On the morning of January 29, 1979, students arrived at Grover Cleveland Elementary School in San Diego, ready for another day of class. Principal Burton Wragg stood outside, greeting children as they filed in. Then, the gunfire started.

Bullets tore through the schoolyard. A police officer collapsed, hit by a round. Children screamed and ran for cover. Principal Wragg and custodian Mike Suchar rushed to help the wounded. Neither survived. By the time the shooting stopped, eight children and a police officer lay injured.

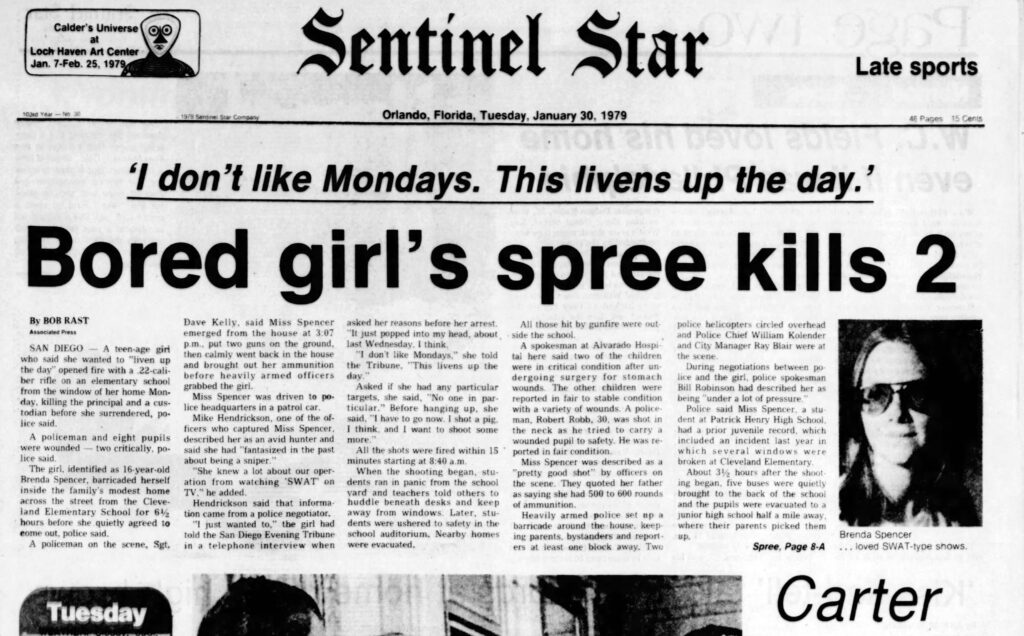

The shooter never stepped foot on campus. Sixteen-year-old Brenda Spencer sat inside her home across the street, aiming a rifle out of her bedroom window. When a reporter called her mid-siege and asked why she did it, her answer stunned the world: “I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.”

Authorities arrested her hours later. Courts charged her as an adult. She pleaded guilty to murder and assault, receiving a life sentence with the possibility of parole after 25 years. As of 2025, she remains in prison.

Many call Spencer the first modern school shooter in the United States. Some see her as a symbol of evil. Others believe she was a neglected and mentally unstable teenager who never got the help she needed. But who was she before that morning? And what drove her to open fire on a school?

Who Was Brenda Spencer?

Brenda Ann Spencer entered the world on April 3, 1962, the youngest of three children born to Dorothy and Wallace Spencer. Their marriage, once stable, shattered when Dorothy discovered Wallace’s infidelity. In January 1972, she filed for divorce, leaving Brenda caught between two parents who had little left for her.

After the split, Brenda lived with her father in conditions that bordered on neglect. They slept on a single mattress on the living room floor, surrounded by empty liquor bottles. Her mother remained distant. At parole hearings years later, Brenda accused her father of sexual abuse and her mother of complete abandonment. Both denied the claims.

