WARNING: This story includes crime scene photos that some readers may find disturbing.

![Who Killed Marilyn Sheppard? Ohio's Most Enduring Murder Mystery [Part Two] by JT Townsend Who killed Marilyn Sheppard cover image](https://www.crimetraveller.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Who-killed-Marilyn-Sheppard-Part-Two-696x388.jpg)

At 5:45 in the morning on July 4, 1954, Dr. Sam Sheppard picked up the phone in his lakefront home and called his neighbor. “My God, Spence, get over here quick. I think they’ve killed Marilyn,” he said. The man on the other end of the line was Spencer Houk, the mayor of Bay Village and a close family friend.

The Sheppard home stood on Lake Road, perched high above the shoreline of Lake Erie, in a quiet, middle-class neighborhood lined with large houses and manicured gardens. It was the kind of place where nothing ever happened. That morning, something had.

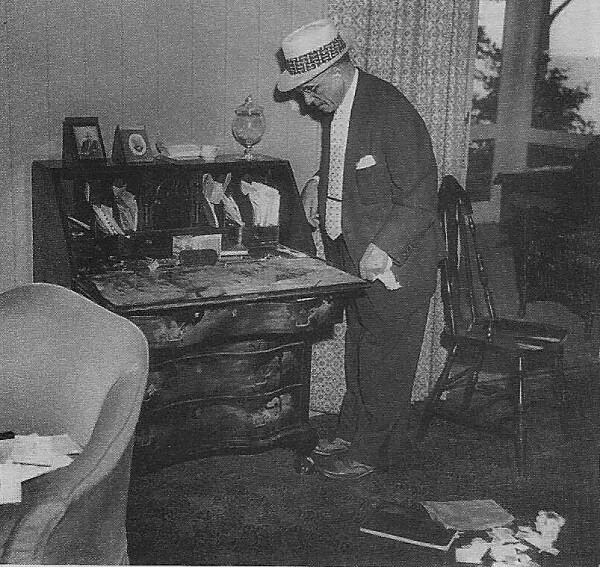

When police arrived, they found Dr. Sheppard in his study. He was shirtless and unsteady on his feet, his speech fragmented, his appearance pale and dazed. The downstairs rooms showed signs of disarray. A few drawers had been pulled open. His medical bag had been tipped over. Two of his athletic trophies lay shattered near the desk.

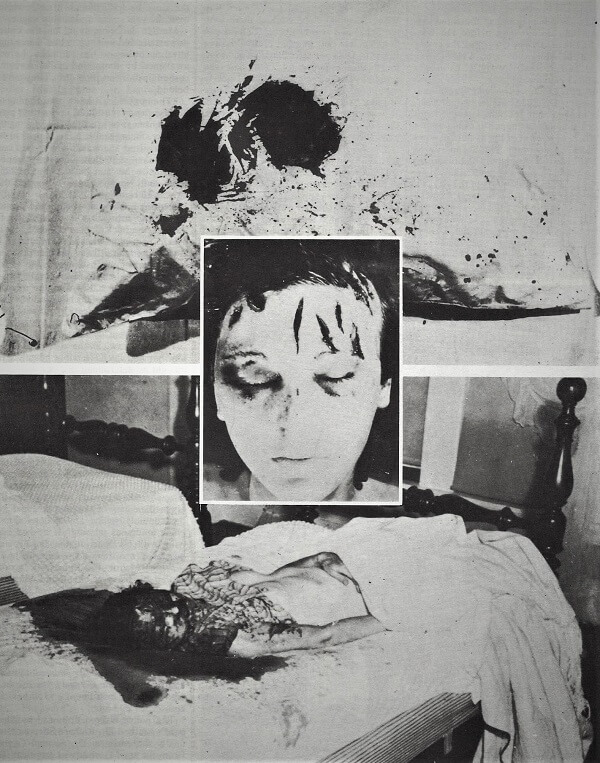

Upstairs, officers stepped into a scene that several of them later said would never leave their minds. Marilyn Sheppard, age thirty-one and pregnant with her second child, was lying in bed with her head turned to one side. Her face had been bludgeoned until it no longer resembled a face. Her upper body was exposed. Blood had soaked into the mattress and was smeared on the floor and walls. One of her teeth had come loose and landed near the closet. The headboard had marks that looked like dents.

