On a Sunday evening in late May 2003, the control tower in Luanda watched something that should never happen at a modern airport. A Boeing 727 rolled from its stand without a word to anyone, swung through its turns like a nervous driver, lined up on the runway with lights dark and transponder silent, then thundered into the Angolan twilight. No clearance. No flight plan. No goodbye.

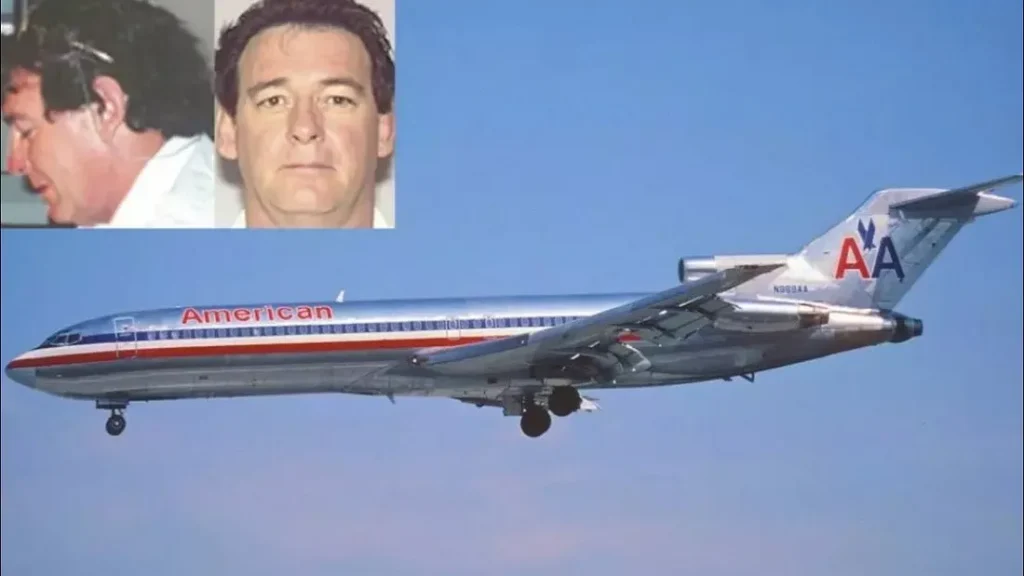

The airplane wore the tail number N844AA and a weathered coat of bare metal with a red, white, and blue cheatline. Two men were believed to be aboard. Neither was rated to fly a 727, a jet that usually needs three qualified crew. Within minutes the aircraft vanished over the Atlantic and entered aviation folklore. No confirmed radar track. No emergency call. No debris. Nothing.

This is the story of how a retired American airliner wound up in one of the messiest business environments on earth, why so many people around it had motives that do not line up neatly, and how four competing explanations can each feel convincing for a few pages before dissolving under the weight of missing facts.

It is also a reminder that some mysteries refuse to leak even a drop.

The Last Taxi

Sunset in Luanda on May 25, 2003 arrived just after five in the evening. Sometime before that, ground staff at Quatro de Fevereiro International saw movement at a remote stand. N844AA, parked there for more than a year, started to taxi. One airport employee later swore there was only one person inside. Others insisted they saw two men board. The jet turned in a way that looked wrong, almost anxious, and radio silence held. Controllers tried to call. No reply.

Then power came up. With landing lights off and transponder dark, the 727 accelerated and lifted southwest over the ocean. The tower kept calling. The jet kept going.

A Boeing 727 is not a Cessna you can wing off the ramp. Even starting its three engines takes knowledge and a sequence. Whoever rolled that airplane knew enough to get it moving and airborne, which does not answer the question that matters. Did they know enough to keep it there.

A Jet With a New Job

N844AA began life in 1975 as an American Airlines workhorse. After 25 years, the airline let it go. By 2002 the airplane belonged to Aerospace Sales & Leasing in Florida. It had been ferried to Angola to serve a client in a strange niche. The plan was to haul diesel to remote diamond fields that roads could not reliably reach.

The cabin no longer looked like an airliner. Most seats had been stripped out. In their place sat ten cylindrical tanks, five hundred gallons each, strapped and plumbed. A few passenger chairs survived for ferry legs. Unpaid airport fees built up in the background and eventually passed fifty thousand dollars. Some people in Luanda believed the registration had been swapped out to 5N-RIR on paper. Others called that a fig leaf for a plane that could not legally go anywhere.

From the outside, the jet looked tired but distinctive. Bare aluminum. Faded stripes. A profitable machine turned into a rough tool.

Angola’s Pressure Cooker

To understand why a 727 might simply leave, you need the setting. Angola in the early 2000s was emerging from decades of civil war. The people around N844AA were hustling through a world where police carried rifles, deals broke overnight, and competitors did not just undercut on price. They threatened. They pushed. They sometimes crashed.

A crew member from one of the early ventures later said he was scared to death and that the team hired an armed guard to watch their door. A separate 727 in a rival operation crashed on approach and killed residents on the ground. The story gets uglier. Instead of joining the rescue, men from the Luanda scene stripped parts from the wreck to keep their own project alive.

