Dorothy Harriet Camille Arnold had everything money could buy. Born in 1885 into one of Manhattan’s most prominent families, she lived in a stately home at 108 East 79th Street, attended finishing schools, and was expected to marry well. Her father, Francis Rose Arnold, was a successful perfume importer with ties to the elite. Her social circle included debutantes, Ivy Leaguers, and the children of industrialists.

But beneath the surface of privilege, Dorothy was quietly waging a war of her own. She wanted something that didn’t come with family connections or inherited wealth—she wanted to be a writer.

After graduating from the Veltin School for Girls, she pursued literature, even submitting short stories to magazines like McClure’s. None were accepted. Her family, especially her father, found this aspiration laughable. At dinner parties, he reportedly mocked her ambitions. And so, Dorothy began receiving her rejection letters at a rented post office box—a silent rebellion against the household that would rather see her married than published.

In 1910, at age 25, she was still unmarried and living at home. In the eyes of her world, she was already edging into spinster territory. But to Dorothy, life was still unwritten. She was determined to live beyond the scripts society handed her. That may be why, when she left home on the morning of December 12, 1910, she didn’t say exactly where she was going—or what she was really searching for.

The Last Day We Saw Her

It was a crisp Monday in New York City. At around 11:00 a.m., Dorothy left the house wearing a blue tailored coat with a broad black velvet collar, matching hat, and high-heeled boots. She told her mother she was going shopping for a dress for her younger sister’s debutante ball. Her mother offered to join, but Dorothy declined, saying, “If I find anything I like, I’ll telephone you.”

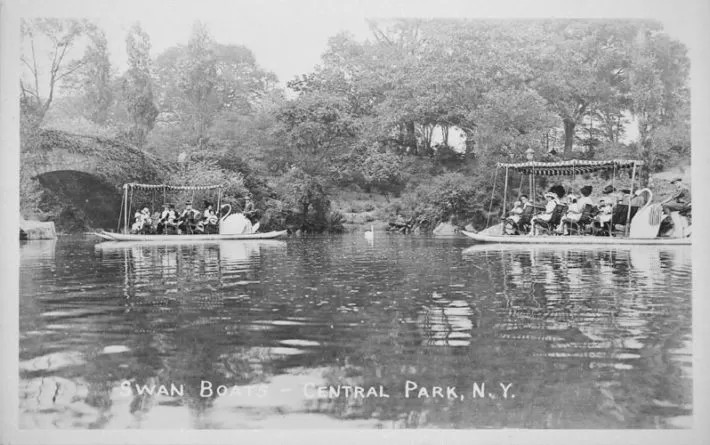

Instead, she browsed around Fifth Avenue, stopping at Park & Tilford to buy a box of chocolates and then at Brentano’s bookstore, where she purchased Engaged Girl Sketches by Emily Calvin Blake. Both items were charged to her father’s account. The clerks who saw her said she seemed cheerful, composed, unhurried. Around 2:00 p.m., she ran into a friend named Gladys King on 27th Street and said she was planning to walk home through Central Park.

That was the last time anyone could confirm seeing Dorothy Arnold.

She vanished in broad daylight, on a busy Manhattan street, with no scream, no signs of struggle, no trace. She was carrying around $25—enough for cab fare or lunch, but hardly enough to stage a disappearance. There were no known enemies. No former lovers to suspect. No obvious threats.

That silence—that lack of chaos—was what made the case so unnerving.

When Silence Becomes Scandal

Dorothy didn’t come home for dinner. Her family noticed, but they didn’t panic—at least not outwardly. As the hours passed, they made a stunning decision: they wouldn’t report her missing.

Francis Arnold believed it would attract too much gossip and embarrass the family name. Instead of calling police, he contacted a lawyer, John S. Keith, and asked him to quietly investigate. Keith searched Dorothy’s bedroom and found nothing out of place. Her clothes, jewelry, and personal belongings were all untouched. But one thing caught his eye: foreign-stamped letters and brochures for transatlantic steamship lines.

Privately, the family wondered: had she run away? Was she planning something they didn’t know about? But publicly, they lied.

That evening, when Dorothy’s friend Gladys called to check in, her mother answered the phone and claimed Dorothy was already home and resting in bed. The following day, the charade continued. The family avoided public attention, hoping, perhaps, that Dorothy would quietly reappear—or that they could explain away her absence with minimal scrutiny.

But days turned into weeks. By the time they contacted the police, the trail had gone cold.

What the Room Left Behind

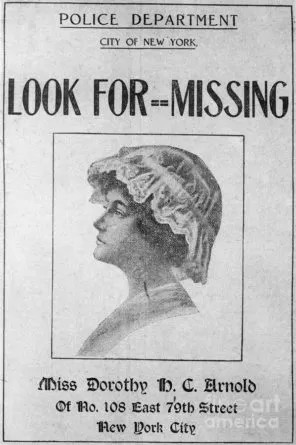

Despite their late start, the investigation quickly drew attention. The missing heiress became front-page news. Posters with Dorothy’s image were printed. Sightings flooded in from cities across the country. But nothing solid emerged.

What stood out most were the details not found.

There was no evidence of packed bags. No personal notes. No sign she had taken any prized possessions. Dorothy was gone, but she hadn’t prepared to go anywhere.

The items in her room raised more questions than answers. The foreign postmarks hinted at correspondence outside the country, but no recipients were ever identified. The cruise pamphlets suggested she may have been fantasizing about escape—or making plans. But again, her father was quick to dismiss the idea. “She had no money,” he insisted. “She could not have gone anywhere without asking me.”