Dr. Sheppard told officers he had fallen asleep on a couch in the living room. Sometime in the night, he said, he heard Marilyn calling his name. He ran upstairs and saw a figure in white standing over her in the darkness. Before he could reach the bed, something hit him from behind. He remembered very little after that.

He said he regained consciousness, found Marilyn unresponsive, then heard footsteps moving through the house. Looking out the door, he saw a man running toward the back exit that led to the beach. He chased him across the yard, tackled him in the sand, and lost consciousness again during the struggle. When he woke up, his legs were partly in the water. He went back into the house, checked on his sleeping son, then called Spencer Houk.

To the Bay Village police, the account was hard to believe. They had not seen forced entry. The mess downstairs looked too deliberate. The idea that a stranger entered the house, left no trail, and knocked out the homeowner twice without being seen by anyone else did not make much sense to them. It made even less sense when Sam’s brothers arrived, took him to their private clinic, and refused to allow outside doctors to examine his injuries.

Before the crime scene could be processed properly, neighbors, friends, and members of the press were already moving in and out of the house. No one controlled access. No one preserved the space.

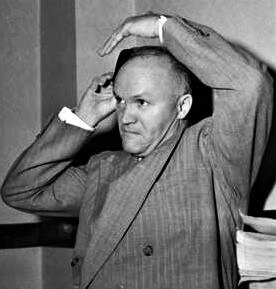

Then Samuel Gerber, the county coroner, stepped in.

Gerber was well known in Cleveland. He was sharp, confident, and had a habit of making strong early conclusions. His professional relationship with the Sheppard family had been tense for years. In the weeks before the murder, he had reportedly told an intern he planned to expose them one day. When he arrived at the Lake Road home, he quickly decided that the scene had been staged.

He noted that some items had been moved but not taken. The medical bag had been emptied, and two of Sam’s trophies had been smashed. A bag of jewelry and personal belongings had been found downstairs, not far from the stairwell. Gerber dismissed these details as part of a cover-up. In his view, there had been no intruder.

He believed the blood trail from the bedroom showed Marilyn’s blood dripping from the killer’s weapon. He said the killer had arranged the body to appear sexually assaulted in order to throw off investigators. Even without laboratory testing or crime scene reconstruction, Gerber declared that the murder weapon was likely a surgical tool, possibly one belonging to Dr. Sheppard.

Within hours of the murder, the case had already begun to shift. The narrative forming in the local press was not about a home invasion, but about a husband who wanted out of his marriage. That tone was about to harden.

Trial by Headlines

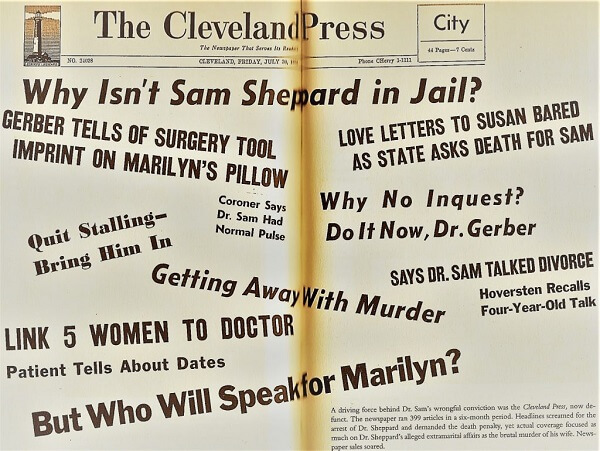

In the days following Marilyn Sheppard’s murder, the case left the confines of Bay Village and spread through Ohio’s newspapers like wildfire. The Cleveland Press took the lead. Its editor, Louis Seltzer, used front pages to raise doubt about Dr. Sheppard’s story. Each day brought a new headline, each one louder than the last.

