They came in silence.

A dozen men, maybe forty. Some with handkerchiefs pulled over their faces, others barefaced, indifferent. They walked through the front doors of the jail in Okemah, Oklahoma, as if they belonged there.

The jailer claimed he had no choice. They pressed a gun to his head, bound his wrists, gagged his mouth, and took his keys.

They did not have to ask for directions. They knew exactly where they were going.

They wanted the woman and her son.

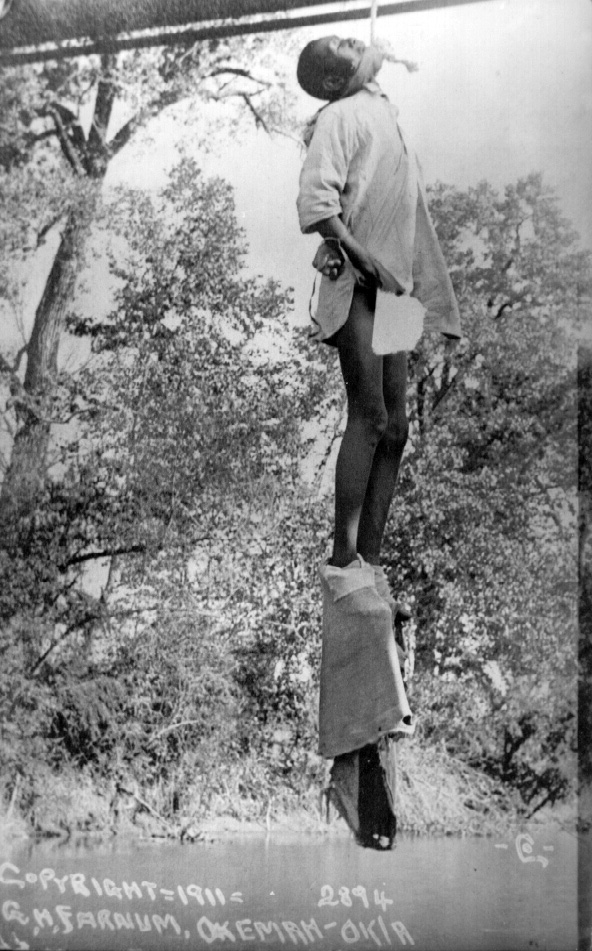

By morning, Laura and L.D. Nelson were dead. Their bodies swung from a bridge over the North Canadian River, left to twist in the wind, a spectacle for the town to see.

Why were Laura and L.D. Nelson in jail

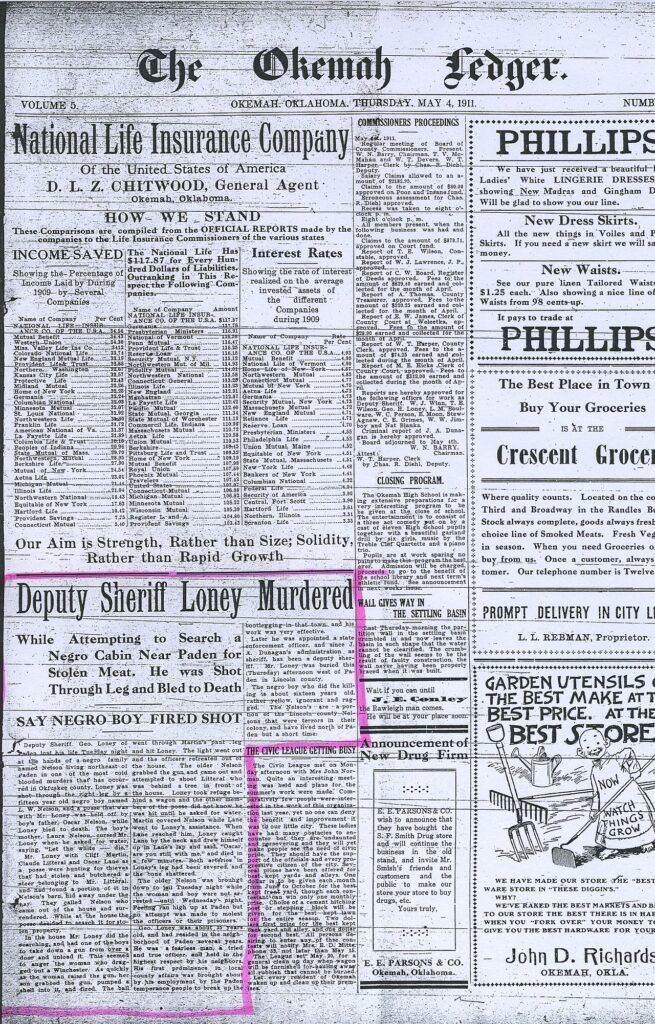

It started with a stolen cow.

That was the excuse, at least.

