It was one of the mysteries that gave the Uruguayan Police the most headaches, until a brilliant idea allowed the case to be solved.

José Luis Aguiar

Readers who have already turned 100 years old — who will be few — will remember the enigma that, for several weeks, surrounded the episode known as “the decapitated woman of the Rambla Wilson.”

Although one would not need to have lived a century to know the general outline of the case, because the famous crime is one of the horrifying events most often recreated in books and collections of crime chronicles.

Exactly one hundred years have passed, as of April 28, 2023, since the murder of the mysterious woman whose corpse spent several days in the morgue without anyone — neither relative nor acquaintance — missing her or reporting her absence.

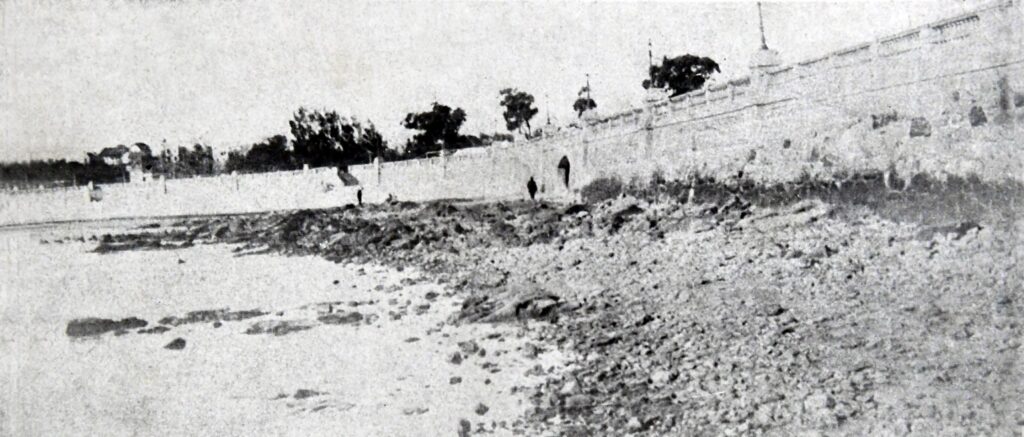

It seemed that the victim had fallen from the sky like a meteorite to lie motionless on the rocks of Montevideo’s rambla, in front of the quarries of Parque Rodó.

On May 5, 1923, the newspaper El País reported on “The mysterious tragedy of the Rambla Wilson” and asked: “Who is the decapitated woman?”

Accompanying the article was a full-body photograph of the corpse in the morgue, which was shocking not only for its gruesome nature, but because it stood out next to another social chronicle titled: “The Princess of Bourbon, passing through Buenos Aires, speaks of her current, perfectly bourgeois life.”

Such were the newspapers of the time: each page was a jumble of information.

“Everyone has heard that a few days ago a woman’s body was found among the rocks of the Rambla Wilson, near the quarries, and that she had been decapitated. The victim had head wounds caused by blows and a gash more than 10 centimeters wide, stretching from side to side of her neck.

The most impenetrable mystery surrounded the event, and up to now, despite the days that have passed and the actions of the officials under Mr. Tácito Herrera, it has not even been possible to identify the victim…,” read the article.

“She was a young woman, and although the photograph does not show it well because it was taken many hours after the body was found, the deceased’s facial features made her out to be a not unattractive little woman,” wrote the journalist, and went on to describe her: “with light olive skin, appearing to be between 22 and 24 years old, light brown hair…”

No news about the crime was published again until five days later. On May 10, under the title “The mystery of the decapitated woman of the Rambla Wilson,” the author of the article, lacking new data, padded the text with digressions such as: “The brutal murder continues to be the subject of commentary… A young woman who, despite the days passed, has not been identified… We do not blame the police for not finding the author or authors of the tragedy. The agents under Mr. Tácito Herrera have given their all in seeking to solve the crime. We know for a fact that, more than once, the majestic mustaches of the commissioner lost their musketeer line after following an unfruitful lead.”

The body, meanwhile, remained in the morgue, cleaned and clothed, in view of a parade of people who came hoping to give her a name. Among the quiet and curious crowd was a woman — María Angélica Ferraris — who did not know the deceased, although she would later play a key role.