In that kind of pressure, moral lines fade into the heat haze. If a group talked about stealing its own airplane to escape the country, it did not sound like fiction.

The People Around the Plane

Ben Charles Padilla

Ben Padilla was a rare hybrid. He held flight engineer credentials, knew his way around wrenches, and had a private pilot license. He had worked with the aircraft’s owner before and had been sent to Angola to make N844AA airworthy for a return to the United States. By most accounts he could start a 727, taxi it, and manage its systems. Flying it through a takeoff and climb would demand more, but not impossibly more, if you accept risk.

Ask his family and you get a man who would not do a crooked thing. Ask a former employer who clashed with him and you get a man prone to tall stories and bad decisions. In a mystery that already lacks metal, the portrait of Padilla becomes another missing piece. He could be the resourceful engineer who got trapped in a bad situation. He could be the impulsive fixer who chose the wildest option in the worst place.

John Mikel Mutantu

Padilla hired a Congolese-French mechanic named John Mikel Mutantu soon before the disappearance. Mutantu was not a pilot. He may have been aboard. If he was, he would have been the one person who could help run checklists, read gauges, and manage systems while Padilla tried to fly. If he was not there, then the problem becomes more severe. A single unqualified pilot taking a 727 solo into dusk is a recipe for error.

The records do not agree. That split sits at the center of the case like a loose rivet you cannot find.

The Owner and the Dealmakers

Aerospace Sales & Leasing was led by a Florida businessman named Maury Joseph. In the 1990s he faced civil charges from the Securities and Exchange Commission for misleading investors. In Angola he struggled to turn the 727 venture into an actual revenue stream. He first leased the airplane to a South African operator named Keith Irwin. The partnership broke down. The airplane sat. The bills grew.

Joseph portrays himself as a victim. He says he called the U.S. Embassy and the FBI as soon as the plane went missing and even volunteered for a polygraph. He also says Irwin owed money, that the market was cut-throat, and that he was trying to unwind a mess while others hid their agendas.

Irwin paints a world of threats and stray gun barrels. He says his team was so frightened they considered stealing the airplane to get out of Angola alive. Another figure on the edge of the story, a buyer interested in the 727’s engines, says he was with Joseph when the news hit and that Joseph looked stunned.

The result is a credibility vortex. Everyone has a version. Everyone has a reason to shade it. The more you listen, the less you trust.

What Happened After Wheels Up

Once the 727 lifted into the dusk, answers should have gotten easier. They did not. The airplane had about 53,000 liters of fuel, roughly 14,000 U.S. gallons, which gave it a range in the neighborhood of 2,400 kilometers. That could reach deep into Central Africa and touch remote strips that do not show up on glossy maps.

There were reports of a sighting in Conakry, Guinea, in July. The U.S. State Department dismissed it as false. No radar track ever became public. No oil sheen washed ashore. No fragment of polished aluminum showed up in mangroves. A Boeing 727 is not small. The absence of physical evidence is the single fact that keeps this story strange long after it should have settled into one bin or another.

Four Ways the Story Could End

When investigators hit a wall, they build doors. In this case there are four.

1) Padilla Stole the Plane

This is the most popular explanation. It starts with a motive. The airplane was stuck. Money was bleeding. Padilla knew how to light the engines. With help from Mutantu he could have taxied, forced the takeoff, and pointed toward a remote strip where a buyer would pay for a flying machine or at least for its engines and controls.

The pieces fit until you ask where the airplane went. Stripping a 727 requires time, a safe location, and trucks or a ship. Someone talks. Someone bragged in a bar. Someone posted a photo. Two decades later, nothing has surfaced that holds up. It is possible to move large objects quietly in Central Africa. It is not easy to make one disappear forever.

2) A Forced Hijacking

Padilla’s family has long believed he was a victim, not a thief. In their view, a third party used him or seized the airplane with him inside. In Angola that does not sound far-fetched. The atmosphere around the airplane was tense and often ugly. If you imagine a rival or creditor who wanted a jet more than they wanted an argument, it becomes plausible that someone with a weapon got aboard before Padilla did.

The trouble begins when you look for marks of force. No calls. No demands. No trail of ransom, revenge, or politics. The erratic taxi could be a struggle. It could also be a mechanic trying to be a pilot. Without a message or a claim, hijacking floats as an idea, not a conclusion.

3) An Insurance Play

Given Joseph’s old SEC case, some investigators wondered whether the disappearance was a very expensive version of cutting losses. If the venture was upside down and the aircraft a stranded liability, a claim might look tempting. That theory weakens when you look at the reaction. Joseph reported the theft immediately and pledged to take a polygraph. You can fake surprise. It is harder to invite the FBI into your living room if you planned it.

The insurance angle also requires a chain of cooperation that looks unlikely. Would Padilla risk his life and freedom to solve the owner’s balance sheet. Would Mutantu. In a world full of messy incentives this one still feels overly tidy.

