On Aug. 29, 2002, Audrey May Herron finished her shift and left Catskill, New York, at about 11 p.m. She got into her black 1994 Jeep Grand Cherokee and headed for home, but she never arrived.

Herron, born Oct. 4, 1970, was 31 years old at the time. She was a mother of three, and her family has said she was dedicated to her children and her work as a nurse.

The New York State Police describe her as 5 feet tall and about 105 pounds, with hazel eyes. In official listings, the case is labeled “under suspicious circumstances,” and investigators have continued to ask the public for tips.

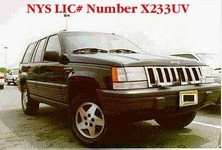

Herron was last seen driving westbound on State Route 23 in the town of Catskill. Police have said her black Jeep, with New York license plate X233UV, disappeared with her and has never been found.

She was wearing dark green medical scrubs and a blue turtleneck when she left work. A case summary also notes a yellow-gold “#1 Mom” pendant necklace and a watch with a white leather band.

The last known drive

Herron worked part time as a nurse at the Columbia-Greene long-term care facility in the Jefferson Heights area of Catskill. She had made the commute for years, according to The Vanished podcast’s case write-up.

Her home was in Freehold, New York, about 12 to 15 miles from the facility. The distance matters because it narrows the window in which something happened, and because searchers have focused on the same stretch for years.

Multiple sources describe bad weather that night. Case summaries and later reporting say there was rain, and some accounts also mention fog in the area as she left work.

In one reconstruction, Herron walked out with coworkers, reached her Jeep, and said goodnight. Investigators later focused on those final minutes because they are among the last points where her movements were confirmed by others.

A Crime Watch Daily report, later published by True Crime News, describes what police were told about the parking lot. A lieutenant said the coworkers walked out together, said goodbye, and drove out, placing Herron at her Jeep moments before the disappearance.

The same report says one coworker told investigators that Herron was behind her for about five minutes after leaving. After that, the coworker said they took different paths, leaving roughly ten minutes before Herron should have been home.

That short window is why the case draws attention decades later. In many missing-person cases, a vehicle turns up quickly, even if the person does not, but investigators in Herron’s case have said they did not find the Jeep.

The hours before

Reporting and case summaries describe a normal day leading up to her shift. In one account, Herron spoke with family that evening and shared news about a pay raise, sounding upbeat.

The Charley Project notes that Herron had a doctor’s appointment scheduled for the next day, which she never attended. That detail is often used by family and supporters to argue she was not making plans to disappear.

The same summary says her phone and credit cards have shown no activity since she vanished. Investigators have not publicly explained what they learned from phone records, but her lack of traceable activity remains part of the documented timeline.

Herron was expected home around 11:30 p.m., according to the Charley Project’s compilation. When she did not arrive, the absence was noticed quickly, and the following morning turned into calls to relatives and her workplace.

The search begins

Case accounts differ slightly on the first hours, but the core sequence is consistent. In one telling, her husband reported her missing around 6 a.m., after realizing she had not come home from the overnight shift.

The True Crime News version adds that her stepmother had ties to state police headquarters and helped route the information to investigators. A state police sergeant said he received a call around 10 a.m., and troopers moved quickly.

Investigators initially treated the disappearance like a potential crash because of the weather and the rural roads. The same sergeant said a helicopter was deployed that afternoon to check the route for signs of a vehicle leaving the roadway.

Searchers looked for skid marks, broken guardrails, and damaged brush, but the early sweeps did not produce physical evidence. The True Crime News report describes an “exhaustive search” of the roughly 12 miles between work and home that turned up nothing obvious.

That absence of evidence shaped the investigation. The sergeant in the Crime Watch Daily report said the case started to feel unusual a few days in, when the Jeep still had not been found, because many cases end with a recovered vehicle.

Over time, police and volunteers expanded the search methods. In the same reporting, investigators described using ATVs, dog teams, and repeated checks of bodies of water along the direct route and possible detours.

They also went door to door, according to the state police sergeant quoted in the report. He said investigators spoke with residents and property owners within an eight-mile radius of her home, trying to capture sightings and unusual activity.

Years later, the case was still active. In a 2017 CBS6 report, police said they had followed hundreds of leads and still had not located Herron or her Jeep, and they urged anyone with information to come forward.

The Jeep that never surfaced

The missing vehicle remains central because it limits what investigators can prove. Without a car, it becomes harder to test a crash theory, harder to locate a crime scene, and harder to confirm whether she ever left the route she was believed to take.

The New York State Police description is specific: a 1994 black Jeep Grand Cherokee with New York plate X233UV. The Charley Project adds that the Jeep lacked fog lamps and had minor damage to the front passenger-side bumper.

Police have not said publicly whether the Jeep’s condition suggested recent repairs or whether the bumper damage was old. Still, supporters return to the same point: a large SUV disappeared without being recovered from a roadside, lot, or waterway.

The route itself has been scrutinized repeatedly. Friends and family have described the drive as short, and one of Herron’s friends told CBS6 that people have “scoured” it, focusing on the idea that locating the Jeep could break the case open.

Leads and theories

Investigators have discussed two broad possibilities: an accident that left no visible trace, or foul play. In Crime Watch Daily’s reporting, a lieutenant said the lack of a vehicle pushed them toward the idea that “something horrible” happened.