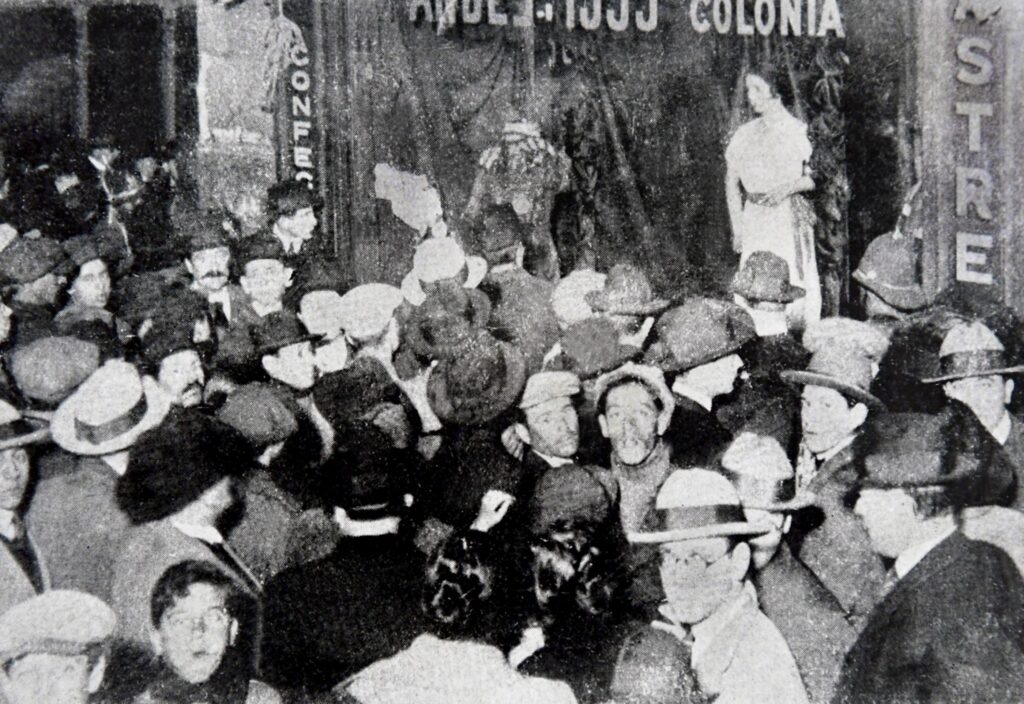

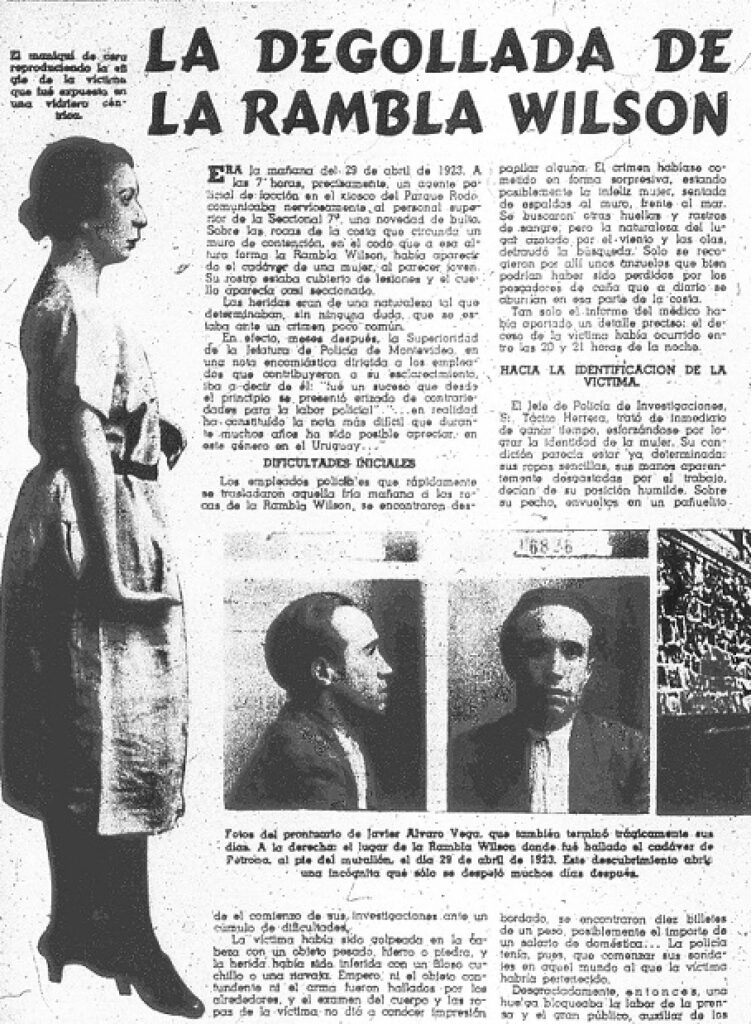

Exhibition of a mannequin of the “decapitated woman of the Rambla Wilson”

The case was a puzzle missing its central piece: the victim’s name. The police could not follow any thread because they lacked the spool. They first needed to identify the corpse.

And so, the head of Investigations came up with an original idea. He summoned a sculptor who made a mask of the woman’s face and, using that, the Ortega shop was commissioned to create a full-sized mannequin of the deceased. The first photos of the face appeared in the press on May 18.

“Today,” the report said, “the mannequin will be displayed at the headquarters of the Police of Investigations, on San José street, and in front of it the criminal elements of the underworld will be made to pass first… Tomorrow, the mannequin will be exhibited in the shop window of a central store.”

Films were also made of the wax doll and shown in all the cinemas of the country, although these efforts achieved no results.

Starting at the end of May, crowds gathered at 18 de Julio and Andes in front of the store “Al Signo Rojo,” owned by tailor Francisco Cammarano, where the mannequin of the deceased stood in the window wearing the cream-colored dress, buttoned in the back, that she wore on the day of her death.

Days passed, and just when the police were losing hope of identifying the decapitated young woman, the chief of Investigations learned that a Jewish couple of Russian origin, living at the corner of Río Branco and Mercedes, had recognized the mannequin’s clothes. Indeed, the deceased had been the domestic worker of Bernardo Litvan and his wife, and she had left their home on April 28, the afternoon of the crime.

The unknown victim now had a name: Petrona López.

A series of coincidences

When the police questioned Mrs. Litvan, she said that the resemblance of the figure to her maid Petrona was striking, but that “some differences” in the face gave her doubts.

Of course, the mannequin had makeup — painted lips, blushed cheeks, outlined eyes — that did not match her maid’s usual appearance.

