A Murder That Shocked the World

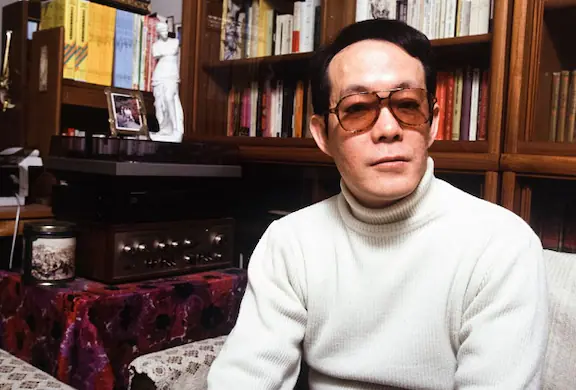

In 1981, Parisian authorities stumbled upon a discovery that horrified even seasoned investigators. A Japanese student named Issei Sagawa had committed a crime beyond comprehension.

He had murdered his Dutch classmate, Renée Hartevelt, then mutilated, cannibalized, and performed necrophilia on her remains. Police caught him trying to dispose of parts of her body.

This crime immediately drew worldwide attention. Journalists labeled Sagawa “the Kobe Cannibal,” referencing the city where he was born. The public demanded answers for such brutality.

As details emerged, people learned he was born prematurely on 26 April 1949, to a wealthy family in Kobe, Hyōgo Prefecture. His father headed Kurita Water Industries.

Sagawa’s fragile childhood health saw him battling enteritis, treated with injections of potassium and calcium in saline. Eventually, he recovered, but his life would turn sinister.

Despite the horror of his act, the greatest shock came when he faced no long-term prison sentence. Incredibly, he spent most of his life as a free man.

A Man With Dark Fantasies

Sagawa’s early years were marked by a fascination with literature. Because of his shy personality and constant health issues, books became his refuge and escape.

According to his own accounts, he first felt cannibalistic urges in the first grade. A glimpse of another student’s thigh sparked disturbing desires.

While still young, Sagawa engaged in bestiality with his dog and harbored fantasies about consuming women. He attended Wako University and later completed a master’s degree in English Literature.

His father, Akira Sagawa, was wealthy, and Sagawa’s grandfather had been an editor for The Asahi Shimbun. Privilege, however, did not shield him from twisted obsessions.

At age 24, he broke into a German woman’s apartment, intending to slice off part of her flesh for consumption. She awakened and overpowered him, foiling the attempt.

Charged with attempted rape, he never revealed his actual cannibalistic motive. His father’s settlement payments ensured the charges were dropped, allowing him to avoid any real legal repercussion.

The Target: Renée Hartevelt

Years later, Sagawa moved to Paris in 1977 to study for a PhD at the Sorbonne. His appetites grew more intense, yet he struggled to act on them.

He spoke openly of inviting sex workers home, planning to shoot them, but claimed his fingers froze on the trigger. This pattern continued until he met Hartevelt.

Renée Hartevelt was a Dutch student pursuing her own academic goals in Paris. She stood about 178 cm tall, strikingly different from Sagawa’s short stature of 145 cm.

Sagawa fixated on her physical attributes, seeing her as healthy, beautiful, and embodying traits he felt he lacked. He believed consuming her would grant him those qualities.

On 11 June 1981, he convinced Hartevelt to come to his apartment at 10 Rue Erlanger under the guise of translating poetry for a class assignment.

While Hartevelt read at his desk, Sagawa stood behind her with a rifle, preparing to fulfill the dark fantasy he had carried for years.

The Murder in Paris

Sagawa shot Hartevelt in the neck, killing her instantly. He claimed to have fainted momentarily, overwhelmed by the act he had just committed.

Upon regaining his senses, he felt compelled to carry out his planned ritual of cannibalism. For him, that moment was the culmination of lifelong impulses.

The murder itself was horrifying, but more unsettling was what came next. Sagawa did not merely dispose of the body; he had other, more depraved intentions.

In his mind, this was an act of both consumption and possession. He believed eating her flesh would let him absorb her beauty and vitality.

He had chosen Hartevelt meticulously, admiring her intelligence and appearance. In his twisted worldview, devouring her meant claiming every trait he envied or desired.

Investigators later learned he specifically targeted her for these reasons, which made this crime far more calculated than a spontaneous act of violence.

The Act of Cannibalism

After killing Hartevelt, Sagawa realized his teeth could not tear through her flesh. He left the apartment to buy a butcher’s knife for dismemberment.

He raped her corpse, committed acts of necrophilia, and then began dissecting her body. This entire ordeal lasted for several days.

Parts of her flesh were eaten raw, while other pieces he cooked. He photographed each stage, creating a macabre record of his actions.

Sagawa later admitted consuming Hartevelt’s thighs, buttocks, face, and certain internal organs. He described the taste as “melting” and claimed it brought him indescribable pleasure.

