In the winter of 1994, Fred Boyce was listening to his car radio when he heard something he could not believe. A government committee had revealed that children at a Massachusetts institution were once fed radioactive cereal. It had happened fifty years earlier.

Boyce froze. The institution they mentioned was the Fernald State School. He had lived there as a child. “That’s me,” he said out loud, stunned by what he was hearing.

Back in the 1940s, Boyce had joined something called the Science Club. He was one of about 90 boys who signed up. They were promised rewards like extra food and tickets to baseball games.

But this wasn’t a regular school club. It was a cover. Behind it was a quiet partnership between researchers at MIT and one of America’s biggest cereal brands.

A Club With a Different Purpose

In the post-war years, breakfast cereal was booming. Quaker Oats and Cream of Wheat were competing for dominance. But there was a problem. Scientists had begun to question how nutritious these cereals really were.

Some grains, they found, contained an acid called phytate. It made it harder for the body to absorb key minerals like iron and calcium. Cereal companies needed proof their products still delivered value.

Quaker Oats decided to take the issue into their own hands. They partnered with MIT to run experiments that would help their brand. It was a business decision, dressed up as a scientific one.

MIT secured funding from Quaker and from federal agencies. This included support from the Atomic Energy Commission. Then they created a plan to test how the body absorbed nutrients—by using radioactive tracers.

These tracers helped researchers see where nutrients went inside the body. But they also came with risks. And the people consuming them had no idea what they were signing up for.

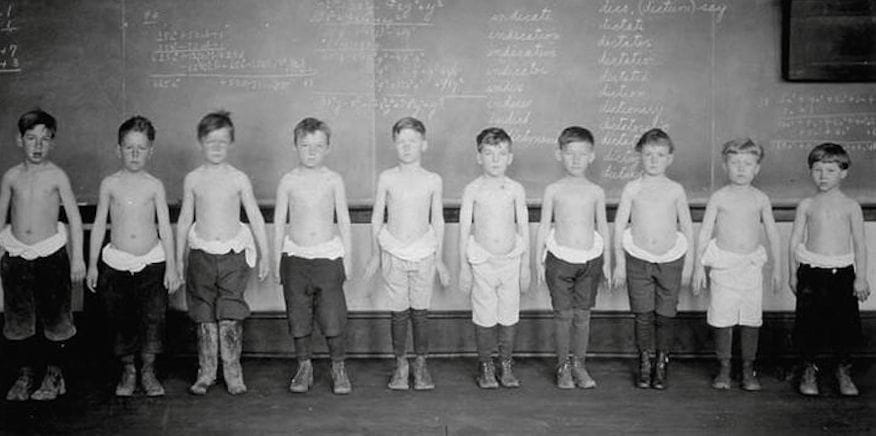

The Perfect Subjects

The team at MIT needed test subjects. They wanted children with no outside contact, no legal guardians asking questions, and no ability to say no.

They chose the Fernald State School. It was a state-run home for children labeled “feeble-minded.” Many were abandoned by their families. Some didn’t have any known disabilities at all.

Fernald’s reputation was already grim. In the early 1900s, its director, Walter Fernald, was a major voice in the eugenics movement. He believed certain people were less valuable to society.

Some kids at Fernald had been placed there simply because they misbehaved. Others were from poor homes or orphanages. They were told they didn’t belong in normal society.

To the researchers, these children were ideal. They wouldn’t ask questions. They were easy to monitor. They could be persuaded with small gifts.

Making It Sound Like Fun

In 1949, MIT began recruiting kids into what they called the “Science Club.” They made it sound exciting. There were trips, treats, and even a chance to leave the school grounds.

Charles Dyer, who joined at age seven, said they gave him a Mickey Mouse watch. “They made me feel special,” he recalled during a Senate hearing decades later.

Another boy, Austin LaRoque, was thirteen when he joined. He said they were told it would involve taking vitamins. The children didn’t know they were being experimented on. “We figured, hey, we get to go places,” he said.