Mrs. Litvan, however, was able to establish several coincidences that reinforced the police’s conviction that they were indeed dealing with the real victim. Below are some as recorded in the press:

1st coincidence: Before leaving, the young Petrona López received 10 pesos in wages at the Litvan house. That sum was paid in one-peso bills. In fact, the murdered young woman had ten one-peso bills in a handkerchief hidden in her chest.

2nd coincidence: The handkerchief, as described by Mrs. Litvan, “had a little flower embroidered in one corner”; which matched the handkerchief found on the body.

3rd coincidence: Petrona López wore, on the afternoon she left the Litvan house, a “raw silk dress with a bow,” just like the one the murdered girl had.

4th coincidence: About eight days earlier, Petrona López had had her boots repaired. The murdered woman’s shoes had a recent patch.

5th coincidence: Mrs. Litvan said the young woman “was missing some teeth.” The murdered girl had only one tooth.

6th coincidence: Petrona López liked hand-sewing; she spent all her free time at it. “This reference is important,” noted the journalist, “since the lace on the bodice, petticoat, and underwear was handmade. And considering that the fingertips of the young woman found on the Rambla Wilson had needle marks, the detail is yet another coincidence.”

And so on, until registering about twenty coincidences that confirmed that the body found on the morning of April 29 belonged to Petrona López.

Petrona as seen by her employer

Mrs. Litvan described her maid, who had worked in her home since the beginning of that year, as a silent woman: “Petrona only spoke when necessary, rarely laughed, and never sang, despite being a young and not unattractive woman.”

“When she finished her daily chores, she would go up to the attic, where she wrote letters or did crochet. She also spoke vaguely about her family, saying she was from the countryside; and it showed she was a country girl not only because of her rustic manners, but also because of her very provincial tone of speech.”