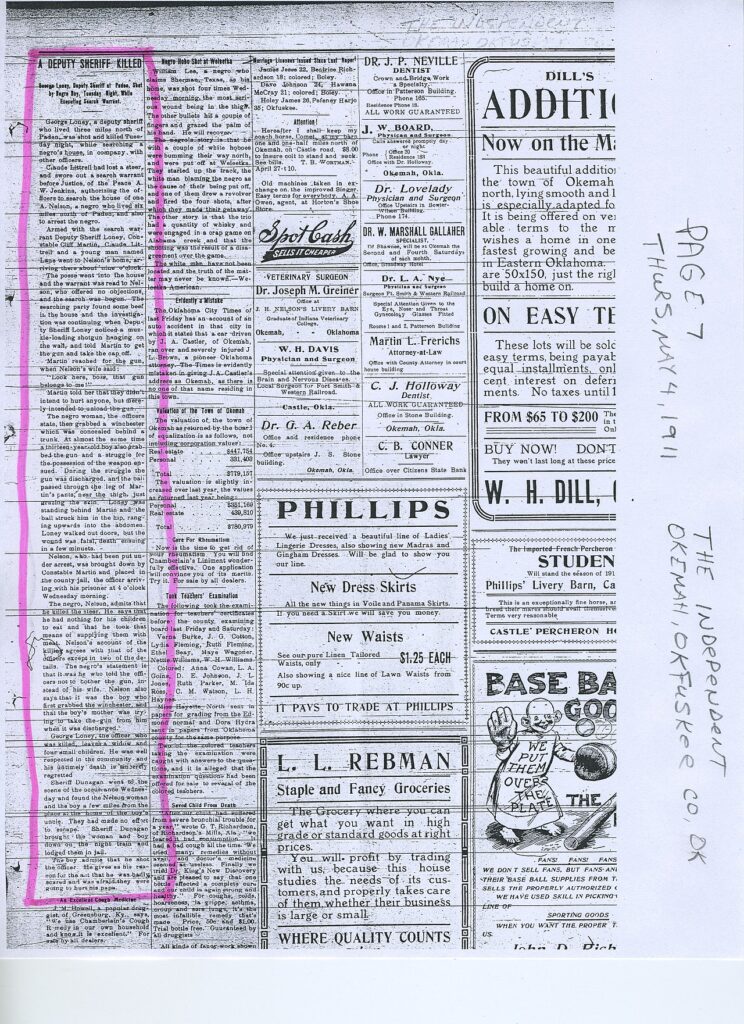

On May 2, 1911, Deputy Sheriff George Loney led a search party to the Nelson family farm, looking for stolen livestock. A cow had gone missing, and its remains were supposedly found in the barn.

Laura and her son, L.D., were inside when the deputies arrived.

The officers went for a gun hanging on the wall. What happened next depends on the source. Some say Laura grabbed the weapon first. Some say L.D. did. Some say it was an accident.

But a gun went off.

A bullet tore through the fabric of Deputy Loney’s pants, grazed another officer’s leg, and buried itself in Loney’s abdomen. He stumbled outside and collapsed. Within minutes, he was dead.

Laura and L.D. were arrested. They were charged with murder.

