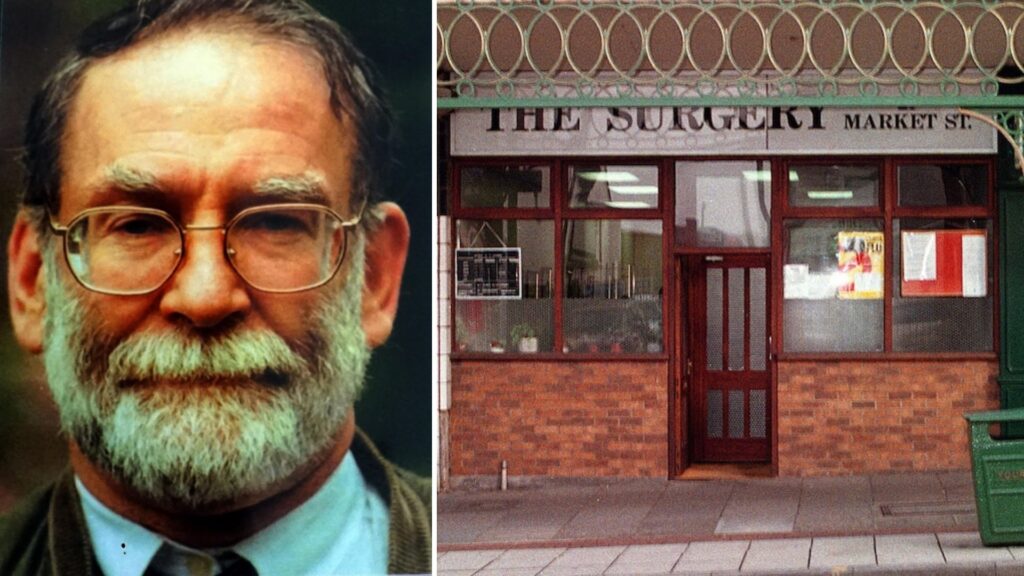

Harold Frederick Shipman was an English general practitioner who worked mainly in and around Hyde, Greater Manchester. He was arrested on September 7, 1998, and on January 31, 2000, he was convicted of murdering 15 patients and forging a will.

Shipman was born on January 14, 1946, on the Bestwood Estate in Nottingham. His father, also Harold Frederick Shipman, worked as a lorry driver. His mother, Vera Brittan, died of lung cancer on June 21, 1963.

Shipman was 17 when his mother died. In the later stages of her illness, she received morphine at home from a doctor. Shipman later described watching how her pain eased after injections, before she died.

He began medical studies at Leeds University Medical School in 1965. On November 5, 1966, he married Primrose May Oxtoby. They later had four children. He graduated from Leeds in 1970 and entered hospital posts.

In 1970, Shipman received provisional registration with the General Medical Council and worked as a pre registration house officer in surgery at Pontefract General Infirmary. In 1971, he moved into a pre registration post in medicine at the same hospital.

In 1974, Shipman moved into general practice. He became an assistant general practitioner and then a GP principal at the Todmorden Group Practice, based at the Abraham Ormerod Medical Centre in Todmorden, on the Lancashire and West Yorkshire border.

In 1975, concerns surfaced about Shipman’s controlled drug prescribing. Large quantities of controlled drugs were being prescribed, and it became clear he had been forging prescriptions to obtain pethidine for his own use.

Shipman underwent treatment at The Retreat, a psychiatric centre in York, from early October to late December 1975. The matter still proceeded through the criminal justice system, focused on dishonest obtaining of drugs and forged NHS prescriptions.

In 1976, Shipman was convicted at Halifax Magistrates Court of dishonestly obtaining drugs, forgery of National Health Service prescriptions, and unlawful possession of pethidine. He was fined on each charge and ordered to pay compensation.

During 1976, Shipman worked as a clinical medical officer in South West Durham. He was not removed permanently from medicine at that stage. He later returned to general practice, which became a major focus of criticism after his later crimes.

In 1977, he joined the Donneybrook House Group Practice in Hyde, then part of Cheshire, as a general practitioner. Over the next years he built a stable professional life in Hyde and continued working there through the 1980s.

