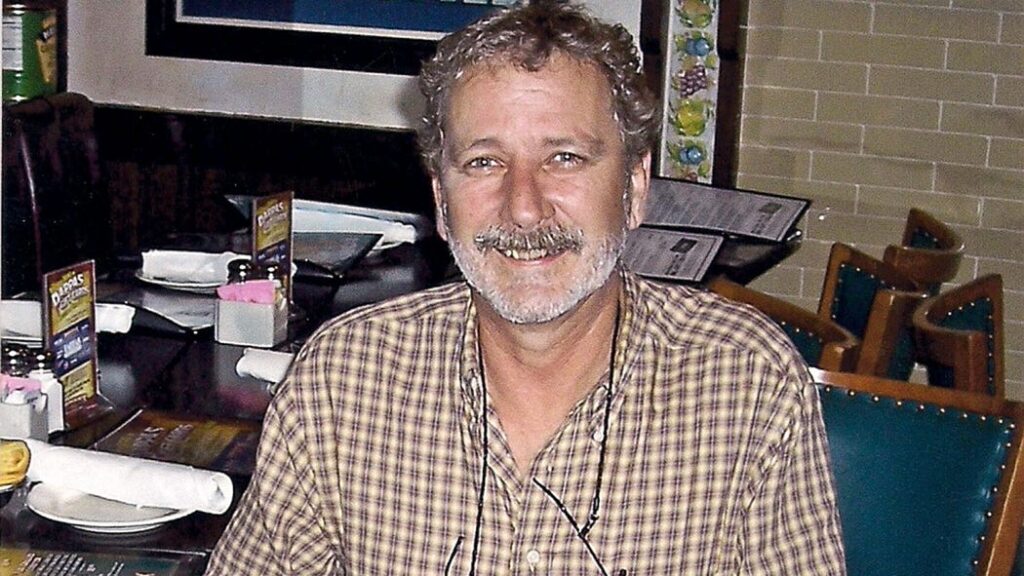

The front desk remembered him because he never caused trouble. That mattered at the MCM Eleganté. Most guests left barely a mark, but Greg Fleniken had a routine you could set your watch to.

He would check in every Monday afternoon, same room, same suitcase, same walk across the lobby. He never asked for anything extra. Just the key. Room 348 in the cabana wing. He parked his truck beneath the palms, walked past the pool, and settled into what had become a second home.

No one saw him again after that.

A Reese’s wrapper lay opened on the bed. The air inside was still and heavy. Whoever came through the door on Thursday morning said the room was warm, even humid. Not hot like a summer afternoon in Beaumont, but warm in a way that clung to your skin.

They found him lying face-down, knees awkwardly bent, one hand curled under him, two fingers clutching a spent cigarette. There was a damp spot on the front of his pajamas, a detail quietly noted and quietly dismissed. The television was still playing. The ashtray had not spilled. His boots were neatly set by the suitcase. And there was no sign of anything broken, spilled, knocked over, or out of place.

It looked like a heart attack. Or maybe a stroke.

Detective Scott Apple was sent to confirm just that. He walked through the doorway with the calm rhythm of someone who had done this too many times to count. The man on the floor wasn’t robbed. His wallet was where it should be, thick with bills. Nothing had been taken. No forced entry, no weapons in sight, no witnesses.

Just the smell of cigarette smoke, an empty root beer bottle, and a body.

The detective called it natural causes. So did the hotel manager. So did the EMTs. For a moment, even the widow did.

Greg Fleniken had smoked most of his life. He worked in the oil business. He hated doctors. He kept to himself. In some strange way, this seemed to fit.

Until it didn’t.

When the autopsy began, Dr. Tommy Brown expected to confirm the obvious. He’d seen hundreds of bodies come across his table in Jefferson County. Few stayed with him. It was routine.

This one wasn’t.

He saw bruising near the hip. Swelling in the groin. A small cut on the scrotum. Strange, but maybe from a fall. He peeled back the layers.

The internal organs told a different story.

Blood pooled in places it should not have. Greg’s intestines had ruptured. His stomach lining was torn. Two ribs were broken. His liver was bleeding. And near the heart, something else. The right atrium—burst.

A man does not break open from the inside unless something has hit him, hard.

The injuries made no sense for a man who collapsed quietly in his hotel room. There were no signs of a struggle. No evidence of a fall from height, or of being run over. The skin was intact, the face almost peaceful. But inside, it was a wreckage.

Dr. Brown had no choice. On the official form, under “Manner of Death,” he didn’t write natural causes.

He wrote homicide.

That single word sent the case lurching back to life.

A Scene Too Quiet

The word “homicide” traveled quickly. By the time it reached Detective Apple again, his inbox was full. The report from the medical examiner’s office didn’t explain what weapon had been used. It didn’t even say whether there was a weapon at all.

But it made one thing clear. Greg Fleniken had not simply died. He had been killed.