Some articles pressed police to act. Others accused the Sheppard family of using their medical connections to shield Sam from scrutiny. The editorials adopted the voice of a town betrayed, and they spoke directly to investigators. “Quit stalling,” one headline read. “Bring him in.”

At first, the investigation stalled. The evidence did not point clearly to anyone. There was no murder weapon. No fingerprints matched a stranger. No footprints led away from the house. But when rumors of an affair between Sam and a lab technician reached the coroner’s office, the tone of the investigation changed.

Coroner Gerber called a public inquest and decided to hold it in a high school gymnasium. Folding chairs were arranged in rows. Reporters, townspeople, and neighbors took their seats. Sam Sheppard sat at a long table wearing dark glasses and a stiff neck brace. He answered each question with careful words, stating again that an intruder had killed Marilyn.

When asked about his marriage, he called it loving. When asked if he had been unfaithful, he denied it. That denial collapsed almost immediately.

Susan Hayes, a young technician who had worked with Sam, came forward with a confession. She spoke about a long romantic relationship with Dr. Sheppard and explained that their connection had continued even after she moved out of state. Her account confirmed what many had suspected, and her composure in the face of the cameras added weight to her words.

Once the affair was public, the local press leaned harder into the story. The idea of a respected doctor with a secret life captured readers’ attention. Soon, gossip turned to accusation.

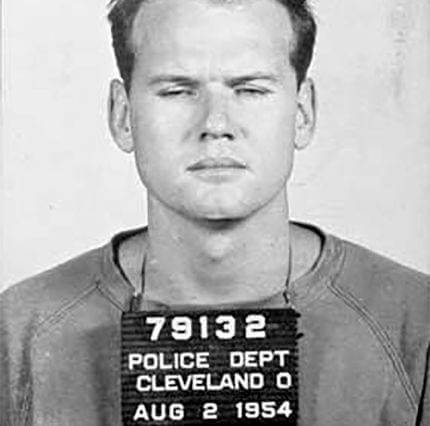

Police arrested Sam Sheppard on July 30, less than four weeks after the murder. He was taken into custody and held without bail. As he entered the jail, cameras followed closely. The crowd outside the courthouse was quiet but thick. The image of the handcuffed doctor filled the front page of every Cleveland paper that weekend.

The trial began on October 18, 1954, in Cleveland. It took place in a courtroom crowded with journalists and spectators. The judge, Edward Blythin, did not move the proceedings to a different location, even though much of the jury pool had already read months of coverage filled with speculation and pointed questions about Sam’s character. According to later reports, Judge Blythin had told a journalist before the trial began that he believed Sam was guilty.

Each day, reporters sat just behind the attorneys, close enough to hear whispered conversations. Their dispatches shaped public opinion as the trial unfolded. Onlookers arrived early to find a seat.

The state’s case rested on motive and assumption. Prosecutors said the affair had fractured Sam’s marriage. They claimed he had grown tired of Marilyn and lashed out during an argument. There were no witnesses. No confession. The prosecution presented no murder weapon. What they had was testimony about the Sheppards’ home life, a timeline that left room for suspicion, and a collection of stains and smudges they could not fully explain.

Coroner Gerber returned to the stand. He repeated his earlier opinion that a surgical instrument had caused Marilyn’s wounds. He offered no specific example of the tool. He did not submit any similar instrument for the jury to inspect. When asked how he arrived at this conclusion, he described the shape and depth of the wounds, then said he had consulted colleagues and searched the country for a match.

That claim went unchallenged. Jurors took his expertise seriously.

Sam Sheppard testified in his own defense. He described the night of the murder as he always had. He recalled falling asleep on the couch, hearing Marilyn call out, running upstairs, and then seeing a figure in white. He spoke softly. When pressed on details, he said, “I don’t know,” more than one hundred times. His account did not change, but his delivery seemed flat. Some jurors later described him as evasive.

On December 21, the jury returned with a verdict. Sam Sheppard was found guilty of second-degree murder. He received a life sentence.

The Cleveland Press published its approval in a final headline. In the city, many considered the case closed. Outside Ohio, a different conversation had begun. Reporters from national outlets raised concerns about the fairness of the trial. They noted the absence of physical evidence. They pointed out that the judge had allowed intense media coverage inside the courtroom. They asked whether a man could truly receive a fair trial while standing in the middle of a storm.

