What Happened in The Dalles, Oregon, in 1984?

In 1984, 751 residents of The Dalles, a small city in Oregon, fell seriously ill from food poisoning. It wasn’t accidental. Salad bars at ten local restaurants had been deliberately contaminated with Salmonella bacteria.

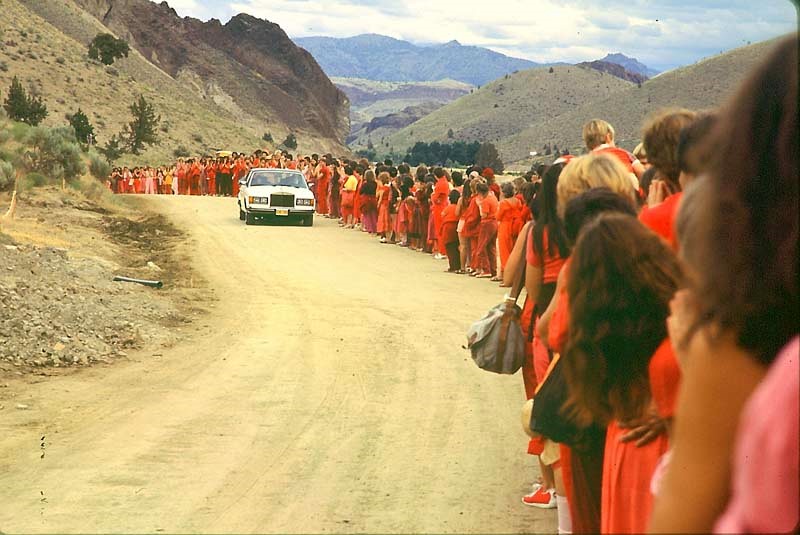

The culprits were followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, also known as Osho, a controversial spiritual leader who ran a nearby commune called Rajneeshpuram.

Led by Ma Anand Sheela, the group intended to incapacitate voters in The Dalles to win the 1984 Wasco County elections. This event would become known as the largest bioterrorist attack in U.S. history.

Rajneesh’s followers had previously gained political control of Antelope, a tiny nearby town, renaming it “Rajneesh.” Their ambition grew: they wanted seats on the Wasco County Circuit Court and the sheriff’s office.

Concerned they wouldn’t get enough votes legally, some commune officials planned to incapacitate voters in The Dalles, the largest city in Wasco County. They selected Salmonella enterica Typhimurium, initially testing it on two county commissioners through contaminated glasses of water, before escalating the contamination to salad bars and salad dressings across the city.

As a result, 751 people contracted salmonellosis. Forty-five of them were hospitalized, though fortunately, none died. Initially, Oregon health officials and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) couldn’t confirm deliberate contamination.

However, on February 28, 1985—nearly a year later—U.S. Congressman James H. Weaver publicly accused the Rajneeshees of deliberately infecting salad bars.

At a press conference in September 1985, Rajneesh himself accused several followers of crimes including this poisoning and an aborted assassination attempt of a U.S. Attorney, urging authorities to investigate further.

This triggered a multi-agency investigation led by Oregon Attorney General David Frohnmayer, involving the Oregon State Police, FBI, and other federal officials. When investigators searched Rajneeshpuram, they found a medical lab containing samples of Salmonella matching the strain used in the attacks.

Eventually, two Rajneeshee leaders were convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 20 years, though they served only 29 months in federal prison.

The Planning Behind the Attack

The story began in 1981, when thousands of Rajneesh followers settled onto the “Big Muddy Ranch” in rural Oregon, creating the commune of Rajneeshpuram. Initially welcomed by some locals, relations quickly soured due to disputes over land use and rapid expansion.

After seizing political control of Antelope, the commune attempted to extend their influence across Wasco County. In preparation for the November 1984 election, they sought control over two county commissioner seats and the sheriff’s office.

To influence election outcomes, the commune introduced the “Share-a-Home” program, importing thousands of homeless individuals into Rajneeshpuram to register them as voters.

However, the Wasco County clerk thwarted this effort by imposing strict requirements on voter registration. Frustrated, Rajneeshpuram’s leadership turned to darker tactics: intentionally sickening voters in The Dalles to reduce voter turnout.

About a dozen people were involved in the bioterror plot, with key figures including Ma Anand Sheela, Rajneesh’s chief lieutenant, and Diane Yvonne Onang (Ma Anand Puja), a nurse practitioner overseeing medical operations. They purchased Salmonella bacteria from a medical supplier in Seattle, cultivating it in commune laboratories.

The group first considered this contamination a “trial run,” with intentions of expanding the operation closer to election day, though the second phase never materialized because the commune later boycotted the election when their imported voters were prevented from voting.

Initially, two visiting Wasco County commissioners became the test subjects, unknowingly drinking Salmonella-tainted water at Rajneeshpuram on August 29, 1984. Both men fell seriously ill; one required hospitalization.

Afterward, the perpetrators attempted contaminations in grocery stores, the county courthouse (including doorknobs and urinal handles), and multiple restaurant salad bars. Their courthouse and grocery store efforts failed, but the contamination of salad bars proved devastatingly effective.