But that claim said more about Francis Arnold’s assumptions than about his daughter’s reality. Dorothy wasn’t completely dependent—she had a small allowance, enough to rent a mailbox and buy books. She had secrets. She had ambition. She had frustration.

She had reasons to want out.

Lawyer John S. Keith would later suggest that perhaps Dorothy had indeed planned to leave—possibly to elope, or to chase freedom far from Fifth Avenue. But then came the counterpoint: if she ran away, why didn’t she take anything with her?

By the time 1911 began, the story was no longer just about a missing woman. It was about the invisible pressures of womanhood, the cost of failure, and the silence of privilege.

A Citywide Hunt with No End

Once the Arnold family finally involved the police and the press, the story of the missing heiress exploded across national headlines. Society papers ran her photo beside gossip and speculation. The New York Times chronicled updates obsessively, while The Evening Star published witness accounts and cryptic tips. The family offered a reward, private detectives retraced her last known steps, and sightings poured in from New Jersey, Philadelphia, and even California.

None panned out.

There was no ransom demand, no body, no proof of a crime. And that’s what made it worse. If Dorothy had been kidnapped, there was no trail. If she had left of her own accord, she had done so in complete silence. In one of the most crowded cities on Earth, it was as if she had vanished into vapor.

Francis Arnold remained both emotionally devastated and socially defensive. He appeared before reporters weeks after the disappearance to say:

“My daughter is not in Europe. If she were there, she would have communicated with us before this. I believe she has been killed.”

Yet even that theory lacked foundation. There were no suspects, no witnesses, and no evidence of foul play. But it was easier, perhaps, to believe in a random act of violence than to consider the possibility that Dorothy had left because home had become unbearable.

The Postcard, the Abortion Theory, and the Missing Years

Then, a new wrinkle appeared.

Several weeks after the disappearance, Francis received a postcard at his office. It was brief. It read, “I am safe” and was signed simply, “Dorothy.” The handwriting, he admitted, was strikingly similar to hers. But he refused to believe it was genuine.

He called it a hoax. A cruel joke. A distraction.

The police weren’t so quick to dismiss it. They considered the card, along with other circumstantial clues: the steamship flyers, the foreign mail, the rumor that Dorothy had visited a steamship office on the day she vanished, inquiring about cruises to the West Indies. Could she have boarded a ship under a false name? Could she have left for good?

There was another, darker theory: abortion.

In 1916, six years after Dorothy disappeared, police raided a home in Bellevue, Pennsylvania. In the basement, they uncovered an illegal abortion clinic run by Dr. C.C. Meredith. Records showed that women had died there—quietly, without burial, without notice. Some, investigators believed, were buried on the property. Among the whispered names of possible victims was Dorothy Arnold.

The theory went like this: Dorothy had become pregnant, sought an abortion, and died during the procedure. The clinic disposed of her body, and her disappearance became just another unsolved mystery.

Francis Arnold dismissed the idea outright, calling it “ridiculous and absolutely untrue.” But he would have, wouldn’t he? For a man obsessed with reputation, the suggestion that his unmarried daughter had been pregnant—and died in secret—was unacceptable. Even in death, Dorothy had to be virtuous. Even in mystery, she had to remain respectable.

But her own words suggested otherwise.

The Father’s Last Words

Before her disappearance, Dorothy had written a letter to a close friend that read:

“Failure stares me in the face. All I can see ahead is a long road with no turning. Mother will always think an accident has happened.”

This was the most direct insight into Dorothy’s state of mind. Repeated rejections of her writing, the dismissiveness of her family, and the slow erosion of her independence had taken a toll. She had gone from being a celebrated debutante to a deeply frustrated young woman with no way out.

For John S. Keith, the family lawyer who had first searched Dorothy’s room, this was the most plausible answer. After both of her parents had died, he spoke publicly for the first time:

“I believe she took her own life. The circumstances point that way.”

But again, there was a problem: no body.

If Dorothy had died by suicide in Central Park, as many theorized, wouldn’t she have been found? The lake had been frozen that day, and when the ice melted, police searched the water thoroughly. Nothing. No clothing, no remains, no trace.

If she had planned suicide in another location, she would’ve had to disappear without any of her belongings, with no farewell note, and no chance of being discovered. That too seemed unlikely.

So Francis Arnold clung to the one belief he never let go of:

“I believe my daughter is dead. I believe she died the day she disappeared or almost immediately afterwards. The one theory to which I have always leaned is that she was kidnapped and made away with in a short time.”

That belief gave him closure. But not answers.

Why This Case Still Haunts Us

Dorothy Arnold’s story was never solved. She became a footnote in early 20th-century crime lore—another socialite swallowed by mystery. But what keeps her case alive isn’t just the lack of resolution. It’s what the case reveals about women like her, and the world they lived in.

Dorothy wasn’t a tragic romantic. She wasn’t a scandalous rebel. She was an ambitious woman, born into the wrong decade. In 1910, her options were limited: marry well, play nice, stay quiet. She tried to break out, and when she failed, her own family treated her disappointment as a joke.

So when she vanished, the world around her couldn’t agree on what mattered more: finding her—or protecting the family’s name.

If she died in an alley or an operating table, the shame was too great to admit. If she left for a better life, her independence was too offensive to forgive. And if she was killed, her family’s silence may have buried the truth.

Dorothy didn’t just disappear. She was erased. By the assumptions of the time. By the arrogance of wealth. By a world that couldn’t imagine a woman wanting something more—and punished her for it when she did.

And that’s what makes this case endure.

Not just because she was never found, but because no one ever really looked in the right places.