She grew up across the street from Grover Cleveland Elementary School, a small girl with striking red hair who rarely fit in. At 5’2″, she seemed unthreatening, but those who knew her saw the warning signs. She hated police officers, calling them “pigs” and openly celebrating when they died. She spoke about wanting to be on TV. And she had a fascination with violence.

Despite showing promise as a photographer; once winning first place in a Humane Society competition, she had little interest in school. At Patrick Henry High School, teachers frequently had to check if she was awake. Classmates called her “crazy.” Some feared her.

By early 1978, Spencer’s life spiraled further. A facility for troubled students flagged her as suicidal. That summer, she was arrested for burglary and suspected of shooting out the windows of Grover Cleveland Elementary with a BB gun. Though police reports never confirmed the BB gun story, it became another thread in the growing pattern of her destructive behavior.

In December, her probation officer ordered a psychiatric evaluation. The results were clear: Spencer needed hospitalization for depression. But her father refused.

Instead, he gave her a gift.

On Christmas morning, 16-year-old Brenda unwrapped a Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic .22 caliber rifle with a telescopic sight. Along with it? 500 rounds of ammunition.

“I asked for a radio,” she later said. “And I got a rifle.”

When asked why her father would give her a gun despite knowing she was suicidal, Spencer’s answer was chilling:

“He bought the rifle so I would kill myself.”

What Happened on the Morning of the Shooting?

Monday, January 29, 1979, started like any other school day. Children stood outside Grover Cleveland Elementary, waiting for the gates to open. Principal Burton Wragg, 53, greeted them as he always did. Then, the shots rang out.

From her house across the street, 16-year-old Brenda Spencer took aim. Her first target? Nine-year-old Cam Miller. She later admitted she picked him because he wore blue, her favorite color. The bullet hit him. More shots followed.

Students screamed and ran, but Spencer kept firing. She struck eight children before turning her rifle toward the adults. Wragg and teacher Daryl Barnes rushed to help the wounded. Spencer shot Wragg dead before he reached them. Then she aimed at 56-year-old custodian Mike Suchar, who tried to pull a student to safety. He never got the chance.

A call for help brought police to the scene. Officer Robert Robb, 28, arrived first. Spencer shot him in the neck.

She had no intention of stopping. But then, something unexpected happened.

Police maneuvered a garbage truck in front of the school entrance, blocking her line of sight. With her targets hidden, she stopped firing. In total, she had squeezed the trigger 36 times.

Then, she barricaded herself inside.

What Did Spencer Say During the Standoff?

As police surrounded her home, Spencer refused to come out. She stayed on the phone with negotiators and, at one point, even spoke to a reporter from The Evening Tribune. When asked why she had shot at the school, her answer stunned the world:

“I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.”

She showed no remorse. She described the children and staff she had shot as “easy targets” and warned that she planned to “come out shooting.” Officers prepared for a violent confrontation.

But in the end, it never came.

After several hours, Spencer surrendered. Some reports claimed she only gave up after negotiators promised her a Burger King meal. Regardless of the reason, she walked out of the house and into police custody.

What Happened to Brenda Spencer After Her Arrest?

Authorities charged Spencer as an adult. She pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and assault with a deadly weapon. On April 4, 1980; one day after her 18th birthday, a judge sentenced her to 25 years to life in prison. Prosecutors had also filed nine counts of attempted murder, but the court dismissed them.

Prison doctors later diagnosed Spencer with epilepsy and depression. She received medication for both while serving time at the California Institution for Women in Chino. There, she worked repairing electronic equipment.

Under the terms of her sentencing, she became eligible for parole in 1993.

At her first parole hearing, she changed her story. She claimed she had been suicidal and hoped police would kill her. She also alleged she had been using alcohol and drugs at the time of the shooting. But toxicology tests from the day of her arrest contradicted her claims. She had no drugs or alcohol in her system.

