On the morning of 20 September 1988, nineteen year old Tara Calico left her house in Rio Communities, New Mexico, for a bike ride and never came back.

Thirty seven years later, investigators say they know what happened and who did it, but no one has been charged yet.

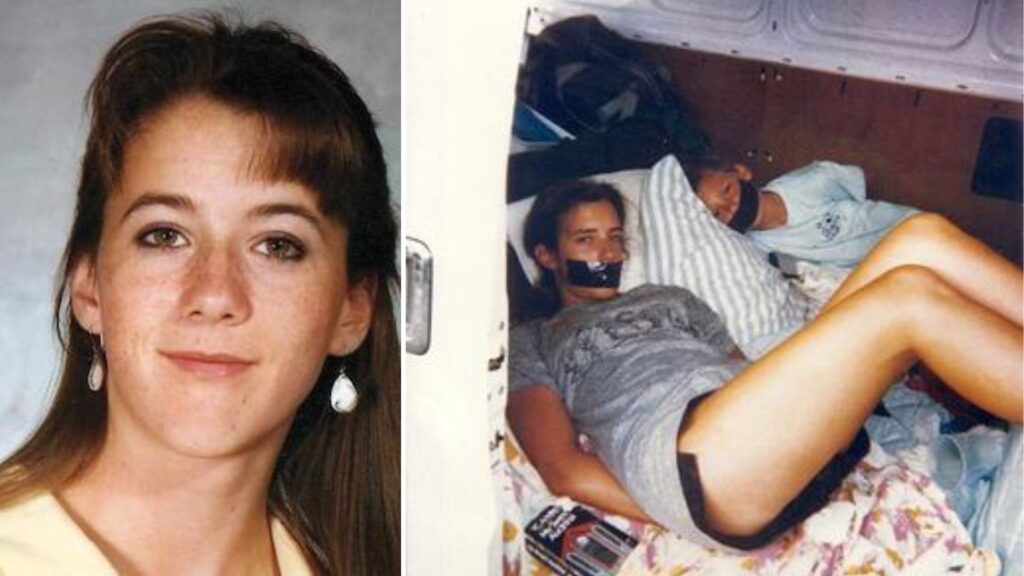

Her disappearance became famous because of a single Polaroid photograph found the next year in a parking lot in Florida. The picture showed a young woman and a boy, gagged and apparently bound in the back of a van, with a paperback novel lying beside them.

For Tara’s family, that image felt like a message. For investigators today, it looks more like a long running distraction from what probably happened much closer to home.

Tara before the case

Tara Leigh Calico was born in 1969 and grew up in Belen, a small city in Valencia County, New Mexico. Her parents, David Calico and Patty Doel, separated when she was young, and Tara lived with her mother, who later married John Doel.

Friends remember Tara as energetic, organised and social. She played sports, did well at school and seemed to collect people wherever she went. According to local reporting, she could be stubborn when she set her mind on something, including her daily routines.

She graduated from Belen High School in 1987 and enrolled at the University of New Mexico’s Valencia campus, where she studied psychology. At the same time, she worked part time at the First National Bank of Belen and kept a busy schedule that left little empty space in her day.

Tara also had a boyfriend, former classmate Jack Cole. Articles that interviewed him describe a straightforward relationship built around shared activities, road trips and an active lifestyle, with no sign that she planned to leave home or change her life suddenly.