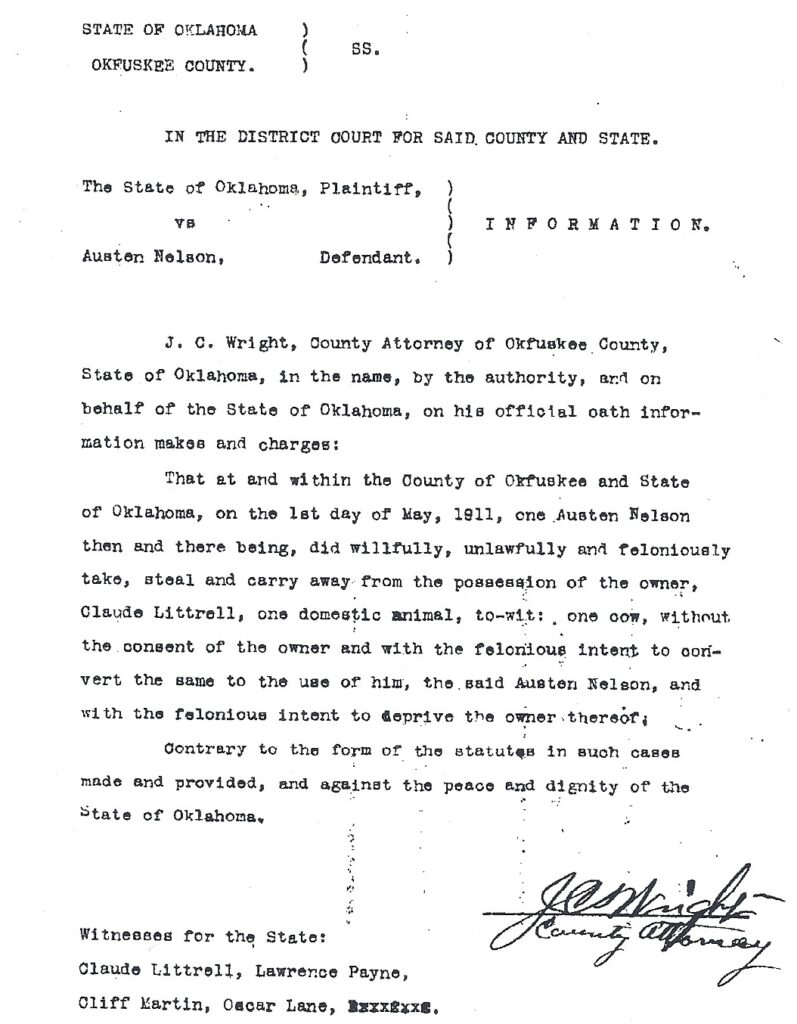

What happened to Austin Nelson

Austin Nelson, Laura’s husband and L.D.’s father, admitted to stealing the cow.

They gave him a trial. He pleaded guilty. The judge sentenced him to three years in the state penitentiary.

He was taken to McAlester, Oklahoma, sixty miles away.

Laura and L.D. remained in the county jail, waiting for their own trial.

The night the mob took them

They did not wait for justice.

On the night of May 24, 1911, the men entered the jail and walked straight to the cells where Laura and L.D. were being held.

L.D. went quietly. He was sixteen, maybe fifteen, some said even fourteen. A boy. The men gagged him, tied his hands, and led him out into the night.

Laura resisted. She fought.

The newspapers later reported that she begged them to kill her then and there, rather than take her from the cell.

They took her anyway.

She had a baby with her.

Some accounts say the child was found floating in the river. Others say a neighbor took her in, that she was raised in Okemah, lived a long life, grew up with the knowledge that her mother and brother had been taken in the night and hanged from a bridge.

But on that night, the mob left her behind.

Laura Nelson was raped

She was not only lynched.

The Associated Press reported what the town already knew but did not care to say: Laura Nelson was raped before she was killed.

This was not uncommon.

White mobs used lynching not just to kill, but to humiliate, to strip victims of dignity, to make it clear that their bodies were not their own.

They took what they wanted from Laura Nelson. And then they killed her.

How the lynching was carried out

The bridge was six miles west and one mile south of Okemah. The old Schoolton Road, some called it. Yarbrough’s crossing.

It was isolated enough to do the job.

They tied the nooses—thick, rough hemp ropes, knotted in a hangman’s coil.

They put one around L.D.’s neck, another around Laura’s.

There are no details of how long she fought. How long she begged.

No one wrote that down.

But when the morning light hit the river, their bodies were still hanging.

Laura’s arms were free, as if she had tried to claw at the rope, tried to fight the inevitable.

L.D.’s wrists were bound with a saddle string. His shirt had been torn. His body swayed twenty feet above the water, clothes barely clinging to him.

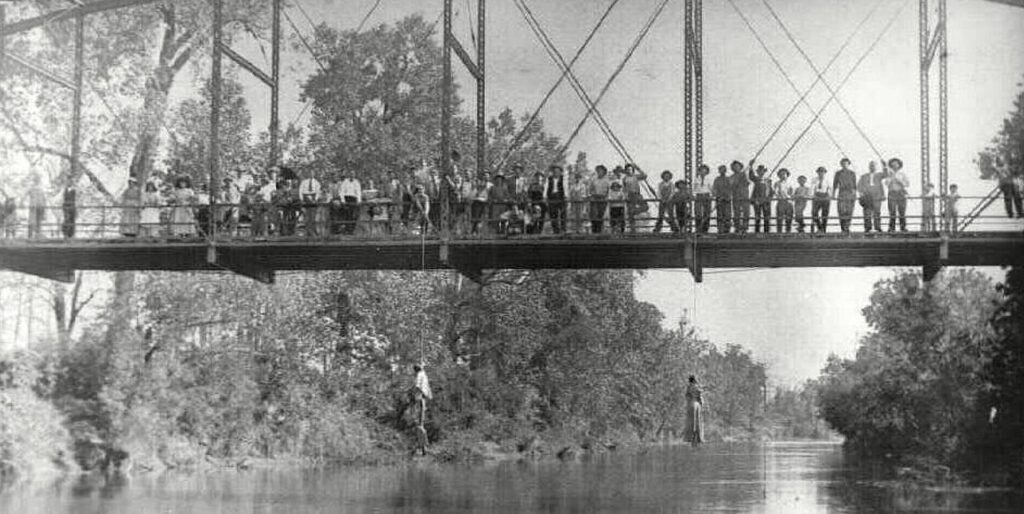

The crowd arrived soon after.