Some accounts suggest she might have changed routes because of weather. The Charley Project notes fog and rain and says she “may have taken a shortcut,” which would widen the search area beyond the direct path.

Friends have also repeated crash scenarios, including the idea of a wooded drop-off or waterway swallowing a vehicle. Those ideas persist because of the road conditions described that night, but police have said repeated searches of waterways have not produced the Jeep.

Another line of discussion involves an encounter that ended with Herron and her Jeep being taken together. Investigators have not publicly described evidence of carjacking, but the combination of a missing driver and a missing vehicle keeps abduction theories alive.

There has also been rumor-based talk about whether Herron’s family connections made her a target. Crime Watch Daily’s report recounts a “Russian mob” rumor tied to a golf course her husband’s family owned, and says police looked into it, but no ransom call came.

The Times Union described other worries that circulated inside the family. Herron’s mother suggested possibilities like an intruder surprising her as she got into the Jeep, or anger linked to an eviction dispute tied to a golf course property where the family lived.

Investigators also questioned people closest to her, as is standard in missing-person cases. In the Crime Watch Daily reporting, police described her husband as cooperative at times and less so at others, while stressing that suspicion alone was not evidence.

A widely cited case summary says police described her husband as uncooperative, and that he disputed that characterization by pointing to a polygraph and multiple searches of his property. Police have not publicly named him as a suspect, according to that summary.

The Times Union reported that, by 2016, Herron’s mother said she had heard state police were scouring a property with a pond after receiving information and that a possible suspect had come up. A state police spokesperson declined to comment at the time.

In 2022, WNYT reported that the State Police Underwater Recovery Team searched Maurer’s Lake, the Potuck Reservoir, and part of Catskill Creek after receiving new reports. The station said the search turned up nothing and the Jeep remained missing.

Family pressure, public memory

Even as leads stalled, Herron’s family and friends kept the case visible. In 2017, CBS6 quoted her mother and her oldest daughter reflecting on the strain of not knowing what happened, and asking anyone with information to contact police.

WNYT reported that Herron’s oldest daughter, Sonsia Court, was 10 when her mother vanished. The station said she remembered their last conversation on the day she returned from a trip with her grandmother, and that she had held onto that moment.

In the same 2017 CBS6 report, a friend, Marie Parker, said she maintained a memorial site near where Herron was last seen and did not want people to forget. Police said then that the investigation remained active and that leads were still being followed.

CBS6 revisited the case again in 2025 and included Parker’s frustration about the missing Jeep. She said finding the vehicle would provide a first “piece of the puzzle,” and she described years of repeated searching along the same short route.

Fundraisers became another way to keep attention on the case. WNYT reported that Court hosted “Riding for Audrey,” a motorcycle event held in remembrance of her mother, and linked the effort to broader support networks for families searching for missing relatives.

That 2022 WNYT fundraiser story also referenced Mary Lyall’s Center for Hope, founded after the disappearance of Suzanne Lyall, as a local resource for families facing long-term uncertainty. The station emphasized that missing-person cases rarely end without public help.

Where the case stands

Officially, Herron remains listed as missing under suspicious circumstances. The New York State Police entry still places her last known location on Route 23 in Catskill at 11 p.m., with the black Jeep Grand Cherokee and plate X233UV.

Police have not announced an arrest, identified a suspect publicly, or reported the discovery of the Jeep. In public statements carried in news reports, investigators have continued to say they need a break, even a small detail, to move the case forward.

Tips can go directly to investigators. The New York State Police Troop F Bureau of Criminal Investigation in Catskill lists a contact number of (518) 622-8600, and multiple news reports have repeated that request.

If disappearances that begin as an ordinary errand interest you, you may also want to read our deep dive on the disappearance of Dorothy Jane Scott, a California mother who vanished after a quick trip to the hospital and was later linked to years of anonymous phone calls.

Sources and Reporting Notes

This article is based on official missing-person case summaries, contemporaneous and archival local reporting, and later follow-up coverage documenting renewed searches and public appeals.

Primary details regarding Audrey May Herron’s last confirmed sighting, clothing description, vehicle make and plate number, and the case’s classification as “under suspicious circumstances” were drawn from the New York State Police missing-person entry.

Core biographical details, the consolidated disappearance timeline, and vehicle identifiers were cross-referenced with the Charley Project case file, which compiles publicly available law-enforcement information and widely cited case notes.

Official federal database identifiers and baseline case fields were verified against the NamUs entry for Herron (MP668), which is maintained through the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.

Reporting on later investigative activity, including State Police underwater searches at Maurer’s Lake, the Potuck Reservoir, and portions of Catskill Creek, was drawn from regional news coverage by the Times Union (May 9, 2022) and WNYT (May 9, 2022).

Family and community statements, including references to a memorial site and continued public appeals, were drawn from local reporting by CBS6 Albany (WRGB), including its 2017 update and a later Evidence Room feature (2025).

Additional context about long-running community attention and earlier retrospective reporting was supported by archived Times Union coverage, including a 2016 report.

Fundraising and remembrance efforts were also referenced via archival Times Union coverage of a motorcycle ride held in her honor, Riding for Audrey (2011).

A broader popular-audience recap that draws from the Crime Watch Daily segment was reviewed via True Crime News (2017).