Apple went back to Room 348 and sat alone on the corner of the bed. The floor beneath him had already been cleaned. The towel Greg had used to rest his cigarette and candy was gone. The Reese’s wrapper was gone. The rug had been vacuumed. The ashtray scrubbed. There was no blood. No shell casing. No broken lamp or overturned furniture. Just silence.

It didn’t feel like a crime scene. And that was the problem.

Apple had worked the SWAT team, led entries, taken down doors. He’d seen homicides born of rage, of money, of jealousy. But this wasn’t any of those. There was nothing loud about what had happened here. It was clinical. As if the killer had slipped through the wall and back out again.

He started over. The hotel logs showed Greg had called the front desk on the evening of his death. Around 8:30, he reported a blown circuit after running the microwave. The repairman came up, reset the breaker, and left. Greg had made a joke about it, sounded sheepish. No concern in his voice. He had gone back to his movie.

The electricians next door, in Room 349, had also been affected by the outage.

There were four of them. They were in town on union work. At night, they gathered in each other’s rooms, drank beer, and talked loud. The walls were thin. They admitted to being there that night. But none of them claimed to know what had happened in the next room.

The idea of a confrontation in the hallway was floated. Maybe the men had banged on Greg’s door, angry at the power outage. Maybe they had pushed past him, maybe a fight had broken out. But there were no marks on the hallway carpet. No blood on the walls. And no one reported hearing raised voices.

That was the other thing. No one heard anything.

If Greg had been beaten to death, someone would have heard something crash. There would have been shouts. A grunt. Something.

But nothing.

Even the most basic details stopped making sense. If Greg had been hit hard enough to break bones, why were his ribs not bruised? If he’d been stomped or kicked, why hadn’t the bedding shifted? Why hadn’t the candy bar rolled off the towel?

Apple found himself circling the same questions. What had done it? And why?

He looked at Greg’s history again. The man didn’t gamble. He didn’t cheat. He didn’t borrow money. He had no enemies, no secret meetings, no ex-lovers showing up in parking lots.

He worked, drove home to Susie on the weekends, and watched superhero movies in bed.

If a crime had occurred, it had not come from outside Greg’s life. It had come from within the walls of the Eleganté.

Time passed. A reward was offered. Susie hired a private investigator out of Houston, a former FBI agent. He met with Apple, reviewed the file, and left town quietly.

That December, Apple closed the file.

Then one morning, months later, Ken Brennan picked up the phone on a golf course in Florida. It was Susie.

Brennan didn’t use a secretary. He liked answering calls himself. Susie explained the case in fragments. Her husband had died, the autopsy said murder, but nobody knew how. The police had gotten nowhere. A friend had read about Brennan in a magazine and told her to call.

“I’ll take a look,” he said.

When Susie apologized for feeling sick and not sending over the files right away, Brennan cut her off.

“Then you fuckin’ take care of yourself.”

The voice was gravel. But the words landed like a hand on the shoulder.

He asked only one thing before they hung up.

“Was your husband right-handed?”

“Yes,” she said. “Right.”

“Which hand did he smoke with?”

“The right.”

“You sure?”

“Absolutely.”

Then he hung up.

And back in Texas, he told Detective Apple, “I think I know how this guy died.”

The Hole in the Wall

Ken Brennan arrived in Beaumont with his shirts pressed and his instincts sharper than most. He didn’t pace crime scenes. He listened to them. Room 348 had already been scrubbed clean, but he asked to see the crime-scene photos anyway.

He stood inside the room for a long time.

It was quiet now, like it had been that night. The same green carpet, the same nightstand, the same wall that separated 348 from the room next door. Brennan turned toward the door, then back to the bed. He walked it out, retracing Greg’s last steps.

A cigarette in the left hand. That wasn’t right. Greg was right-handed. He smoked with his right.

Brennan played the moment over. Greg lying back in bed, watching Iron Man 2. The breaker had tripped earlier, killing the power. He called the front desk. The repairman had come and gone around 8:30. Greg must have forgotten to turn the A.C. back on. That explained the warm room.

At some point, he had lit a fresh cigarette, shifted it to his left hand, and stood up—maybe to adjust the air, maybe to answer a knock. Then something hit him. Something invisible, fast, and final. He collapsed, two steps from the bed.

Whatever it was, he never got to the door.

That made sense.

But none of it explained the injuries.

Brennan and Apple visited Dr. Brown. The coroner was firm. “This man was beaten,” he said. “That’s what killed him.”

Brennan asked about a kick. A steel-toed boot. Could that do the damage? Maybe. But it didn’t feel right. The cigarette still burned in his hand. Nothing about the room suggested a struggle.

So Brennan asked a question that hadn’t been asked before.

“What if he was shot?”

Dr. Brown said no. The body had been thoroughly examined. There were no entry wounds. No bullets. And the man had been cremated. Nothing remained.

Still, Brennan insisted they go back. He and Apple returned to Room 348 and began searching every inch. Walls, furniture, baseboards. They crawled on the floor with flashlights, checking behind tables and lamps.

Then Brennan saw something.