During her stay at the Litvan home, the maid received only two letters; they did not arrive by mail but by messenger. “She read the letters with great attention, but as soon as someone passed near where she was sitting, she would tuck them into her chest and continue her work.”

“On April 28, Petrona returned from an errand — she took longer than usual as she had to go to a nearby dairy to buy milk — and she told me she wanted to leave my house because she needed to get away from her job for a while. I tried to get her to explain her reasons, but I didn’t get a clear answer. Petrona left after I paid her for the month.”

“Time passed until the mannequin was put on display at 18 de Julio and Andes. One day I passed by that place with one of my children and, seeing the doll attracting a large crowd, I stopped to look. To my great surprise, I recognized the clothes Petrona wore when she left my house. But since the face was not very similar, I had my doubts. I mentioned it at home, and my husband decided we should inform the police.”

Unraveling the thread

With that essential information, the police quickly discovered who, apart from the household where she was employed, had a connection with the murdered woman.

And so, within a few days, the press reported that “the author of the barbaric crime is a blond man with a red face who had been seen almost daily with Petrona López during the time she was in service at the Litvan family’s home. Initial reports revealed that this man was seen talking animatedly with Petrona López on the morning of April 28, at the corner of Río Branco and Cerro Largo, near a dairy.”

A few days later, a woman returning from Buenos Aires who knew the victim’s family provided definitive information: the deceased’s full name was Sixta Petrona López Hormaeche, and she used both surnames interchangeably. In Argentina’s capital, before moving to Uruguay, she had married a young man named Javier Álvaro Vega.

Police officers raided a boarding house in the Aguada neighborhood where Vega lived with a concubine (because he had a lover, besides Petrona), and discovered that the pair had left in early May with two suitcases, one large leather one and one smaller “mahogany-colored” one, which matched the description of the suitcase Petrona had taken when she left her job with the Litvans. Searching the room, they also found a tram ticket from La Transatlántica, dated April 28, with a destination of Parque Rodó.

The investigation was moving smoothly until a huge thorn appeared in the path: The resurrection of Petrona López!

The police had contacted Petrona’s mother, who lived in the province of Buenos Aires, and were shocked by her response: the mother claimed to have received a letter from her daughter, dated May 10, stating that she was with her husband in the city of Santos, Brazil.