In 1983, Shipman appeared in a Granada Television World in Action episode about how mentally ill people should be treated in the community. The appearance later became notable because it showed him operating publicly as a credible local doctor.

By the early 1990s, Shipman moved to operate from The Surgery at 21 Market Street, Hyde. He was working as a single handed GP, meaning he ran the practice himself without partners, which reduced day to day internal oversight.

The killings for which Shipman was convicted involved lethal injections of diamorphine. The prosecution case was that he administered diamorphine during visits, usually in patients’ homes, then documented the deaths as natural, often using expected sounding causes.

Diamorphine is a controlled opioid used medically for severe pain, including in end of life care. In Shipman’s case, it became central evidence because toxicology and clinical context indicated administration that did not match legitimate treatment in the situations examined.

A recurring feature across the investigated deaths was timing and setting. Many of the deaths occurred at home rather than in hospital. Many occurred when Shipman was present, often during his afternoon visiting rounds, and were then certified by him.

Another recurring feature was record keeping after death. Police and inquiry reviews later identified instances where entries were made into computerised medical records after the patient died, describing symptoms or history in a way that supported a natural death narrative.

Cremation paperwork also mattered. Shipman regularly completed cremation forms and asked other local doctors to countersign. The volume and pattern of these forms, particularly involving elderly women, became one of the earliest concrete warning signals in Hyde.

On March 24, 1998, Dr Linda Reynolds, a GP principal at the Brooke Practice on Market Street, reported concerns to John Pollard, HM Coroner for the Greater Manchester South District. The concerns centred on the number of Shipman’s patient deaths and circumstances.

At the coroner’s request, Greater Manchester Police carried out a confidential investigation. Detective Inspector David Smith led it under Chief Superintendent David Sykes. The investigation concluded there was no substance to the concerns and ended on April 17, 1998.

Later inquiry work found major problems with that first police response, including how evidence was gathered and evaluated. The absence of a detailed contemporaneous written report also became an issue once the later homicide investigation began.

After the first police inquiry closed, Shipman continued killing. Inquiry summaries state that three patients were killed before his arrest later that year, including Winifred Mellor, Joan Melia, and Kathleen Grundy, whose death triggered the second investigation.

Separate concerns also reached police from outside the medical community. In August 1998, taxi driver John Shaw told police he suspected Shipman of killing patients, describing repeated situations where elderly passengers appeared stable but later died under Shipman’s care.

Shipman’s last confirmed victim in the criminal case was Kathleen Grundy, a former mayoress of Hyde. She was found dead at her home on June 24, 1998. Shipman was the last person known to have seen her alive.

After her death, Shipman signed the death certificate and recorded the cause of death as old age. That explanation drew attention because Grundy had been described as functioning independently, and the death appeared sudden to people who knew her.

The case escalated because of what happened with Grundy’s will. Grundy’s daughter, Angela Woodruff, a solicitor, was informed by fellow solicitor Brian Burgess that a new will existed and that there were doubts about its authenticity.

The will excluded Woodruff and her children and left the bulk of Grundy’s estate to Shipman. The amount was reported as £386,000. The structure and quality of the document raised immediate suspicion within the legal handling of the estate.

Woodruff went to police in July 1998, reporting her belief that the will was forged. The investigation began as a forgery case, but quickly shifted toward homicide once investigators considered how Grundy had died and who benefited from her death.

Grundy’s body was exhumed. Toxicology testing found morphine in her tissues, consistent with diamorphine administration because diamorphine breaks down into morphine in the body. That finding conflicted with a death attributed simply to old age.

Shipman tried to explain the drug finding by claiming Grundy had been an addict. He pointed investigators to comments in her computerised medical record. Police examination of his computer showed those entries had been written after her death.

When police searched Shipman’s possessions and premises, they found a Brother typewriter consistent with the type used to produce the forged will. The will evidence and the toxicology evidence reinforced each other and supported an arrest decision.

Shipman was arrested on September 7, 1998. He was initially suspected in relation to Grundy’s death and the will. From there, the police inquiry widened to examine other deaths he had certified, focusing on sudden, unexpected home deaths.

Investigators built a set of “specimen” cases that were strong enough for prosecution, based on timing, clinical notes, certification patterns, and forensic findings from exhumations. The aim was to present a coherent, provable pattern to a jury.