As the years passed, her accounts grew more troubling. At her 2001 parole hearing, she accused her father of physically and sexually abusing her. He denied the allegations. The parole board found her claims suspicious, noting she had never mentioned them before.

By 2005, her mental health became a focal point. Prosecutors argued she was still too dangerous to be released, citing a self-harm incident from 2001. Spencer had carved words into her own skin. Early reports claimed the words read “courage” and “pride.” At her parole hearing, she corrected them: the real words were “unforgiven” and “alone.”

The board denied her parole again in 2009, ruling she would have to wait ten more years for another hearing.

In August 2022, she and the Board of Parole Hearings agreed she was still unsuitable for release. She remains incarcerated at the California Institution for Women. Her next chance at parole will come in 2025.

How Did the Cleveland Elementary School Shooting Change America?

In the aftermath of the shooting, the city of San Diego tried to move forward. Officials installed a plaque and flagpole at Grover Cleveland Elementary to honor the victims. But the school itself did not survive.

By 1983, declining enrollment forced the city to shut down a dozen schools, including Cleveland Elementary. Over the next few decades, the building housed various charter and private schools. From 2005 to 2017, it became the Magnolia Science Academy, a middle school for grades six through eight. Then, in 2018, the school was demolished to make way for a housing development. The memorial plaque was relocated to a street corner where the school once stood.

But the tragedy did not end there.

One of Brenda Spencer’s first cellmates, a 17-year-old girl, formed a disturbing connection with Spencer’s father. She moved in with him, married him in 1980, and had a daughter. Eventually, she fled the marriage and divorced him, leaving Wallace Spencer to raise their child alone. He died in 2016.

Then, almost exactly ten years after Brenda Spencer opened fire, another shooting happened at a school with the same name.

On January 17, 1989, a gunman attacked Grover Cleveland Elementary in Stockton, California. This time, the toll was even higher – five students died, and thirty others suffered injuries. Christy Buell, a survivor of the 1979 shooting, spoke for many when she saw the news.

“Shocked. Saddened. Horrified.”

The school shooting epidemic had begun. And for many, Brenda Spencer had lit the fuse.

How Did the Media Cover the Cleveland Elementary Shooting?

Brenda Spencer’s crime shocked the nation, but it was one sentence that made her infamous. “I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.”

Those words traveled fast, making headlines across the country. Among those who read them was Bob Geldof, the lead singer of The Boomtown Rats. At the time, he was in Atlanta, where a telex machine at WRAS-FM, Georgia State University’s campus radio station, printed out a news story about the shooting. Geldof couldn’t believe what he was reading. The sheer detachment in Spencer’s statement haunted him.

Inspired, or perhaps disturbed, he wrote a song: “I Don’t Like Mondays.”

The song was released in July 1979 and became an instant hit. It held the number one spot in the UK for four weeks and became The Boomtown Rats’ biggest success in Ireland. In the U.S., it never broke the Top 40, but it still received heavy radio airplay everywhere except San Diego. The Spencer family tried to block its release, but the song spread regardless.

Years later, Geldof revealed a chilling detail. According to him, Brenda Spencer had written to him from prison.

“She was glad she’d done it because I’d made her famous,” he claimed. “Which is not a good thing to live with.”

Spencer, however, denies ever contacting him.

How Has the Cleveland Elementary Shooting Been Portrayed in Film and Television?

The shooting has been revisited in several documentaries and crime series.

The 1981 Japanese-American documentary The Killing of America included footage from the incident. In 2006, a British documentary titled I Don’t Like Mondays examined Spencer’s case in detail.

True crime television has also covered the shooting. Investigation Discovery’s Deadly Women featured it in the season two premiere episode, “Thrill Killers,” which aired on October 9, 2008. The Lifetime Movies series Killer Kids also portrayed Spencer’s crimes in the episode “Deadly Compulsion,” first broadcast on September 3, 2014.

But no documentary, no song, and no reenactment could ever fully explain the horror of what happened that Monday morning in 1979.