How the Attack Was Carried Out

In September and October of 1984, Rajneeshee agents covertly contaminated salad bars at ten restaurants around The Dalles. Perpetrators carried small plastic bags filled with a Salmonella solution—referred to by the attackers as “salsa”—which was either secretly spread onto salad ingredients or mixed into dressings.

By late September, more than 150 people became violently sick. Symptoms ranged from severe diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and chills to abdominal pain and bloody stools.

Victims spanned all ages, from an infant born shortly after his mother was infected, to an elderly resident aged 87. Local health systems were overwhelmed, businesses suffered financially, and frightened residents avoided dining out or even leaving home.

One resident recalled the atmosphere as “horrified and scared,” adding, “people wouldn’t go out alone; people became prisoners in their own homes.”

Local suspicion quickly fell upon the Rajneeshees. Despite their illness and fear, local residents turned out in unprecedented numbers to vote, determined to prevent Rajneeshee political victories.

The commune’s political ambitions were thwarted—of their nearly 7,000 residents, only 239 voted, as most weren’t U.S. citizens. Shortly thereafter, authorities would confirm local fears: this was no ordinary outbreak—it was deliberate biological terrorism.

Investigating the Attack

After hundreds fell violently ill, authorities from multiple agencies quickly mobilized. Officials from the Oregon Health Authority, Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and local public health departments initially conducted investigations into the outbreak, identifying Salmonella enterica Typhimurium as the culprit.

At first, they attributed the widespread contamination to poor hygiene among restaurant workers, who themselves had become sick.

Yet, this explanation didn’t satisfy everyone. Oregon Congressman James H. Weaver felt there was more to the story, and he pushed investigators to look harder at Rajneeshpuram.

Weaver publicly voiced suspicion on February 28, 1985, claiming Rajneeshees deliberately contaminated the salad bars. His accusations were initially viewed as alarmist or politically motivated by some observers. Nonetheless, Weaver’s persistence helped keep the case open.

The turning point came months later, in September 1985. Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh himself, after years of public silence, suddenly called a press conference.

Rajneesh accused his trusted lieutenant Ma Anand Sheela and 19 others of committing serious crimes, including poisoning local residents and plotting to assassinate public officials. He dramatically urged law enforcement to investigate his own commune.

Though Rajneesh’s claims initially prompted skepticism, authorities acted swiftly. Oregon Attorney General David Frohnmayer formed a special task force composed of Oregon State Police, the FBI, Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), and the National Guard.

On October 2, 1985, fifty investigators descended on Rajneeshpuram, executing extensive search warrants.

The results of this raid were alarming. Investigators discovered laboratory equipment and Salmonella bacteria matching the exact strain used in the attack on The Dalles. They uncovered experiments involving poisons, chemicals, and biological agents conducted throughout 1984 and 1985.

Officials also found explosive-making literature, military bio-warfare guides, and an invoice for Salmonella typhi, which causes deadly typhoid fever.

Court testimony revealed that Rajneeshee operatives also boasted privately of other unproven attacks, including alleged poisonings at a nursing home and the Mid-Columbia Medical Center.

Further revelations shocked investigators: the commune had plotted but ultimately aborted an assassination attempt on Charles Turner, the former U.S. Attorney for Oregon.

Who Knew About the Plan?

As evidence mounted, Rajneeshpuram’s leaders quickly turned against each other. The mayor of Rajneeshpuram, David Berry Knapp (Swami Krishna Deva, also called “KD”), became an informant for the FBI, offering chilling testimony.

KD stated Ma Anand Sheela claimed she had discussed the plot directly with Rajneesh himself. According to KD, Sheela told followers not to worry if their actions resulted in deaths, citing supposed approval from Rajneesh through vaguely recorded conversations.

These allegations, however, remained contested. Followers described Sheela’s habit of editing Rajneesh’s recorded speeches to manipulate their meaning, thus clouding whether Rajneesh genuinely approved the attack.

John Jay Shelfer, Sheela’s husband, recalled years later that Sheela skillfully manipulated vague statements from Rajneesh to justify her own agenda.

Many Rajneeshees believed Rajneesh knew about Sheela’s illegal activities, though concrete proof never emerged. Scholars continue debating whether Rajneesh was an active participant or an isolated figure whose silence inadvertently empowered Sheela.

Rajneesh later claimed Sheela exploited his self-imposed isolation to establish a “fascist state” within the commune, yet he acknowledged that his withdrawal enabled her power.

The Aftermath and Arrests

On October 27, 1985, Rajneesh attempted to leave the U.S. by plane but was arrested upon landing in Charlotte, North Carolina, facing multiple immigration violations.

In a plea deal, he admitted guilt on two counts of immigration fraud, received a suspended sentence, a $400,000 fine, and deportation. However, he never faced charges directly related to the bioterror attack.

Ma Anand Sheela and Ma Anand Puja fled the country but were arrested in West Germany on October 28, 1985. Following lengthy extradition negotiations, both women returned to the United States in February 1986.