The road she rode every morning

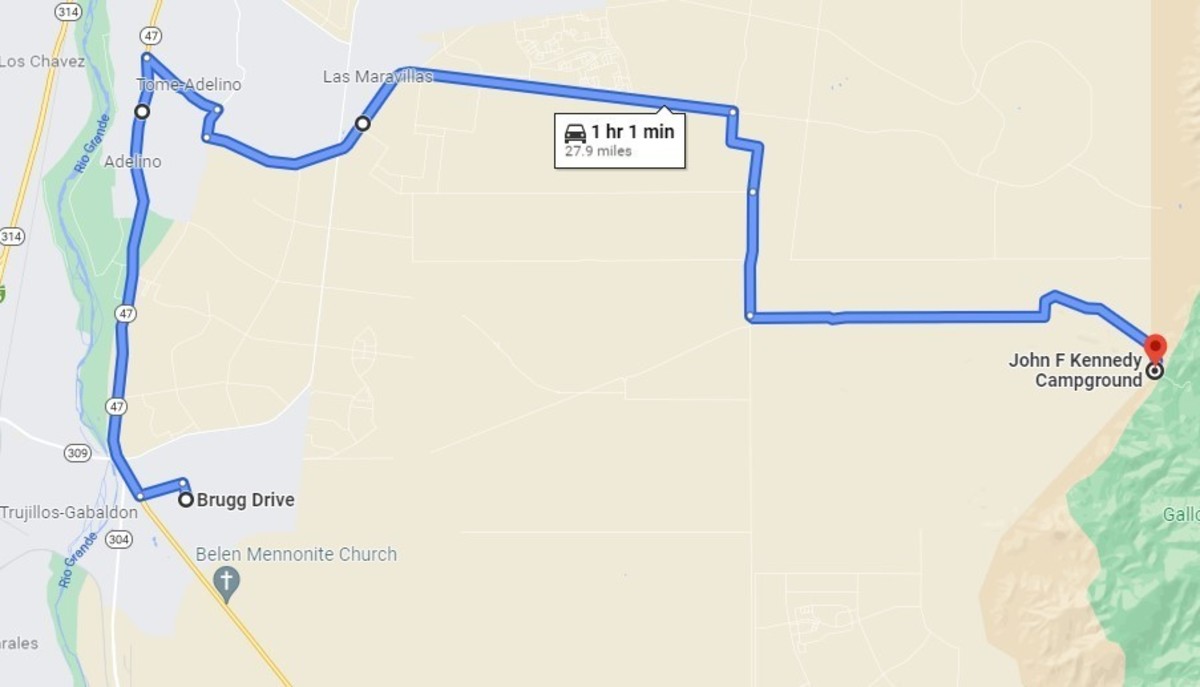

By 1988, Tara had built a strict routine around a 36 mile bike ride along New Mexico State Road 47. She usually left around 9.30 in the morning, rode north toward the town of Los Lunas, then came back in time for classes, work or social plans later in the day.

She normally used her mother’s neon pink Huffy mountain bike because her own was damaged. On the day she vanished, witnesses later told police she wore a white T shirt with the First National Bank of Belen logo, white shorts with green stripes and white and turquoise athletic shoes.

At first, Patty joined her daughter on those rides. That changed after she felt a driver was stalking them on the highway. She told police that a motorist had made her so uneasy that she stopped riding with Tara and began warning her to carry mace. Tara refused and kept going out alone.

