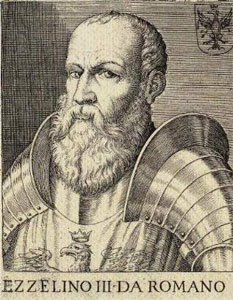

The Ezzelini family is infamous for producing some of the most notorious figures in history, and none looms larger than Ezzelino III. Picture a man so feared that his reputation rivaled that of the devil himself. Intrigued? Let’s dive into his story.

Born into power, Ezzelino showed his knack for leadership early on.

By 1223, with his father, Ezzelino II — the so-called “Monk” — retired from public life, young Ezzelino divided the family’s lands with his brother Alberico. His share?

A hefty chunk, including Bassano, Marostica, and the castles scattered across the Euganean hills.

A natural warrior, Ezzelino was tireless in battle and seemingly immune to fear or fatigue. But don’t mistake his resilience for heroism—his cruelty outpaced even the brutal norms of his era.

Ezzelino didn’t just survive; he thrived, using cunning and cold calculation to seize every opportunity. His ruthless ambition earned him command of the Ghibellines in northern Italy, a role that would cement his legacy as one of history’s most chillingly effective tyrants.

From 1225 to 1230, Ezzelino III da Romano held the titles of podestà and captain of the people in Verona, cementing his grip on power.

Even then, his reputation for ruthlessness was well-earned. One telling moment? He coldly dismissed Saint Anthony of Padua’s plea for clemency on behalf of Rizzardo di Sambonifacio. Compassion?

Not in Ezzelino’s vocabulary.

Initially, he flirted with the Lombard League but soon aligned himself with Emperor Frederick II of Swabia.

As Imperial Vicar in Lombardy, Ezzelino crushed the spirit of municipal freedom, bending northern Italy’s cities to his iron will. His reign of terror began in earnest.

In 1233, he razed Caldiero’s castle. Three years later, with Frederick II’s forces sacking Vicenza, Ezzelino took control of the city. But he wasn’t done. In 1237, he seized Padua — a city teeming with wealth and influence. His method?

Brutal efficiency. He imprisoned the elite, destroyed their properties, and conscripted the youth into his army. Distrustful of their loyalty, he eventually rounded them up, imprisoning and slaughtering as many as ten thousand.

Ezzelino’s military triumphs piled up. That same year, he crushed the Lombard Communes at Cortenuova, earning Frederick II’s favor and the hand of his daughter Selvaggia.

Tragically, she died young, adding a rare note of personal loss to Ezzelino’s otherwise relentless pursuit of power.

But his cruelty knew no bounds.

In 1242, he torched Montagnana, an Este stronghold, leaving devastation in his wake. Even after Frederick’s death in 1250, Ezzelino’s ambition burned bright.

By 1254, his unchecked power led Pope Alexander IV to excommunicate him — a desperate attempt to halt his reign of terror. But if the Church thought this would stop Ezzelino, they underestimated the man who had already defied empires and crushed cities underfoot.

By 1256, Ezzelino III’s brutal reign was finally meeting resistance.

The Archbishop of Ravenna, Filippo, enlisted Azzo VII d’Este, podestà of Ferrara, to lead a coalition against him. This new league — featuring Venice, Bologna, Mantua, the Count of San Bonifacio, and others — sought to end Ezzelino’s iron grip.

While he was preoccupied assaulting Brescia, the League managed to seize Padua. But their lack of unity kept them from solidifying their victory. Meanwhile, Ezzelino tightened his hold on Brescia by 1258, proving he wasn’t easily toppled.

In 1259, the Ghibellines of Milan summoned Ezzelino to fend off their Guelph adversaries.

Ever the strategist, he devised a plan to devastate the Lombardy countryside, lure Milan’s defenders out, and sneak into the city with the help of traitorous insiders. But this time, his cunning failed.

Betrayed, he arrived to find Milan’s gates firmly shut and the Guelph League’s army closing in. Forced to retreat, he headed toward Cassano d’Adda, only to walk into a trap.

Waiting there were Oberto II Pallavicino with Cremona’s forces and Azzo VII’s armies from Ferrara and Mantua.

A fierce battle ensued, and for the first time, Ezzelino’s invincibility shattered. Wounded and captured, he was imprisoned in Soncino. His defiance, however, remained intact.

Refusing both sacraments and medical treatment, he succumbed to septicemia on September 27, 1259, at the age of 65. His end was as grim and unyielding as his life.

As for his burial? It’s shrouded in mystery.

Initially interred in Soncino, his tomb’s exact location became a puzzle. Emperor Henry IV reportedly visited it in 1311, but after that, it vanished.

A tombstone linked to him may have been stored in the town hall during a restoration, but the ark disappeared. Perhaps fittingly, the man who left a trail of destruction behind him also left behind an enduring enigma.

Ezzelino III da Romano’s legacy is as twisted as it is fascinating.

On one hand, he’s immortalized as “feared more than the devil,” a figure whose cruelty was unparalleled. But history isn’t that simple, is it?

Alongside his brutality, many chroniclers also highlight his sharp political mind and military genius. A tyrant, yes, but also a tactician capable of shaping northern Italy’s history.

His reputation was polarizing, drawing both fear and disdain. Chroniclers of his time painted vivid pictures of his rule. Rolandino da Padova penned a detailed history of the Ezzelino years, presenting it in Padua in 1262, just a few years after Ezzelino’s death.

Dante Alighieri wasn’t about to let his notoriety slide either — he placed Ezzelino in the twelfth canto of the Inferno, cementing his place in literary infamy.

Albertino Mussato, a Padovan contemporary of Dante, went even further, dedicating a tragedy, Eccerinide, to Ezzelino’s dark tale.

He wasn’t just a man of his time — he became a legend, a subject for storytellers, poets, and historians alike. The question is, was he a devil in human form or simply a man who mastered the harsh rules of his violent era?