The charging decision ultimately focused on 15 deaths between 1995 and 1998, all involving female patients. The prosecution position was that Shipman administered lethal injections of diamorphine, then recorded causes of death that masked homicide.

Shipman’s trial began on October 5, 1999, at Preston Crown Court. He faced 15 counts of murder and one count of forgery related to Kathleen Grundy’s will. His legal team tried to have the Grundy case tried separately.

The court rejected the attempt to split the trials. Prosecutors argued the will provided motive evidence for at least one murder and showed a willingness to fabricate documents. The combined trial allowed jurors to see the will and the medical evidence together.

The 15 victims named in the indictment were Marie West, 81; Irene Turner, 67; Lizzie Adams, 77; Jean Lilley, 59; Ivy Lomas, 63; Muriel Grimshaw, 76; Marie Quinn, 67; Kathleen Wagstaff, 81; Bianka Pomfret, 49.

The indictment also included Norah Nuttall, 65; Pamela Hillier, 68; Maureen Ward, 57; Winifred Mellor, 73; Joan Melia, 73; and Kathleen Grundy, 81. These cases were presented as representative of the wider suspected pattern.

Medical experts gave evidence about the expected clinical course of the patients and the implications of morphine levels in postmortem testing. The prosecution case was that the drug findings and circumstances were incompatible with normal GP care.

The jury retired and deliberated for six days. On January 31, 2000, Shipman was found guilty of 15 counts of murder and one count of forgery. The verdict established him as a serial killer operating inside routine primary care.

Mr Justice Forbes sentenced Shipman to life imprisonment on all 15 murder counts, with a recommendation for a whole life tariff. He also received four years for forging Grundy’s will, to run concurrently with the life sentences.

On February 11, 2000, Shipman was struck off the medical register by the General Medical Council. The conviction and professional removal did not end the public process, because questions remained about how many people had died and how oversight failed.

On February 1, 2000, the Secretary of State for Health, Alan Milburn, announced an inquiry into the case. An initial plan for a private inquiry under Lord Laming was later abandoned after judicial review challenges succeeded.

In September 2000, the government announced a public inquiry under the Tribunals of Inquiry framework. Dame Janet Smith, a High Court judge, was appointed chair. Public hearings began in June 2001 and were structured in phases and stages.

The inquiry examined individual deaths, death certification, cremation safeguards, controlled drug handling, and the performance of institutions responsible for monitoring primary care. It also reviewed the 1998 police response and the coroner’s involvement.

In its work, the inquiry concluded Shipman had killed at least 215 patients over a period of 24 years. That conclusion went far beyond the criminal convictions and was based on detailed review of cases where unlawful killing was supported on the evidence.

The inquiry also mapped how Shipman avoided scrutiny. It documented repeated deaths that should have been reported to a coroner because they were sudden or unexpected, yet were not referred, in part because Shipman asserted he could certify a cause.

The inquiry found that the system in place did not deter Shipman and did not detect his killings while they were occurring. It recommended changes to death registration, cremation certification, coronial processes, and monitoring of controlled drugs.

While imprisoned, Shipman maintained his innocence and did not provide a confession. Additional prosecutions were not pursued after conviction, with authorities citing the level of publicity and the reality that 15 life sentences already ensured he would not be released.

Shipman remained in custody and was held at HM Prison Wakefield. On January 13, 2004, he died by suicide in his cell, hanging himself the day before his 58th birthday. A postmortem and inquest process followed.

The Shipman Inquiry continued after his death, issuing further reports through 2004 and a final report in January 2005. Its published material included detailed timelines, institutional findings, and recommended reforms designed to prevent repetition.

The main factual record that remains is a progression from early controlled drug misconduct in the mid 1970s, to long term GP practice in Hyde, to abnormal death patterns flagged in March 1998, then a failed early police inquiry.

It then moves to the Kathleen Grundy death on June 24, 1998, the forged will report in July 1998, exhumation findings of morphine, Shipman’s arrest on September 7, 1998, and a widened homicide investigation using exhumations and records.

The criminal case ended with convictions on January 31, 2000, based on 15 sample murders and one will forgery, and the public inquiry later concluded he killed at least 215 people over 24 years, with multiple systemic failures identified.