By the time Sam Sheppard entered prison, questions about the trial had already started gathering speed. Over the next ten years, the case would shift from a local scandal into a national legal controversy, and Sam’s life behind bars would become the next stage of an unresolved mystery.

The Fight to Undo a Verdict

Sam Sheppard began serving his sentence at the Ohio State Penitentiary in 1955. His conviction brought a sense of resolution to the state, but for those closest to him, the outcome felt incomplete. Within months, his legal team started pushing back. Appeals were filed, and questions about the original trial began to surface. Still, the conviction held.

What broke the impasse came from an unexpected source. Dr. Paul Leland Kirk, a professor at the University of California and one of the country’s leading forensic scientists, reviewed the case in detail. He had not been allowed to inspect the crime scene before the first trial. Now, with delayed access, he examined blood patterns, wound evidence, and room layout. His conclusion was both precise and jarring.

Kirk found that the blood trail leading away from Marilyn’s body came from someone who had been bleeding from an open wound. That blood, once believed to be hers, carried oxygen levels that showed it came from a living person with an active circulatory system. Sam Sheppard, according to medical records, had no such wound.

Kirk also noted that Marilyn had likely bitten the killer, as two of her teeth had broken on impact. Sam had no bite marks on his hands or arms. The pattern of cast-off blood on the closet door revealed an outline of the killer’s body blocking spatter, yet Sam’s clothing showed only a small stain on the waistband of his trousers.

These findings formed the basis of a new appeal, but courts remained unconvinced. Sam stayed in prison. His health declined, and he developed symptoms of deep depression. Still, the new evidence continued to gain attention.

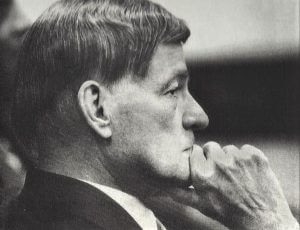

In 1964, attorney F. Lee Bailey took over the case. At the time, Bailey was a young defense lawyer with a sharp memory and an appetite for cases that challenged courtroom standards. He reviewed the records, studied the transcripts, and quickly focused on the climate surrounding the first trial. The media influence, Bailey argued, had made it impossible for Sam to receive an impartial verdict.

Bailey filed a petition in federal court, and after months of hearings, a judge agreed. In July 1964, ten years after the murder, Sam Sheppard’s conviction was overturned. The court found that his right to due process had been violated and that the original trial had become a public spectacle. Prosecutors were given sixty days to retry him or drop the case entirely.

The state chose to proceed. The retrial began in October 1966. This time, the press was restrained. Courtroom access was limited, and the proceedings unfolded in a quieter setting. Sam did not take the stand. Neither did Susan Hayes.

F. Lee Bailey focused on dismantling the credibility of the original case, starting with the coroner. When Samuel Gerber took the stand once again and claimed that the wounds had been made by a surgical tool, Bailey asked him to name the instrument. Gerber replied that he had searched the country for one but had not found it. Bailey repeated the line, then paused. “So, you are testifying about an object you have never seen and cannot describe?”

The jury listened closely. In contrast to the confusion of the first trial, the second felt structured and methodical. Bailey stayed focused on the lack of physical evidence. He emphasized the contaminated crime scene, the reliance on assumption, and the absence of any concrete link tying Sam to the murder itself.

On November 16, the jury returned its decision. Sam Sheppard was acquitted.

Freedom came at a cost. Sam had spent nearly ten years in prison. His medical license had been revoked. His reputation, once sterling, had eroded under the weight of years of speculation. He attempted to return to medicine but struggled to regain trust. Later, he turned briefly to professional wrestling under the name “Killer Sheppard.” The career shift attracted headlines, but little stability.

In 1970, Sam Sheppard died at the age of forty-six. The official cause was liver failure, though many close to him attributed the decline to alcohol and years of personal collapse. Throughout his life, he maintained that he had not killed Marilyn.