Charged with attempted murder, assault, poisoning, product tampering, wiretapping, and immigration fraud, they entered Alford pleas—maintaining innocence while recognizing the overwhelming evidence against them.

Sheela received multiple concurrent sentences totaling up to 20 years, primarily for attempted murder and assault, while Puja received sentences of up to 15 years. Yet both women served only 29 months before early parole due to good behavior.

Sheela’s U.S. residency was revoked, and she later moved to Switzerland, remarried, and began managing nursing homes.

In the end, what began as a desperate plot for political power unraveled dramatically, exposing the dark underbelly of a commune that once promoted peace and enlightenment.

Long-Term Impact and Public Reaction

The Rajneeshee bioterror attack left deep scars on The Dalles and reshaped America’s understanding of domestic terrorism. Restaurants in The Dalles suffered significant financial damage; nearly all affected businesses eventually closed permanently.

Residents remained frightened long after the immediate threat subsided, haunted by the realization that trusted neighbors had secretly carried out such violence.

In the aftermath, Oregon Attorney General David Frohnmayer publicly described the Rajneeshees’ crimes as unprecedented in their severity. He called the event “the largest mass poisoning” in U.S. history and emphasized how dramatically it exposed public vulnerabilities.

Local investigative journalism played a crucial role in bringing details to light. Starting in June 1985, The Oregonian newspaper ran a landmark twenty-part investigative series detailing the Rajneeshpuram commune’s hidden operations.

Journalist Leslie L. Zaitz, a central figure in exposing Rajneeshpuram’s criminal activities, was later discovered to have been placed third on a hit list compiled by Sheela’s group—a chilling reminder of the lengths the cult was willing to go.

The incident triggered broader concerns about the potential of bioterrorism attacks in the United States.

Milton Leitenberg, a leading researcher in bioweapons, later noted that no other terrorist group had managed to culture pathogens so effectively, underscoring how unique and dangerous the Rajneeshee attack was.

Public Health Lessons and Media Silence

Health officials grappled with difficult lessons from the outbreak. Michael Skeels, former director of Oregon’s Public Health Laboratory, reflected that the incident permanently altered their sense of safety. He bluntly stated, “We lost our innocence over this.”

Health authorities requested that detailed accounts of the attack remain unpublished for twelve years, fearing copycat attacks. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) complied, finally publishing an extensive analysis of the attack in 1997.

Despite initial secrecy, no repeat attacks followed. The CDC later identified factors motivating bioterrorism through this incident, including charismatic leadership, paranoia, and defensive aggression.

The Rajneeshee attack checked nearly all of these boxes, except an apocalyptic ideology. Researchers and public health officials now use the event as a critical case study in identifying bioterror risks.

Cultural and Historical Legacy

The story resurfaced in public consciousness following the 2001 anthrax attacks, with renewed media interest in how bioterror could emerge domestically.

Judith Miller’s influential 2001 book, Germs: Biological Weapons and America’s Secret War, prominently featured the Rajneeshee attack, prompting widespread reflection on the potential for bioweapons use.

The Dalles’ residents, long overshadowed by the trauma of the attack, found themselves thrust into the national spotlight again. They understood perhaps better than anyone how easily bioterrorism could infiltrate everyday life, permanently changing their view of public safety and trust.

In 2005, Rajneeshpuram’s land was sold to Young Life, a youth ministry group, symbolically ending a chapter in Oregon’s troubled history. Yet, reminders lingered: the tiny town of Antelope commemorated resistance to the “Rajneesh invasion” with a plaque at their post office, marking the community’s resolve.

Experts cite this incident, alongside Japan’s Aum Shinrikyo cult, as rare examples of successful biological terrorism by non-state actors. It remains America’s single largest bioterror attack—fortunately, one without fatalities.

Historian Joseph T. McCann noted in 2006 that, while the Rajneeshee plot failed politically, its scale and impact remain unparalleled.

Ultimately, the Rajneeshee attack serves as a chilling reminder of how charismatic leadership, unchecked power, and deep-seated paranoia can combine catastrophically.

Though Rajneesh himself avoided prosecution for the attack, his legacy was forever marred. Ma Anand Sheela, though serving minimal prison time, never returned to public influence in America.

Today, the Rajneeshee bioterror attack is more than just historical trivia. It stands as a stark warning about the hidden dangers within communities, highlighting how fragile trust can be—and how quickly peaceful ideologies can spiral into violence.

Not sure when this article appeared – someone forwarded me an old article, but thought I would comment anyway!

As a resident of “Rajneeshpuram” and a sanyassin (disciple/ follower) of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh… only the crazy (seriously crazy) Sheela and a few of her “gang” had anything to do with or knew anything about this crazy, horrible and STUPID plan.

She basically put an end to a great experience / experiment in living in peace and harmony/love.

So sad for all of us.

(Of course being from the south [Georgia] I [a privileged white man] found it interesting to be discriminated against!)

Peace and Love to all.

That’s fascinating John! How accurate did you find this article? I would love to live on a comune but they always seem to end badly

fascinating, especially since the USA is now run by an actual cult.