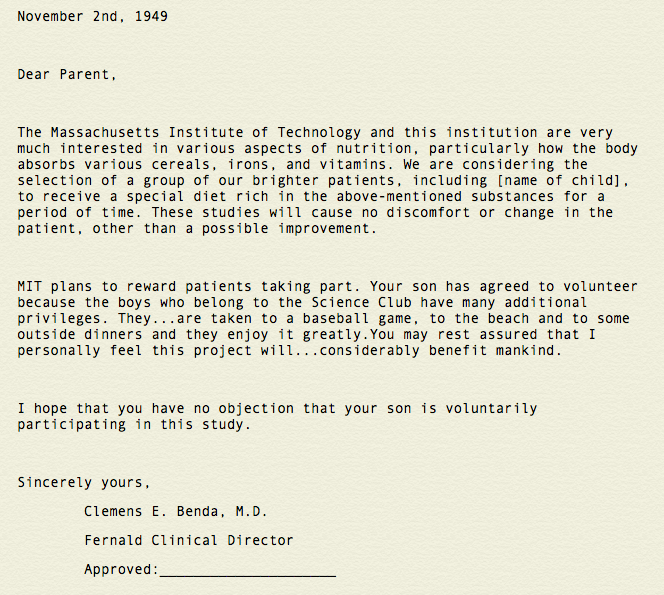

Some parents got letters about the club. But many had long since cut ties. And the letter did not say anything about radioactive materials or medical testing.

Years later, LaRoque said he had to sign his own consent form. “I couldn’t read or write back then,” he admitted. “I just did what I was told.”

Cereal, Milk, and Radioactivity

Once the kids were in the club, the real experiment began. Researchers fed them large amounts of Quaker Oats cereal mixed with radioactive iron. Then they tracked how much iron their bodies absorbed.

The findings worked in Quaker’s favor. They showed that oatmeal helped the body absorb iron just as well as farina, the base for Cream of Wheat. That claim later appeared in Quaker’s advertising.

Later, the experiments shifted to calcium. Thirty-six children were given milk with radioactive calcium tracers. The goal was to see if plant-based cereal interfered with calcium absorption.

Once again, Quaker got the result it wanted. The combination of oats and milk was found to be nutritionally sound. The study showed that oatmeal did not block calcium intake.

But the most invasive study was still to come. Nine boys were given injections of radioactive calcium. Researchers wanted to track what happened when it entered the bloodstream.

That final test helped advance research on bone health. But it was done without informed consent. The boys were never told what they were being given.

No Thanks, No Follow-Up

When the testing ended, MIT moved on. The children were never checked again. The researchers never came back to Fernald.

But they did pass their findings to Quaker Oats. The company used them to claim that their cereal was “high in iron.” No one mentioned how those findings were obtained.

For years, the children had no idea what had been done to them. The paperwork stayed hidden in research archives. Until someone went looking.

A Reporter Finds the Files

In 1993, journalist Scott Allen of the Boston Globe stumbled onto the story. He found records of secret studies done on Fernald children. The documents named MIT and Quaker Oats.

His article, “Radiation Used on Retarded,” ran the day after Christmas. It caused an immediate outcry. People wanted answers.