Disturbingly, he even tried to eat portions that repulsed him, such as her clitoris during her menstrual cycle, but found the smell of menstrual blood unbearable.

By the end, decomposition forced him to consider disposing of what remained. This decision led directly to his eventual capture by the authorities.

Caught Red-Handed

With the body decomposing, Sagawa stuffed the remaining parts into two suitcases. He intended to dump them in the Bois de Boulogne, a public park in Paris.

Despite careful planning, he acted nervously. Bystanders observed him struggling with heavy luggage near the lake. Their suspicions led them to call the police.

When officers opened the suitcases, they discovered Hartevelt’s dismembered remains. Sagawa offered no resistance or denial. He confessed everything without hesitation.

His calm demeanor unnerved investigators. He admitted to killing Hartevelt for the sole purpose of cannibalizing her. His explanation revealed a disturbing lack of remorse.

This immediate confession underscored how meticulously he had planned the crime. The shock value escalated as details of his cannibalistic methods spread.

Overnight, Sagawa became a media sensation. Yet the most surprising chapter of his story was still to unfold in the French legal system.

A Legal Loophole Sets Him Free

French prosecutors initially prepared to put Sagawa on trial, but psychiatric evaluations deemed him legally insane and unfit for normal judicial proceedings.

Instead of a criminal prison sentence, he was ordered to remain indefinitely in a mental institution. This was meant to protect society from his impulses.

Several years later, French authorities transferred him to Japan. The assumption was that Japanese officials would keep him institutionalized, preventing any return to public life.

However, when he arrived at Matsuzawa Hospital in Tokyo, Japanese psychologists unanimously declared him sane. Their assessments focused on his sexual perversion as the core issue.

Because the French court records were sealed, Japanese authorities lacked the evidence needed to bring fresh charges. Legally, there was no case to pursue.

Just five years after the murder, Sagawa checked himself out of the hospital in 1986 and walked free, sparking global outrage at the system’s failure.

From Killer to Celebrity

Suddenly liberated, Sagawa capitalized on his notoriety. He published graphic accounts of the murder, including a work titled In the Fog, which gained attention in Japan.

Media outlets invited him as a commentator, intrigued by his shocking story. He appeared on talk shows, openly describing the taste of human flesh.

His story even crossed into exploitation cinema. In 1992, he featured in Hisayasu Sato’s film Uwakizuma: Chijokuzeme, playing a sado-sexual voyeur in a storyline reflecting his past.

He wrote books about the 1997 Kobe child murders and even served as a restaurant reviewer for Japanese magazines. Public fascination kept him in demand.

Many found his rise to minor celebrity deeply disturbing. Critics saw it as profiting from an atrocity, turning a brutal crime into a lucrative spectacle.

The debate intensified over whether media outlets should grant a platform to a confessed murderer and cannibal, essentially rewarding him for his gruesome past.

A Life of Infamy and Isolation

Over time, society’s shock turned to exhaustion. Publishers became wary of associating with Sagawa, cutting him off from easy income. Employment opportunities vanished.

In 2005, both his parents died. He was barred from attending their funeral. He settled their debts but moved into public housing, eventually depending on welfare.

In a 2011 Vice interview, Sagawa expressed that living with his own name and history was itself a punishment. Yet remorse remained unclear in his statements.

In 2013, he suffered a cerebral infarction that led to permanent damage to his nervous system. He required assistance from his brother or caregivers.

Once an active commentator, he found himself physically and socially isolated. The man who once sparked furious headlines drifted into a quieter, troubled existence.

Sagawa insisted he regretted his obsessions, though his public demeanor had long suggested otherwise. His health decline offered a stark contrast to his earlier celebrity phase.

Why This Case Still Haunts People

On 24 November 2022, at the age of 73, Sagawa died in a Tokyo hospital from pneumonia. His passing closed a final chapter on a baffling life.

Yet the legacy of his crime endures. His freedom after the heinous act shocked observers, raising questions about legal loopholes and international justice.

Sagawa’s case also spotlighted media ethics. Some outlets embraced his notoriety for ratings or book sales, effectively feeding the public’s dark fascination.

Pop culture responded with references. The Rolling Stones’ “Too Much Blood” and The Stranglers’ “La Folie” drew inspiration from his story, highlighting its grim cultural impact.

Documentaries like Interview with a Cannibal and Caniba explored his psyche, grappling with the moral weight of giving him any further public attention.

Even in death, Sagawa represents a disturbing paradox: a murderer and cannibal who walked free, leveraged infamy, and left behind a trail of unsettling questions.

The injustice felt by Hartevelt’s family remains a central issue. Her memory is overshadowed by the man who killed her, turning personal tragedy into public spectacle.

Ultimately, the Kobe Cannibal’s story endures as a chilling reminder that sometimes, the most shocking element isn’t just the crime itself, but the aftermath that follows.