The Others in the Room

After Sam Sheppard’s acquittal in 1966, the case entered a new phase. His supporters pointed to the absence of physical evidence tying him to the crime, but that raised another question. If not Sam, then who? Over time, several names came up. Some had been close to the family. Others seemed to arrive from nowhere, only to vanish again just as quickly.

Each left a mark on the story.

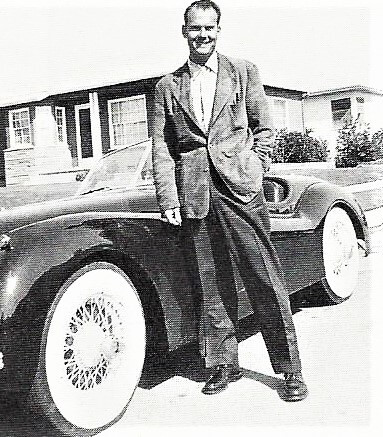

Richard Eberling

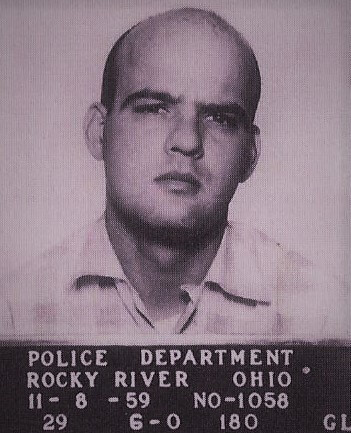

Eberling worked as a handyman and window washer in Bay Village. He had access to the Sheppard home and knew the layout. He also had a criminal history that became more concerning over time. In 1959, police arrested him for a series of burglaries. During a search of his home, they found two rings that had belonged to Marilyn Sheppard.

When questioned, Eberling volunteered that he had once cut his hand and bled in the Sheppard house just before the murder. The timeline matched. So did the presence of an unidentified third blood type found at the crime scene. Eberling agreed to a polygraph and passed it, but later reviews of the test results were mixed.

Eberling later became the caretaker for a wealthy widow named Ethel Durkin. Over the next two decades, people close to her began to die. A nurse who worked with Eberling died in a car crash. Durkin’s two sisters died suddenly after raising concerns about him. In 1984, Durkin herself fell at home and died in the hospital weeks later. Her will, which left everything to Eberling, was ruled a forgery.

In 1989, he was convicted of her murder. While in prison, he made repeated cryptic statements about the Sheppard case. Several people claimed he had confessed, although no new charges were filed.

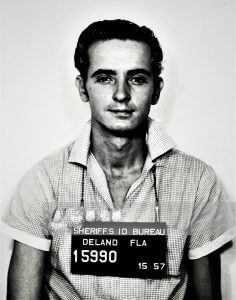

Donald Wedler

In 1957, a Florida inmate named Donald Wedler confessed to the murder of Marilyn Sheppard. He said he had been in Cleveland on the night of July 3, 1954, after using heroin with a group of people downtown. He told authorities that he had wandered into the suburbs looking for a house to rob. The house he described matched the Sheppard residence. He said he found a man sleeping on the couch, entered the bedroom, and struck the woman several times with a metal pipe when she woke up.

He claimed he fought the man upstairs, then ran toward the lake. Witnesses confirmed that he had been in Cleveland that week, and his appearance matched Sam’s description of the intruder.

Despite these details, coroner Gerber dismissed the confession and blocked efforts to give Wedler a polygraph. He also opposed a similar test for Sam. The confession was filed away. Wedler never faced charges.

Lester Hoversten

Dr. Hoversten had been a longtime friend of Sam Sheppard. He arrived in town two days before the murder and stayed overnight in the Sheppard house. He was in the middle of a difficult job search and had confided to friends that he felt stranded. At trial, he testified for the prosecution. He claimed that Sam had considered divorcing Marilyn, although other witnesses disputed this.

Hoversten had known Sam since medical school, and they had remained close. Some believed he had grown resentful of Marilyn. Others thought he wanted to rekindle the freedom he had once shared with Sam. He had encouraged Sam to leave the marriage, and some found his behavior after the murder odd. Still, he had an alibi. Multiple people placed him in Kent, Ohio, about fifty miles away, on the night of July 3.

