Over two dozen albums, documentaries, books, and academic papers have followed. His hologram performed at Coachella in 2012. A Broadway play told his story. A museum exhibit opened in Los Angeles. A 2023 star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was given in his name.

But none of that solved the riddle of who Tupac truly was.

The Ghost in the Machine

To some, Tupac faked his death and escaped to Cuba. To others, he lives on in lyrics that still feel like breaking news. His words are sampled in protest chants and police interrogations. His image appears on murals, T-shirts, and memes.

But beyond myth and merch, Tupac Shakur was a man born into surveillance, forged in poverty, and driven by an intellect the industry rarely understood.

He lived 25 years. He left behind questions that still embarrass systems built to forget.

And the story still refuses to die.