Why were photographs taken of the lynching

They did not look away.

They did not cover the bodies or call for quiet mourning.

They made it a spectacle.

Men, women, children—whole families gathered on the bridge to stare at what had been done.

A photographer arrived.

George Henry Farnum, Okemah’s only studio photographer, took the images. Close-ups of Laura’s body, L.D.’s broken frame, the bridge filled with spectators.

They printed the photographs on postcards.

They sent them to family, to friends, as if they were souvenirs from a fair.

In one of the images, toddlers stand at the front of the crowd, staring at the bodies below.

Did anyone try to stop the lynching

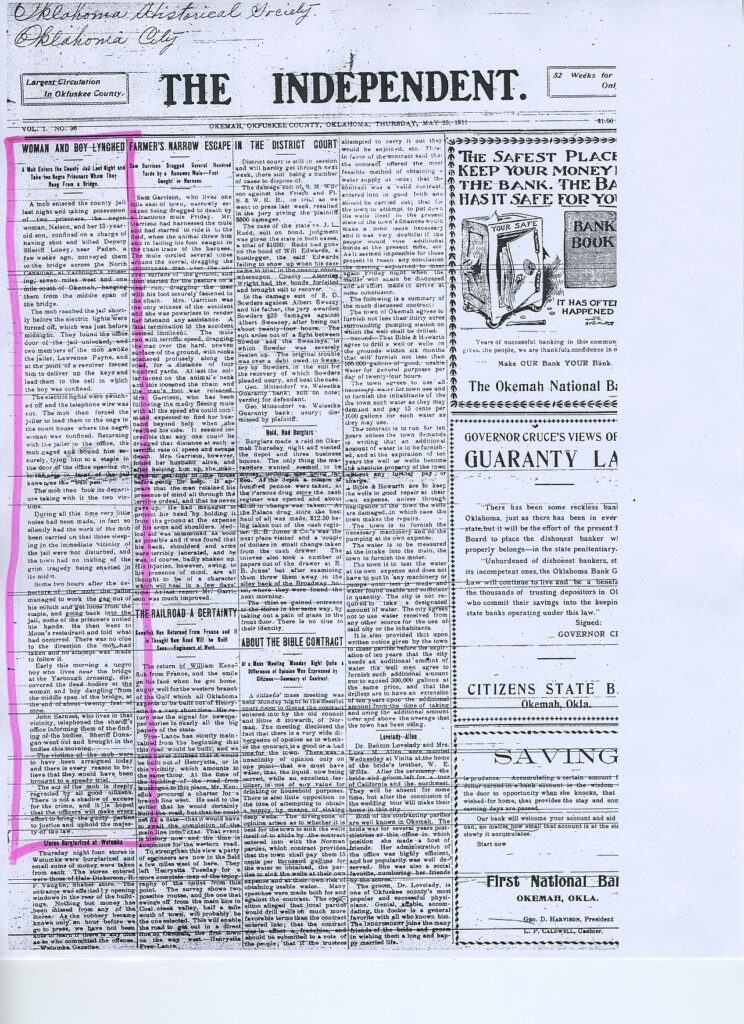

A grand jury was called.

The district judge asked them to investigate, to determine who had done this.

Not one man came forward.

Not one person admitted to being there.

The jailer had been gagged, he said. He saw nothing.

The sheriff had no suspects.

The governor of Oklahoma, Lee Cruce, called the lynching an “outrage,” but he would not call it murder.

He did not pursue the men responsible.

He blamed “race prejudice,” not the mob itself.

The jury returned no indictments. No arrests were made. No one was punished.

What happened to their bodies

Laura and L.D. Nelson were buried in Greenleaf Cemetery, their graves unmarked, their names erased.

The town moved on.

The photographs did not.

What was the legacy of their deaths

Woody Guthrie, one of Oklahoma’s most famous folk singers, grew up in Okemah. His father, Charley Guthrie, was rumored to have been part of the mob.

Woody never spoke of it directly.

But his songs carried a quiet rage, a deep understanding of injustice, of the way power could be abused, of how easily people could be discarded.

The photographs of Laura and L.D. Nelson are still here.

They are the only known surviving images of a Black woman lynched in America.

They are proof.

Proof of what was done. Proof of who was there.

The men in those photographs are gone.

Their names have been forgotten.

But history does not forget.

And neither should we.

And yet, over 100 years later, people still support racism. Men still believe themselves superior because of trivial particulars such as gender, race, religion, and so on.

You can head online and say, “Rape is bad,” and people, mostly men, seldom women, will argue against you.

We have learned nothing. We never will learn, because people let stories such as these die out. They don’t SHOW people, to their own face what people have done and what we continue to do.