In the northern country

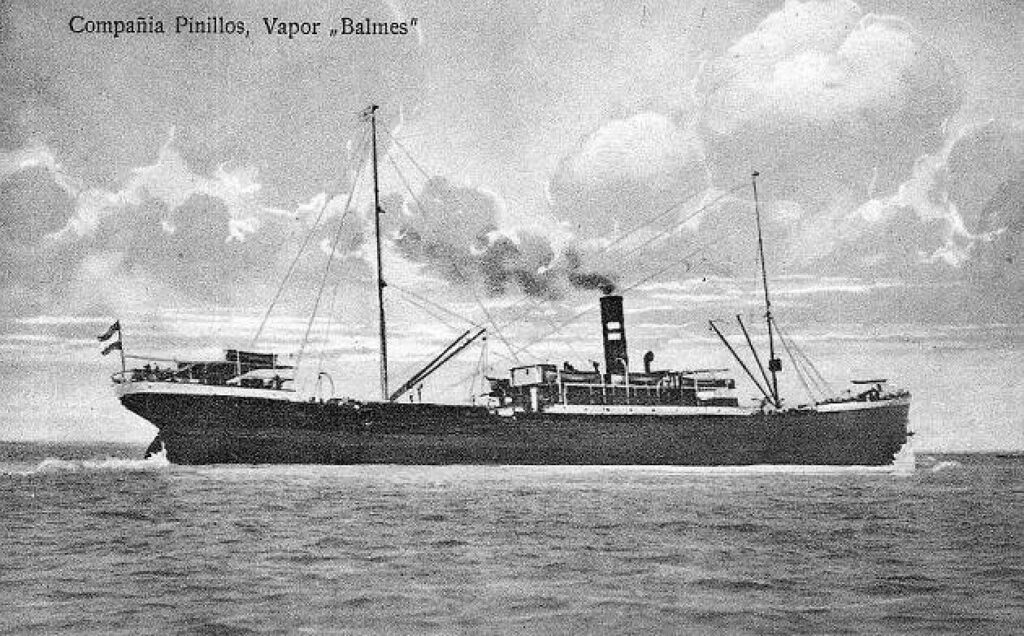

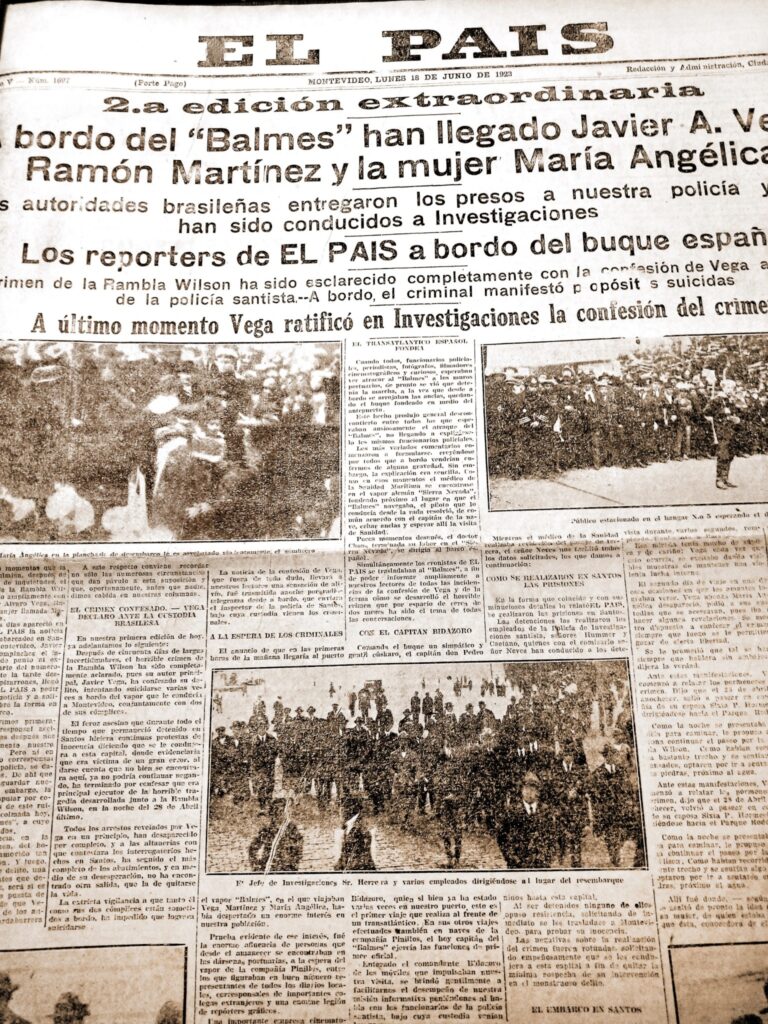

On the morning of June 18, 1923, fifty days after the first news about “the decapitated woman of the Rambla Wilson” was published, a massive crowd gathered at the docks of Montevideo’s port, awaiting the arrival of the steamer Balmes from Santos.

Numerous police officers and a legion of journalists and photographers waited at the gangway for the disembarkation of two handcuffed passengers: Javier Álvaro Vega and María Angélica Ferraris. The mystery of the domestic worker Petrona López Hormaeche had been fully solved.

The clue about the letter the victim had supposedly sent to her mother in Argentina allowed the authorities to locate Vega and his “wife,” who were living at 56 Constitución Street in the city of Santos.

When the local police arrived at that address, it was Vega himself who answered the door.

—We’d like to speak with your wife, Petrona López Hormaeche.

—She’s resting right now —Vega replied— Would you like me to go get her?

—Please do.

The police waited until Vega returned with the woman.

—No, we want to speak with this woman —said one of the investigators, showing a photo of Petrona— This is your wife, right?

Vega and the woman turned pale.

—What is your name? —they asked the supposed wife— Do you know that this man is wanted in Montevideo for the murder of his lawful wife, Petrona López?

—I don’t know anything —replied the woman, looking at Vega in shock— My name is María Angélica Ferraris.

The fake “Petrona” explained that they had crossed into Brazil as husband and wife, using a genuine marriage certificate in Vega’s possession.