He was never charged. He died without offering any further public comment.

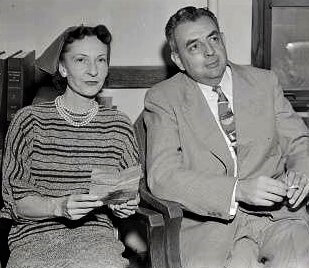

Spencer and Evelyn Houk

The Sheppards’ neighbors had been among the first people on the scene. Spencer Houk, the mayor of Bay Village, received Sam’s phone call that morning. When he arrived, he found Sam in shock and called the police. He and his wife Evelyn lived just a few houses down, and both had known the Sheppards well.

Rumors spread in the weeks after the murder that Spencer had been romantically involved with Marilyn. Some neighbors claimed his car had been seen in their driveway when Sam was away. Others speculated that Evelyn had grown resentful of Marilyn and her appearance. Over time, people in Bay Village noticed that the Sheppards had started pulling away from the Houks.

During the 1966 retrial, F. Lee Bailey hinted at the possibility that the Houks were involved. He pointed out that Sam’s attacker had struck from behind, and that the strength required to fracture Marilyn’s skull might have come from two people acting together. In one scenario, Spencer visits Marilyn, Evelyn follows, and a confrontation turns violent.

Both Houks denied any involvement. They were never formally investigated. They divorced years later.

The Case That Wouldn’t Close

More than thirty years after Sam Sheppard died, the fight to clear his name moved into a new courtroom. His son, Sam Reese Sheppard, brought a wrongful imprisonment lawsuit against the state of Ohio in 1999. He argued that his father had been falsely convicted and that the years spent in prison had ruined not just one life, but an entire family.

The case centered on DNA. Technology had changed. Forensic testing was now far more precise, and investigators had preserved enough biological material to analyze blood and semen samples from the crime scene. A forensic team compared those samples to profiles from Marilyn and Sam. What emerged was consistent with what Paul Kirk had suggested decades earlier.

Several blood spots in the bedroom did not belong to either of them.

The semen sample found on Marilyn’s body also came from an unknown male. The presence of that material aligned with early observations made by Gerber, but this time the interpretation differed. Prosecutors in 1954 had framed it as a staged scene. Forensic scientists in 1999 treated it as evidence of a possible sexual assault.

Still, the case faced a difficult standard. The burden rested on the Sheppard family to prove that Sam had not killed Marilyn. It was not enough to create doubt. They needed to show clear, compelling proof that someone else had committed the crime. That standard left little room for ambiguity, and the jury ruled against the family.

Some experts questioned the way the trial had been structured. Others pointed to how the original investigation had compromised key evidence. By the time modern science entered the picture, the physical scene had already been altered by foot traffic, missed documentation, and broken chains of custody.

The most haunting detail came from the original crime scene photographs. One image showed a clean outline on the closet door, where blood spatter had landed around the shape of a human body. Whoever stood there had blocked the blood from reaching the wood, leaving a clear absence. Sam Sheppard had no such imprint on his clothing, nor any evidence that he had stood in that position.

Even after the trial ended, questions remained. Police had never charged anyone else. The state continued to stand by the original conviction, even after it was overturned. Public interest had faded, but the facts had not changed.

At its core, the Sheppard case still sits in a narrow space between theory and proof. Sam’s version of events stayed the same from the first hour until his death. His injuries, recorded by doctors and captured in early photographs, were consistent with a physical struggle. The crime scene showed evidence of another person’s blood and DNA. The list of alternate suspects included a convicted murderer who once admitted to bleeding in the house.

No final answers have emerged. The case is part of legal history now, studied in textbooks and cited in law school lectures about media influence, due process, and the need for impartial trials. It raised the standard for pretrial publicity and helped shape how modern courts handle high-profile defendants.

For Sam Reese Sheppard, the matter never felt academic. It was about what happened in his home, to his parents, and to the version of his childhood that was lost in a single morning.

Today, the house on Lake Road is still standing. The questions inside it remain untouched.