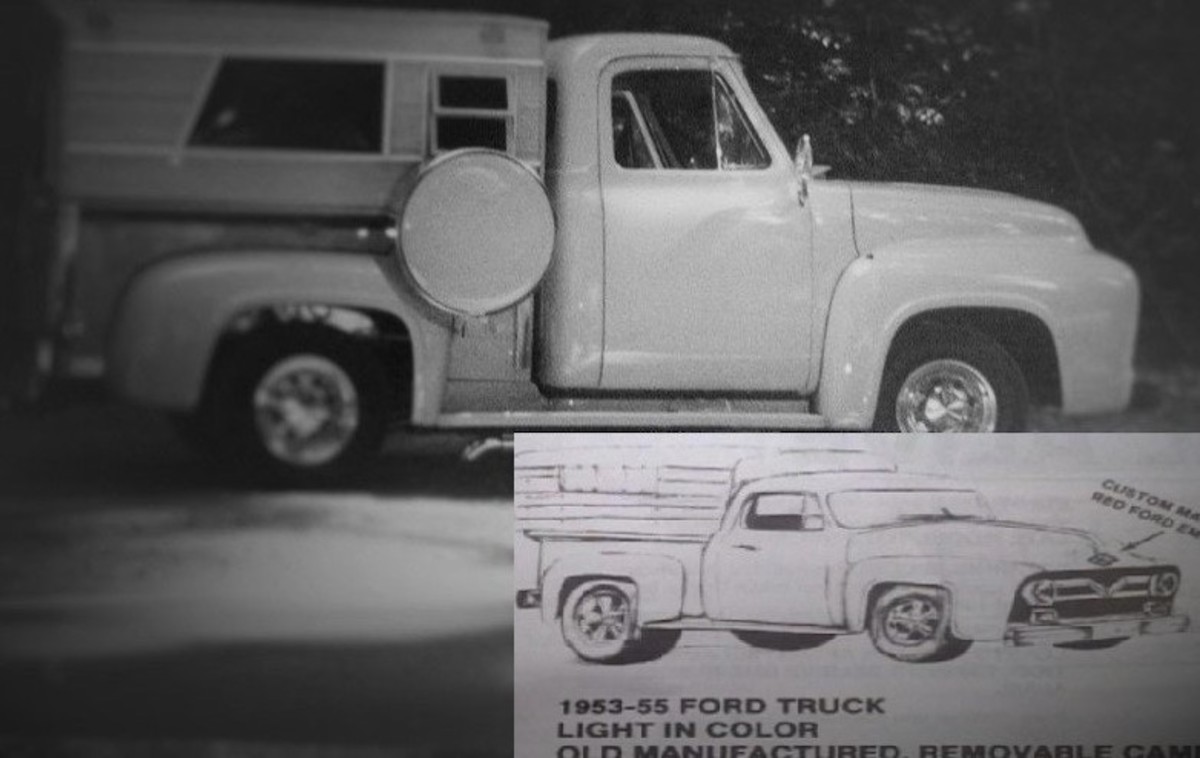

There were also reports, collected later by independent researchers, that a light coloured 1950s Ford pickup with a homemade camper shell had followed Tara on earlier rides. The truck became important later, but at the time, it was just one more worrying story in a family that already felt uneasy.

The morning she did not come home

On Tuesday 20 September 1988, Tara left home at about 9.30 a.m. She took her mother’s pink Huffy bike, a Sony Walkman and a cassette, and told Patty to come look for her if she was not back by noon because she planned to play tennis with her boyfriend at 12.30.

Multiple witnesses later reported seeing her riding along State Road 47 that morning. The last confirmed sighting placed her near mile marker 23, still on her bike. Witnesses also saw a light coloured, older style Ford pickup with a camper shell following closely behind her.

When Tara missed her noon deadline, her mother began to worry immediately. Around twelve minutes past noon she drove the route herself, scanning the roadside and ditches. She saw nothing. By mid afternoon, with no sign of her daughter, she contacted the Valencia County Sheriff’s Office to report Tara missing.

That evening and into the next day, family, friends and law enforcement searched along Highway 47. They found parts of a Sony Walkman and a cassette tape scattered along the shoulder, as if someone had dropped them while travelling fast. Tara’s mother believed her daughter might have thrown them down on purpose to mark a trail.

Searchers also reported bike tracks and possible scuff marks in the area, but these were not enough to show exactly where or how Tara had left the roadway. Her bike was never recovered, although later rumours claimed it had been found and never logged, a claim current investigators say they cannot verify.

Within days, the disappearance of a nineteen year old college student on a routine ride drew regional attention. Newspapers covered the search efforts, and community volunteers joined official teams combing the desert and mesa near the highway. None of it produced Tara.

A Polaroid in a Florida parking lot

On 15 June 1989, almost nine months after Tara vanished, a woman walked out of a convenience store in Port St Joe, Florida, and noticed a Polaroid photo lying face down on the asphalt. It was in the space where a white Toyota cargo van had just been parked.

The photo showed a young woman and a boy lying in the back of what looked like a van. Both had black tape across their mouths, and what appeared to be bindings at their wrists and ankles. A paperback copy of My Sweet Audrina by V C Andrews lay beside the woman.

Polaroid technicians later examined the film and concluded that it could not have been produced before May 1989. Whoever took the picture had done it months after Tara disappeared and hundreds of miles from New Mexico.

