Two weeks after he vanished, eighteen year old Zebb Wayne Quinn finally showed up again in Asheville. Not in person. In the form of his small Mazda Protegé, sitting in a barbecue restaurant parking lot with its headlights still on and a surprise waiting inside.

A black Labrador puppy sat in the car, alive and healthy. Empty drink bottles were scattered around. A plastic hotel key had been tossed on the seat. A jacket that no one in his family recognized lay inside. On the rear window, someone had drawn a pair of lips and punctuation in bright lipstick.

His mother, grandmother and sister all worked at the nearby hospital. The car seemed almost placed under their noses, as if whoever left it there wanted one of them to find it first, to feel the shock before anyone else did.

A quiet kid with a simple plan

Before the car appeared, Zebb’s life looked almost painfully ordinary. He was eighteen, still living at home, working in the electronics department at Walmart on Hendersonville Road, and talking about joining the military once he had a little more experience under his belt.

He collected Star Wars figures, hung out with coworkers, and took his shifts seriously. Friends described him as shy, kind and a bit naive. He was close to his mother and sister. He did not drink heavily, did not use drugs, and did not seem eager to burn his old life down and disappear.

On Sunday, 2 January 2000, he finished his evening shift at Walmart and stepped into the parking lot around 9 p.m. A coworker, twenty one year old Robert Jason Owens, was waiting for him. They had plans to drive out and look at a used car Zebb wanted to buy.

They each drove their own vehicle. Owens followed behind as they left the lot. For a while, everything moved along quietly through Asheville’s winter streets. Then something interrupted that smooth line in a way that still bothers investigators twenty five years later.

The page that changed everything

The two men stopped at a gas station convenience store a short drive from Walmart and went inside to buy sodas. Surveillance footage later showed them there around 9:15 p.m., just two young guys at the end of a shift. Nothing about the footage hinted at what was coming next.

According to Owens, when they left the station, Zebb signaled him to pull over. Zebb told him he had been paged. Phone records later traced that page to the number of his aunt, Ina Ustich, even though he barely spoke to her. She would insist she never sent that page.

Owens said Zebb walked to a nearby payphone to call back and was gone for about ten minutes. When he returned, Owens later told police, his usually mild coworker looked frantic and agitated, as if he had just heard something that shook him. Zebb suddenly cancelled their trip to see the car and rushed back toward town.

Owens also claimed Zebb accidentally bumped the back of his truck as he sped away. It sounded like a minor collision. Yet just hours later, Owens appeared in an emergency room with a broken rib and a head injury that he said came from a separate car accident that same night. Police never found any record of that second crash.

The next afternoon, when Zebb did not come home, his mother filed a missing person report. As far as she was concerned, something serious had happened between the parking lot and the moment he promised to come back. She never heard from him again.

Voices that sounded wrong

Two days after Zebb vanished, Walmart received a phone call. A man claiming to be Zebb said he was sick and would not be in for his shift. The coworker who answered felt uncomfortable. He had spoken to Zebb many times and thought the voice sounded wrong.

Police traced the call to the Volvo plant where Owens worked another job. Confronted, Owens admitted he had made the call and said he was only doing Zebb a favor. That explanation went straight into the file of things that did not make sense but could not be easily disproven.

Around the same time, detectives followed the pager number and landed on aunt Ina’s house. She said she had not been home at all when the page went out. Instead, she said she was at the home of a friend, Tamra Taylor, whose daughter Misty happened to be someone very important in Zebb’s last weeks. Misty and her boyfriend, Wesley Smith, were also there that night.

Later, Ina reported a break in at her home. A few items had been disturbed, frames moved, but nothing stolen. It looked to investigators like someone had wanted access to the phone line, not the jewelry box.

A crush with sharp edges

In the weeks before he vanished, Zebb had grown close to nineteen year old Misty Taylor. He confided in friends and family that he liked her and that she seemed trapped in an abusive relationship with her boyfriend, Wesley Smith. He also said Wesley had threatened him after learning about their friendship.

