South India is facing a demographic shift that could have far-reaching economic and political consequences.

With fertility rates falling well below the national average, the region is ageing rapidly, leading to concerns over labor shortages, economic stagnation, and a potential loss of political influence at the national level.

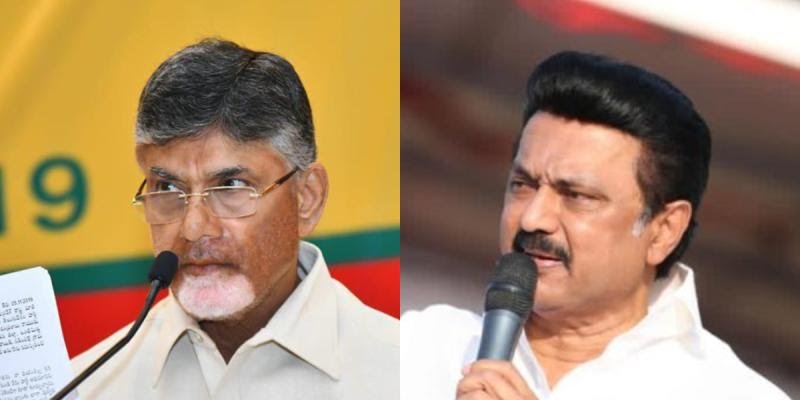

Leaders like Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu and Tamil Nadu’s M.K. Stalin have sounded the alarm, albeit in different ways.

Naidu has gone as far as proposing incentives for larger families, suggesting that only those with more than two children should be allowed to contest local body elections.

Stalin, meanwhile, has highlighted how South India’s slower population growth could cost it parliamentary seats in the upcoming 2026 delimitation, sarcastically quipping, “Why not aim for 16 children?”

The concerns are not unfounded. As northern states continue to grow, the South is at risk of losing its political and economic edge.

An ageing population means fewer working-age individuals contributing to the economy, while a redistribution of parliamentary seats could shift political power toward the North.

If current trends continue, South India may find itself in a weaker position both financially and politically, despite contributing disproportionately to the national economy.

A stark North-South divide in population growth

India may have recently overtaken China as the world’s most populous country, but the growth is not evenly spread.

Northern states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan continue to record higher fertility rates, ensuring a steady supply of young workers and an expanding consumer base.

Southern states, on the other hand, have fertility rates well below the replacement level of 2.1, meaning their populations will soon begin to shrink.

By 2036, states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala are projected to have a median age above 40, while states in the North will still have median ages between 28 and 32.

This ageing crisis is likely to create a host of economic challenges. A declining workforce could lead to labor shortages, reduced productivity, and a shrinking tax base.

With fewer young people supporting a growing elderly population, healthcare and pension costs will rise, placing a heavy burden on state finances.

The contrast is clear. While the North faces the challenge of creating enough jobs for its young and expanding workforce, the South is struggling with the opposite problem—too few young people to sustain economic growth.

What this means for the economy

One of the most immediate effects of a declining birth rate is a shrinking labor force. With fewer young workers entering the job market, industries dependent on a steady supply of labor—such as manufacturing, services, and agriculture—could struggle to find employees.

Lower birth rates also translate into lower consumer demand. Fewer young families mean slower growth in sectors like housing, retail, and education, leading to a potential economic slowdown in the South.

Public finances will also take a hit. With a higher proportion of elderly citizens, state governments will need to allocate more resources to healthcare and social services, while collecting less in taxes. This could strain state budgets, forcing difficult decisions on spending priorities.

Northern states, by contrast, are experiencing the opposite trend. A younger workforce provides the potential for higher economic growth, but only if jobs can be created at the same pace. Failure to do so could lead to rising unemployment and social unrest.

The political fallout of South India’s population decline

Perhaps the most significant consequence of this demographic shift will be felt in India’s political landscape. Since parliamentary representation is based on population, the upcoming 2026 delimitation exercise could result in South India losing several seats, while North Indian states gain more.

For decades, the number of parliamentary seats allocated to each state was frozen at 1971 levels to prevent states that controlled their population growth from being penalized.

This freeze is set to be lifted in 2026, meaning states with larger populations—primarily in the North—will gain seats, while those with slower growth—mainly in the South—will lose them.

Estimates suggest that South Indian states could collectively lose around 26 seats, while Uttar Pradesh and Bihar alone could gain about 21. Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan are also expected to see an increase in their representation.

This shift could have profound political consequences. Currently, the five South Indian states hold about 24 percent of the total 543 Lok Sabha seats, giving them significant influence in national policymaking.

After 2026, that number is expected to drop to around 20 percent. This means that even if all South Indian MPs were to vote together on an issue, they would no longer have the numbers to block a constitutional amendment requiring a two-thirds majority.

Stalin has warned that this could lead to a political marginalization of the South, reducing its ability to shape national policies in its favor. With more seats concentrated in the North, decision-making power would increasingly shift away from South Indian states, despite their larger contributions to the national economy.

A growing financial imbalance

South India’s economic strength has long been a point of pride, but it also presents a financial challenge. While the region contributes significantly more to the central tax pool, it receives far less in return.

For every rupee contributed in taxes, states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Maharashtra receive far less than they give. Maharashtra, for example, gets back only 8 paise for every rupee it contributes. Tamil Nadu gets 58 paise, and Karnataka receives 50 paise.

In contrast, northern states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh receive far more than they contribute. Bihar, for instance, receives Rs 7.26 for every rupee it pays into the central pool, while Uttar Pradesh receives Rs 2.49.

This imbalance is largely due to the way central funds are allocated. Since population size is a key criterion, states with larger populations receive a bigger share of tax revenues.

With northern states continuing to grow, they stand to receive an even larger share in the future, further widening the financial gap.

Southern leaders have long argued that this system is unfair, particularly given that their states have been more successful in economic development, healthcare, and education. The growing disparity in financial allocations could lead to increasing resentment and demands for a fairer distribution of resources.

How South India is responding

In response to these challenges, Chandrababu Naidu has taken a controversial step—actively encouraging families to have more children.

Andhra Pradesh MP Kalisetti Appala Naidu has announced that he will personally offer Rs 50,000 to women who give birth to a third child, with an additional incentive for families that have a boy.

The state government has also expanded maternity leave policies, allowing women to take paid leave regardless of how many children they have.

But while such incentives may slow the decline in birth rates, they are unlikely to reverse the trend entirely. Cultural and economic factors mean that most urban families are choosing to have fewer children, prioritizing education and career stability over larger families.

Instead of focusing solely on boosting birth rates, experts suggest that South India should invest in alternative solutions.

Encouraging higher labor force participation among women and senior citizens, improving automation in industries facing labor shortages, and pushing for a fairer distribution of central tax revenues could all help mitigate the economic and political risks of a declining population.

For now, the divide between North and South India is growing—not just in population numbers, but in economic power and political influence. If these trends continue, they could fundamentally reshape India’s federal structure, with consequences that will be felt for decades to come.