When a friend saw the photo on the television show A Current Affair and recognised a resemblance to Tara, she called the family. Patty travelled to Florida and studied the original picture closely. She pointed out a scar on the woman’s leg in the photo that matched one Tara had received in a car accident.

British forensic analysts at Scotland Yard examined the Polaroid and said they believed the woman could be Tara. A separate analysis by Los Alamos National Laboratory reached the opposite conclusion. The FBI examined the photo three times and kept its official position as “inconclusive.”

For Tara’s parents, the image offered a small and painful hope that she might be alive somewhere. For investigators, the Polaroid produced thousands of tips and consumed time and resources without ever giving a clear answer.

The boy in the picture and the Zuni Mountains

The boy in the Polaroid also became a case. The family of another missing New Mexico child, nine year old Michael Henley, saw the image on television and thought the boy resembled their son, who had vanished during a camping trip in April 1988.

In 1990, searchers found Michael’s remains in the Zuni Mountains about seven miles from where he had gone missing. Investigators believe he most likely died of exposure after wandering away from his family’s campsite. That finding strongly weakened the theory that the Polaroid showed both Tara and Michael.

Even after that, the photograph continued to circulate in true crime coverage and documentaries as if it remained central to Tara’s case. Modern investigators in Valencia County now describe it as a distraction that pulled attention away from more solid local leads.

Other photographs and anonymous letters

The Port St Joe Polaroid was not the only image to surface. In July 1989, another Polaroid of a young woman with tape over her mouth was found near a construction site in Montecito, California. The fabric behind her resembled the striped fabric seen in the first photo.

A third picture, taken on film manufactured in 1990, showed a woman loosely wrapped in gauze and wearing large black framed glasses in what looked like an Amtrak train seat. Tara’s mother thought the Montecito photo might show her daughter, but felt the train picture was probably a hoax.

In 2009, the police chief in Port St Joe received two anonymous letters postmarked from Albuquerque. Each contained a grainy picture of a boy with a dark band drawn over his mouth, imitating tape. A local newspaper received a third letter with the same photo.

The letters had no messages, signature or explanation. Authorities sent the photos to the FBI to check for fingerprints or DNA, but nothing useful came back. Investigators have never confirmed whether the boy in those images is the same one shown in the original Polaroid or whether any of them relate to Tara.

At the same time, a self described psychic contacted police with a story about a runaway she had met in California who might have been Tara. The caller claimed the girl had later been killed and buried there. Searches in the suggested area produced nothing.

Excavations, a legal death and a stalled case

In 1993, Tara’s family received a tip from a woman who said she had heard digging noises the day after Tara disappeared at a site several miles south of Belen. Deputies used backhoes to excavate the area but did not find human remains or evidence linked to the case.

Five years later, in 1998, a judge formally declared Tara dead and ruled the case a homicide. That ruling did not explain how she died or who was responsible. It only recognised legally what most people in the case already believed.

By the late 1990s, the investigation had slowed. Leads based on the Polaroids went nowhere. The mysterious pickup truck from the highway was never identified. Witnesses grew older and more scattered, and the case became one more unsolved file in a small sheriff’s office.

A sheriff speaks about local teenagers

In 2008, Valencia County sheriff Rene Rivera gave interviews stating that he believed he knew what had happened to Tara. According to him, several local teenagers in a truck had accidentally hit her while she rode her bike, panicked, and then killed her and hid her body.

Rivera said that Tara knew at least some of the boys. He suggested that more people helped cover up the crime and that the truck had been repaired or destroyed. He refused to name the suspects publicly and said he did not have enough physical evidence to bring charges without a body.

Tara’s stepfather, John Doel, was furious about those comments. He argued that if the sheriff truly believed he had strong suspects, he should either file charges or stay silent, and that circumstantial evidence had been enough to secure convictions in other homicide cases.

Rivera never moved the case forward. His remarks did, however, give shape to a theory many people in Belen had talked about quietly for years: that local young men, protected by powerful families and early investigative mistakes, had escaped responsibility for whatever happened on that road.