Police questioned Misty and Wesley. Both denied any role in Zebb’s disappearance. Officially, no hard evidence has ever tied either of them directly to what happened that night. Unofficially, detectives have always treated that small triangle of names as a cluster of pressure points in the story.

What makes the triangle more unsettling is how often the same people and locations appear. The odd page came from a number linked to a house where Misty was visiting. The car appeared near the hospital where Zebb’s family worked. The restaurant parking lot sat close to familiar roads and daily routines.

The car, the puppy and the lips

On 16 January 2000, fourteen days after Zebb left Walmart, his mother received a tip that his Mazda was sitting in the lot of Little Pigs Barbecue on McDowell Street. When police arrived, the headlights were still on. The driver’s seat had been pulled forward for someone shorter than Zebb’s five foot nine frame.

Inside, officers found the puppy, the unclaimed jacket, the scattered drink bottles and that hotel key that did not match any specific property. They also saw the lips and exclamation marks drawn on the rear window in lipstick, bold and strange and very deliberate.

Investigators believed the car had been staged there rather than abandoned in a panic. It sat near the hospital, near daily foot traffic, near people who knew Zebb’s name. It looked less like a forgotten vehicle and more like a message from someone who enjoyed sending puzzles instead of plain threats.

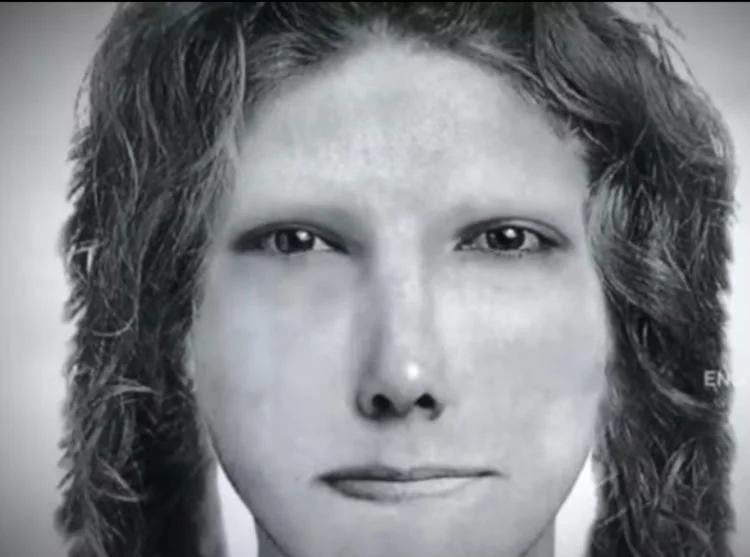

A local couple later called in to say they had seen the Mazda being driven downtown before it turned up at the restaurant. They helped police build a composite sketch of the driver, a woman with straight hair and a calm expression who did not look distressed or hurried.

Detectives later noted that the sketch bore a strong resemblance to Misty Taylor, though no one has ever proved she was in that car. Misty has consistently denied it. The woman in the drawing has never been identified with certainty.

A case that refused to move

For years, the investigation circled the same cluster of facts. Zebb left his shift with Jason Owens. He received a page that likely came from a house connected to Misty. He left in a panic, telling no one what he had heard. His coworker turned up injured with a story that never quite fit.

Police came to see Owens as more than a helpful friend. They executed a search warrant at his property in 2007 and publicly named him a person of interest in what they now described as a likely homicide. Still, no charges followed. Without a body or clear forensic evidence, the file grew older and heavier.

In 2012, the television show Disappeared featured the case, and later podcasts and YouTube channels would pick it up. The attention kept Zebb’s photo circulating but did not pull out the missing piece. His mother and sister kept calling detectives, kept answering media questions, kept a room ready that never needed to be changed.

The neighbor who turned killer

Then, in 2015, another crime blew the case wide open again. Owens was arrested for killing his neighbors, Cristie Schoen Codd, a chef who had appeared on Food Network, her husband J.T. Codd, and their unborn child near Leicester, not far from Asheville.