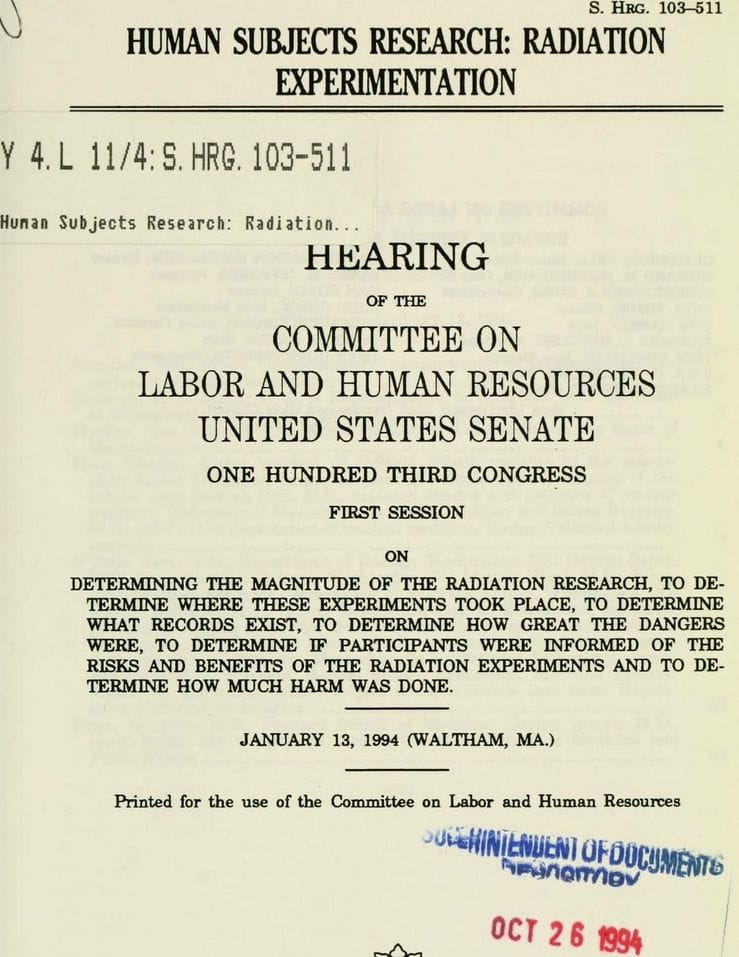

The government opened an investigation. The Senate held hearings. The focus quickly turned to how much radiation the children had been exposed to.

David Litster, then vice president of research at MIT, tried to downplay the numbers. He said the doses were small. “About 170 to 330 millirems,” he testified. “Roughly equal to 30 chest x-rays.”

For the calcium tests, he said the dose was even smaller. “Less than 12 millirems,” he claimed.

To put it in context, a resident of Boston might absorb 300 millirems of background radiation over a year. But that wasn’t the point.

It Was Never About the Dose

Radioactive tracers were common in medical research. Scientists still use them today. What made the Fernald case different was the way the studies were done.

No consent. No information. No choice.

Congressman Joseph P. Kennedy II called MIT’s letter to parents “deceptive at best.” There was no way to justify what had happened, he said, even if the radiation was low.

MIT’s defense leaned on history. In 1949, there were no formal rules about consent in research. The National Institutes of Health only introduced such policies in 1953. It wasn’t until 1974 that federal law required informed consent and review boards.

Still, Dr. Bertran Brill from MIT made an odd defense. He said Fernald kids were ideal subjects because they ate a lot of cereal. Under pressure, he admitted the truth.

“They shouldn’t have used a group that had no way to say no,” he said. “That was wrong.”

A Quiet Settlement

After the hearings, lawyers began searching for former members of the Science Club. Many of them were now elderly. Some had lifelong health problems.

In 1997, around 30 men joined a class-action lawsuit. They sued for $60 million, citing violations of their civil rights.

A task force in Massachusetts reviewed the case. Their conclusion was blunt: the consent forms were not clear. Families could not have made an informed decision based on the information they were given.

MIT still denied any wrongdoing. They said their researchers followed the standards of the time. But to avoid a long court battle, they agreed to settle.

MIT and Quaker Oats paid $1.85 million. That came out to about $60,000 per person—if that. Most of the money went to legal costs and fees.

David Litster brushed it off. “That’s like tuition for 20 students,” he said. He added that he himself had been exposed to more radiation at shoe stores as a child.

But the Damage Was Not Physical Alone

The real harm wasn’t just the exposure. It was the betrayal. The children were misled, used, and then forgotten.

One letter to the New York Times summed it up: “It was contaminated by ethical doubts,” the writer said. The moment you remove consent, you step onto a slippery slope.

A Harvard professor put it plainly. “We can do good science and still be honest,” he said. “If we don’t, it comes back to haunt us.”

MIT’s Science Club promised young boys fun, treats, and attention. What it delivered was deception cloaked in data. And a legacy that still feels radioactive today.