Vega then explained the mystery of the letter Petrona’s mother had received from Brazil, which had been mailed several days after her death.

That letter had indeed been written and signed by Petrona López in Montevideo, but Vega had kept it without sending it.

After crossing the border on May 4 with María Angélica Ferraris, who carried false documents in the name of Petrona Hormaeche de Vega, the killer added a postscript to the original letter, indicating that they had traveled to Brazil. He mailed it from the city of Santos.

The letter

“Dear Mom and siblings: Since it’s been such a long time without hearing from you, I hope you answer my letters, because I can’t believe my previous ones have been lost, as I’ve written your address correctly… You can’t imagine how much I want to see all of you.”

“Give my regards to everyone, to my godmother and the Miñones family, and all of you receive our warmest greetings. —Petrona.”

The same letter contained the following postscript:

“Madam: You should know that, despite our wishes, it suited us much better to leave Montevideo for Santos. So now we’re in Brazil. Our address is: Constitución Street, 56, Santos. Write back soon — Javier.”

Confession on board

Once on board the Balmes, where he was held in a cabin under guard, the murderer began to unravel and eventually confessed to the crime, which he later detailed further in the presence of the Chief of the Investigative Police, Tácito Herrera.

Vega said that on April 28 at 6 in the evening, he met Petrona López at the corner of Río Branco and Uruguay, from where they headed to Parque Rodó on a La Transatlántica tram. They had agreed to go fishing at the rambla that evening. Vega carried fishing gear in hand (and a few other items in his clothing).

Once at the quarry area, on the rocks beyond the seawall, Vega said he didn’t feel like fishing. He threw the line some distance away, and they both sat facing the sea.

An intense argument broke out, ending with him threatening to leave her alone there. But soon more heated words followed. Local newspaper El País reported: “Vega, blinded by rage, pulled from his clothes a piece of iron and struck his wife several times in the head.” Then he threw the weapon into the water.

“Believing the victim was dead, the criminal thought he heard moans, like voices from beyond the grave. He then grabbed a straight razor (which he had also brought) and inflicted a deep cut across her neck.”

The unfortunate woman died around 7:30 in the evening, after night had fallen.

Vega returned to the boarding house, walking part of the way and taking a tram for the rest, heading back to the room where he would carry out the second part of his plan: fleeing to Brazil with María Angélica Ferraris.

During the interrogation, he tried to justify the murder by claiming that his disagreements with his wife were deep and that she “was bewitched.”

He claimed María Angélica was not involved: “She didn’t know my wife. She had never seen her,” and told an anecdote.

A few days after the murder, when Petrona López’s body was being displayed in the morgue for identification, María Angélica went to see it, like many people in Montevideo. She did not recognize her. That night, when she returned to the boarding house in Aguada, where she lived with Vega, he asked:

—Where were you?

—I went to see the body of the decapitated woman —she replied. Vega was alarmed:

—You went to see the corpse? Are you crazy? You’ll have nightmares!

Disembarkation and the end

Before the crowd of onlookers waiting at the port on June 18, under a cloudy sky, the figure of Javier Álvaro Vega appeared on the deck of the ship, flanked by two policemen who practically dragged him. “He appeared very dejected and lowered his head so that the gray hat he wore would hide his features,” the reporter wrote.

“He wore a gray gabardine suit and no collar. He was rather slim, and although not remarkable, his overall appearance was not unpleasant,” the report described.

As soon as he stepped onto the gangway, the spectators began shouting “murderer! murderer!” while trying unsuccessfully to break through the police cordon.

However, the loudest insults rose like a chorus when María Angélica Ferraris appeared, who not only was the lover and accomplice of the murderer but had also assumed the identity of Petrona López.

Javier Vega was sent to Miguelete Prison, and María Angélica was placed in the Asilo del Buen Pastor. But it did not end there.

Six years later, at the beginning of 1929, Vega attempted to escape after leaving Hospital Maciel, where he was being treated for a skin disease.

Taking advantage of a moment of carelessness by the soldiers and a prison guard escorting him, he launched into a desperate escape down Washington Street and only stopped when a well-aimed Mauser bullet, fired by an infantry soldier, pierced his back and shattered his heart.