Investigators searching his property found items belonging to the Codds in a dumpster and human remains in a woodstove. Owens ultimately pleaded guilty to multiple counts, including dismembering human remains, and received a sentence that effectively keeps him in prison for the rest of his life.

Once his name hit headlines as a convicted killer, detectives looked hard at the old files. They obtained new warrants and went back over his land, digging through concrete and soil and strange white powder, pulling out bits of fabric, leather and hard fragments that raised questions but did not deliver a confirmed identification.

The public suddenly saw Owens not as the slightly awkward coworker from a cold case, but as someone capable of extraordinary violence. For Zebb’s family, the Codds’ tragedy meant something bitter. It suggested their suspicions about Owens might always have been right, and that authorities had simply never had enough evidence to act.

A murder charge without a body

In July 2017, a Buncombe County grand jury indicted Owens for first degree murder in the death of Zebb Quinn. The charge came seventeen years after the teenager left Walmart for what was supposed to be a short drive to see a car.

Police did not publicly reveal every detail they had gathered, but they described the indictment as the result of years of work, new interviews and what they believed were critical pieces uncovered during the Codd investigation. For the first time, the state said, on paper, that someone had killed Zebb.

Trials stalled and drifted, delayed by scheduling problems and later by the pandemic. While the wheels turned in the background, Zebb’s family aged. His friends built lives. The case moved from active mystery to haunting backstory for any true crime segment about missing people in small cities.

The story Owens finally told

In July 2022, more than twenty two years after Zebb vanished, Owens entered a plea. Instead of going to trial for first degree murder, he admitted to a lesser charge: accessory after the fact to first degree murder in Zebb’s case. The plea formally acknowledged that Zebb had been killed, even though his body had never been found.

Through his attorneys, Owens offered a version of events that shifted the spotlight toward family and that old love triangle. He said his uncle, Walter “Gene” Owens, had shot Zebb in Pisgah National Forest after being hired by Wesley Smith, the boyfriend who allegedly resented Zebb’s relationship with Misty.

Owens claimed he and Zebb were lured there under the pretense of meeting Misty, only to find his uncle waiting instead. In this story, Gene pulled out a .22 rifle, killed Zebb, dismembered the body and burned the remains, and Owens later helped cover it up. Gene had died in 2017, conveniently beyond the reach of any future indictment.

Prosecutors accepted the plea but publicly admitted skepticism. They did not have enough physical evidence to prove every detail, and they knew that Owens had already shown himself willing to lie and manipulate. Even so, the conviction legally settled one thing: the state now officially recognises that Zebb was murdered.

What remains after a plea

For his family, the plea landed in a strange emotional middle ground. On one hand, they finally heard a courtroom acknowledge what they had believed since early 2000, that their son and brother did not simply run away. On the other, they still did not get what most families want most: a body to bury and a clear, tested story.

Owens’ account placed the blame on a dead uncle and a jealous boyfriend who has never been charged with anything in connection to the killing. Misty has never been charged either. The supposed shooter cannot be questioned. The alleged instigator walks free, unconvicted, and denies any role in ordering a murder.

Police have said carefully that they still believe other people in the Asheville area know exactly what happened that night and have kept quiet. That kind of silence can last a long time in small communities, especially when violence and loyalty sit close together in long held memories.

The unanswered questions are not subtle. Who actually sent the page that changed Zebb’s plan at the gas station. Who drove the car with the puppy and lipstick and abandoned it near the hospital. Whether the love triangle motive is real or just another of Owens’ self serving stories.

What exists, in the end, is a narrow strip of certainty. An eighteen year old left work to chase a small dream of a better car and a more independent life. A coworker with a history of lies and now proven violence walked part of that road with him. Somewhere between the Walmart parking lot and Pisgah forest, the rest of his story was taken away.

A Reddit post brought me here

What were the contents of the page mentioned?

Great article.