A small indentation on the wall near the door to Room 349. It looked like a place where a doorknob might have banged over time. But when he swung the door open, the knob didn’t line up with the dent.

He stared at it.

He and Apple stepped into the adjoining room. They asked the hotel staff to let them into 349. On the far wall, behind a nightstand, was a faint pink plug of something—about the size of a coin. Brennan touched it. Dry. Crumbly.

Toothpaste.

They chipped it away. Beneath was a perfect circle. A bullet hole.

They measured the line of fire. It matched the dent on the other side of the wall. The angle of the shot traveled cleanly through to where Greg had been sitting.

Brennan didn’t say anything at first.

Then, slowly, he stood and said,

“This motherfucker was shot.”

Back at the coroner’s office, Brennan sat across from Dr. Brown with a stack of autopsy photos between them. They went through each one, photo by photo.

“What’s this?” Brennan asked, pointing at a mark on the liver.

“Bruising,” Brown said.

“And this?”

“Intestine damage.”

He kept going. When they reached the heart, Brennan tapped the image gently.

“Doc. That’s a bullet hole.”

Brown leaned in. The photo showed the right atrium torn open. The surrounding tissue had not exploded outward, but the edges were clean.

Brown blinked. Then said,

“Yeah. That’s a bullet hole.”

He let the silence sit for a while.

Then he added, “The media is going to kill me on this.”

There was only one group of people who had been in the adjacent room at the right time.

The electricians.

Detective Apple and Brennan traveled to Wisconsin, where Tim Steinmetz now lived. The interview was casual at first. He answered all their questions, even signed a statement. Then Brennan leaned forward.

“It was, until you signed that,” he said. “Now you’ve got a problem.”

The second version of the story came quickly.

That night in Room 349, three men were drinking. Lance Mueller, Steinmetz, and Trent Pasano. Mueller had asked Pasano to fetch whiskey from his car. He also brought up his pistol. A 9mm Ruger.

Mueller began waving it around. He pointed it at Steinmetz, who dropped to the floor and cursed. Then he pointed it at Pasano.

And it went off.

There was a hole in the wall. They didn’t check next door. They didn’t knock. Mueller hid the gun in his car. Then they went to the bar.

They saw Greg’s body on a gurney the next morning. They said nothing.

Steinmetz called Mueller after the confession.

“I told them the whole story,” he said. “The guy… he died from the gunshot.”

Mueller didn’t believe it.

“They ruled it a heart attack,” he said. “There’s no way… absolutely no way… that guy was killed by a bullet.”

He kept saying it, over and over.

Until he stopped.

The Bullet Nobody Heard

Mueller refused to believe it until the detectives arrived at his door.

He called Brennan late, voice slurred, words slow. “I want to make a statement,” he said.

“You’re drunk,” Brennan replied. “Call your attorney.”

That phone call confirmed everything. The toothpaste. The angle. The silence. A bullet had traveled through drywall and struck a man watching Iron Man 2, ending his life before he could even stand up straight.

The gun had been hidden, then handed to a lawyer. The lawyer had stayed quiet. The wall had been patched with a smear of Colgate. Mueller and his coworkers had gone to the bar. Then they left town. Greg’s body was burned. For nearly a year, it had all stayed buried.

But in the courtroom in Beaumont, Texas, the facts were all on the table.

When sentencing day came, Brennan sat in the back. Susie Fleniken was there too. She had waited more than two years to say what needed to be said.

“You murdered him,” she told Mueller from the stand. “No, you didn’t intentionally seek him out to murder him. But you murdered him. With every lie you told.”

Mueller had claimed he didn’t know anyone was in the room. That he thought maybe the bullet had hit a lamp, or the carpet, or just vanished into the wall. But when he saw the body bag come out, he didn’t step forward. He had already moved the gun. He had already sealed up the wall.

He let Greg’s death become a riddle.

What stunned Brennan was how close the man had come to getting away with it. If the bullet had traveled two inches higher, it would have missed Greg entirely. If the coroner hadn’t been as thorough. If the towel on the bed had been moved. If Brennan hadn’t noticed the cigarette in the wrong hand.

So many near misses.

“I think what bothers me the most,” Susie told reporters later, “is how long it took. How long they let him stay out there, knowing.”

The judge gave Mueller 10 years. Brennan had pushed for more. He had argued that the case wasn’t an accident, it was a cover-up. Not just carelessness, but cowardice.

“If someone had checked on him—just knocked on the door,” Brennan said, “Greg might still be alive.”

The moment of death had come without warning. No scream. No noise. Just a single shot in the next room and the soft thump of a man falling to the carpet.

In a quiet courtroom, Susie said her last words to the man who had never come forward.

“You have met your match,” she said. “I would have spent the rest of my life tracking you down. And I found you.”

After the hearing, Brennan and Apple went for lunch. They didn’t talk much. There was little left to say. The puzzle had been solved. But no one in the room was celebrating.

That night, Room 348 at the MCM Eleganté was booked again.

The curtains were drawn.

The air conditioner was on.

And no one mentioned the dent in the wall.