4) A Crash Soon After Takeoff

The simplest explanation is often the best. The engines are loud. The cockpit feels familiar enough to a flight engineer. The checklist is a blur. The jet rotates a little fast. A few minutes later the airplane meets the ocean. A 727 is designed for a three person team. One man at the yoke and another juggling systems in poor light can make mistakes that leave no time for a call.

This account runs headfirst into the stubborn absence of wreckage. Coastal crashes usually leave something. Seat cushions. Life vests. Papers. Fuel. The Atlantic can hide secrets, yet the scale here is hard to ignore. An entire airliner does not vanish cleanly a few miles from a capital city.

The Post-9/11 Panic

The date matters. The airplane disappeared less than two years after the September 11 attacks. A stolen airliner was not just a theft. It was a possible weapon. The United States treated it that way. The FBI and other agencies launched a sweeping search and shared notes with partner services. There was even talk inside U.S. Central Command about moving fighters to Djibouti as a hedge against a bad surprise.

Weeks passed without a hint of terrorism. No threats appeared. No group claimed credit. The intensity ebbed. The FBI formally closed its investigation in 2005. The public record stops there. It is reasonable to assume that intelligence agencies built a view that pushed them away from a terror scenario. If they did, it never reached daylight.

Why No Debris

The absence of evidence has become its own character in this story, so it deserves a closer look. There are three ways you get a debris-free case. The airplane lands somewhere remote and stays intact. The airplane crashes far enough offshore that the currents spread remains across a broad area and the pieces sink. Or the airplane never existed in the way the story remembers it.

The last option can be dismissed. Too many witnesses saw the jet. Too many bills document its presence. That leaves the first two. A successful landing on a quiet strip is possible when your pilots are experienced, your runway is long, and your support is waiting. In this case, none of those three were guaranteed. A crash offshore is physically simple and statistically plausible. It just struggles with the fact that airplanes shed things that float.

You can decide which discomfort you prefer. A ghost landing that never left a footprint. Or a clean crash that never left a scar.

The Human Center of an Unhuman Mystery

When an airplane disappears, it is tempting to talk only about machines and maps. Two men were inside this story. Padilla had a sister and a brother who still insist he would not have crossed a line. Mutantu’s life is largely a blank in the public file, which is its own quiet tragedy. Both men walked up a set of stairs and into a cabin stripped for fuel drums. Both men were last seen through glass, not a lens, by tired workers at a field where armed guards watched doors.

We remember the airplane because airplanes are big. We should remember the people because they were not.

What We Really Know

Strip the rumors away and a handful of facts remain.

- N844AA, a 1975 Boeing 727 once flown by American Airlines, sat in Luanda for more than a year and had been modified to carry diesel in ten tanks.

- The airplane had built up significant fees and had been the focus of failed business deals in a threatening environment.

- On May 25, 2003, the airplane taxied without clearance, took off at dusk with lights and transponder off, and turned toward the Atlantic.

- Two names are tied to the departure. Flight engineer and mechanic Ben Charles Padilla. Hired mechanic John Mikel Mutantu. Neither was a qualified 727 pilot.

- The jet had enough fuel to fly about 2,400 kilometers. No verified sighting followed. A report from Guinea was dismissed. No debris has been found.

- The FBI closed its public case in 2005. No government has offered a final explanation.

That list is shorter than the list of theories. It is also the only ground that does not move.

The Case Study Nobody Wants

People in aviation like closed loops. A malfunction points to a component, the component points to a maintenance error, the error points to a process failure, and the process gets fixed. This is not that kind of story. Here the malfunctions belong to trust, money, fear, and pride. Every witness has a reason to tilt the table. Every partner has a grievance. Every timeline has a smudge.

Look hard enough and you can make an argument for theft that feels sharp until it dulls under the metal-free silence of the years. Look from another angle and you can make an accidental crash sound statistical until you remember that the sea is generous with its secrets only some of the time.

Angola supplied the stage. The airplane supplied the size. The people supplied the contradictions.

The Ending That Does Not End

Two decades on, the disappearance of N844AA still reads like the opening chapter in a book that never shipped. The takeoff is vivid. The middle is frantic. The last page is blank. Serious investigators who lived inside the case for months will tell you the same thing. You can balance motives. You can map ranges. You can model climb performance with two people doing three jobs. In the end you will hit a wall built from the lack of physical evidence.

If you force a verdict, theft for financial gain with Padilla at the controls is the most practical match for motive and means. If you force another, an accidental crash in the first minutes explains the erratic ground roll and the silence in the air. If you demand proof, neither has it.

That is the point. Some disappearances keep a piece of themselves forever. In a world where satellites watch oceans and airports log every squawk, one airliner from the 1970s rolled into the Angolan dusk and took its truth with it. You can stare at the ramp where it started, trace a finger down a map of West Africa, and rehearse the four exits over and over. The doors never open.

Some mysteries entertain because they promise a solution on the next page. This one endures because the next page was never written.