Lost evidence and questions about the original investigation

When a new team of investigators returned to the file years later, they found gaps that still frustrate them. Former detective Ray Flores told a television station that some reports from the late 1980s and early 1990s had been lost, including documents from a drug investigation at the nearby Rio Communities Motel.

Flores recalled that case because officers had found a car and a suitcase with telephone wire inside, suggesting someone had been bound at some point. He later learned that the suitcase had been destroyed, ending any chance of modern forensic tests on it.

There are also long running stories about a pink bike and underwear with the initials “T C” being found and never processed. Lieutenant Joseph Rowland, who now leads the case, says he has never seen evidence that those items were actually collected and doubts they still exist.

Rowland and Flores both reject the idea of a deliberate cover up by investigators, but they agree that record keeping, evidence handling and follow up in the first years fell short of what would be expected today. Those shortcomings left gaps that newer detectives now have to work around.

A community sleuth and a new task force

In 2013, New Mexico authorities formed a six person task force to reinvestigate Tara’s disappearance. Around the same time, Tara’s former classmate Melinda Esquibel began her own deep review of the case, collecting documents, interviewing witnesses and launching a podcast called “Vanished: The Tara Calico Story.”

Esquibel’s work kept the story in public view and encouraged more people to come forward with old memories and new tips. Investigators say her efforts produced information they could not have reached on their own, especially from people who no longer trusted law enforcement but were willing to speak to a friend of Tara’s.

In 2019, the FBI announced a reward of up to twenty thousand dollars for precise details leading to the identification or location of Tara and the arrest and conviction of those responsible. They also released an age progression image showing what she might look like in middle age.

New warrants, new suspects and a sealed file

In September 2021, the Valencia County Sheriff’s Office and New Mexico State Police revealed that they had executed a sealed search warrant at a private residence in Valencia County in connection with the case. They gave no details about the property or what they had seized.

Two years later, in June 2023, Sheriff Denise Vigil announced what she called a breakthrough. She stated that investigators now believed they had enough evidence to send the case to the Thirteenth Judicial District Attorney’s Office for review of potential charges and that they had identified specific persons of interest. Their names and the supporting affidavits remain under court seal.

Lieutenant Rowland, speaking to local media, said that his team had gone back through every file from the day Tara disappeared onward. They built new binders, compared old witness statements and re evaluated each theory. He said they believe they understand what happened and who is responsible.

Because the case dates to 1988, prosecutors must work under the laws that existed then, including limits on how long they can wait to file certain charges. They also have to rule out other suspects raised over the years, such as serial killer David Parker Ray, whose possible link was carefully checked and formally dismissed.

As of late 2025, the district attorney’s review is still in progress, and no arrests have been announced. Investigators have told reporters that they continue to follow up on additional leads while they wait for a charging decision.

A mine shaft and an unfinished search

Recent coverage has described a renewed search effort at an abandoned mine north of Belen. Reports say law enforcement set up fly traps inside the shaft to collect insects whose remains might carry traces of human decomposition, a method sometimes used when searching in confined underground spaces.

According to summaries of local reporting, no human remains have been recovered from that site so far. Authorities have not said publicly what led them to that mine, how long they plan to continue work there or how closely it connects to their current suspects.

What is clear is that, even after nearly four decades, investigators have not given up on finding Tara’s body. Both the FBI and local officers say they still consider the case active and the reward offer remains in place.

The family left behind

Tara’s family did not live to see this recent progress. Her father, David Calico, died in 2002 after he was beaten and mugged in Albuquerque. Her mother, Patty, died in 2006 from complications after a series of strokes, having moved to Florida with her husband John.

People who visited them in those years recall that they kept a bedroom ready for Tara, filled with her things. According to a 2018 feature, they continued to leave gifts and cards for her on birthdays and holidays, treating her absence as something temporary that might still end.

Her stepfather and siblings have spoken publicly about wanting one thing above all: to know what happened and to bring her home, even if that only means a grave they can visit. They have lent their support to Esquibel’s documentary work and to the continued efforts of investigators.