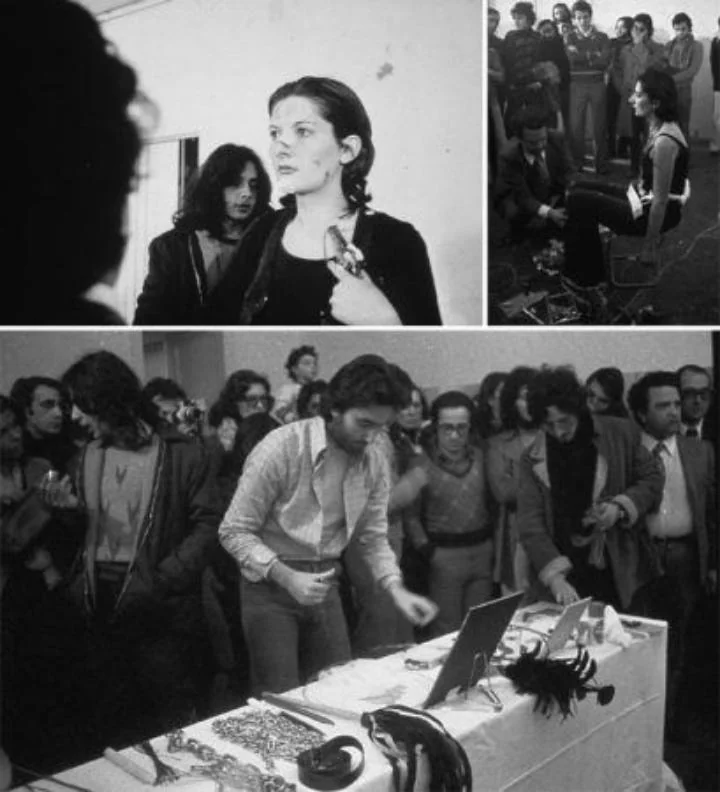

In 1974, Marina Abramović staged a performance called Rhythm 0 that pushed the boundaries of art and psychology. It took place in Studio Morra, Naples, and lasted for six hours.

She stood still beside a table holding exactly 72 objects. Some items were playful, like honey and flowers, while others were brutal, including razor blades and a loaded gun.

Her only instruction said: “Use these objects on me as you wish. I am the object. During this period, I take full responsibility.” She vowed not to resist.

Many people call this the world’s most disturbing piece of art. It forced spectators to examine their moral compasses because they faced no consequences for whatever they chose to do.

Abramović was already known for her willingness to risk her own safety in the name of art. Earlier performances in her Rhythm series had seen her testing the limits of pain.

Rhythm 10, for example, involved twenty knives. She stabbed the spaces between her fingers repeatedly, drawing blood when she missed. Then she replayed a recording, syncing new cuts with old ones.

Through that piece, she noticed how the audience’s energy could affect her physical state. She realized she could tap into that dynamic for more extreme experiments.

Another performance, Rhythm 5, involved a large wooden star soaked in gasoline. She lit it on fire and lay in its center, breathing the smoke until she passed out.

The audience eventually realized she was unconscious only after parts of her clothing caught fire. They pulled her out, preventing more severe harm. But the risk was already evident.

That star represented communism in Yugoslavia, her home country, hinting at political and social commentary. But Abramović’s real signature was testing human reactions to vulnerability and danger.

All of these experiments led her to the chilling night in Naples, 1974. Rhythm 0 took these ideas to their most unsettling extreme, removing her final shred of control.

She was not simply risking injury. She was allowing perfect strangers to decide whether she should be humiliated, harmed, or even killed—without moving a muscle to stop them.

For the first hour or two, spectators treated her gently. They posed her arms, fed her small bites of cake, and placed a rose in her hand. There was caution in the air.

But as time passed, curiosity won out. People realized she really wasn’t going to resist. She was standing there, passive, with no intention of self-defense.

That moment marked a turning point. Onlookers who had been shy or respectful felt emboldened, ready to push the performance further than Marina’s earlier works had ever gone.

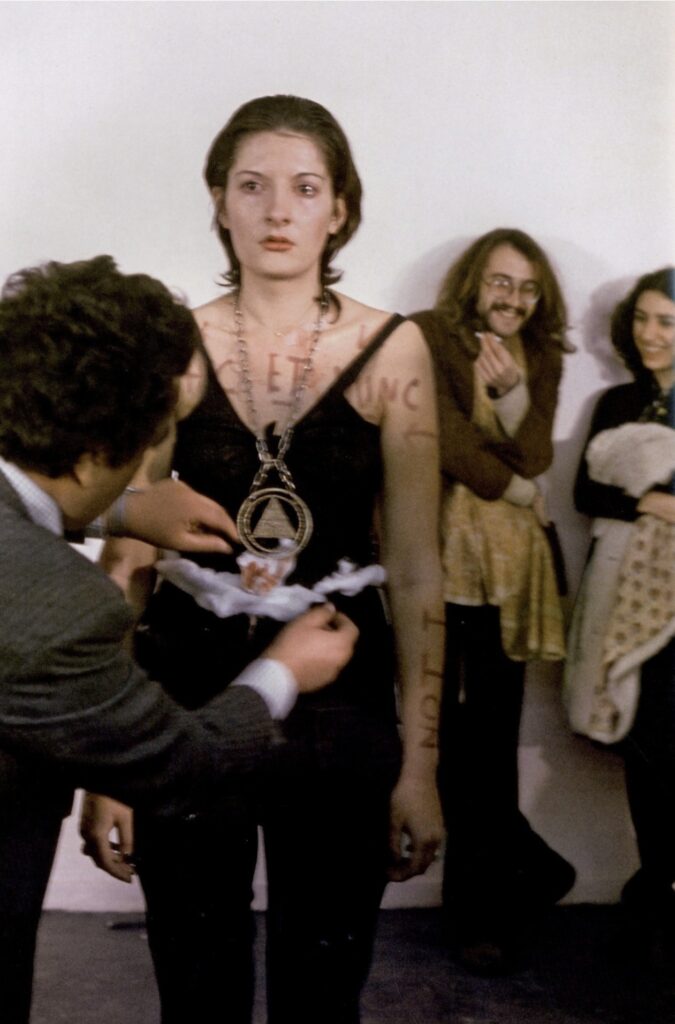

They used razor blades to cut off her clothes, exposing her naked body. Blood trickled from minor cuts, leaving red streaks on her skin. She did not flinch.

Some pressed thorns into her flesh. Others wrote on her bare skin. A few mockingly wiped away her tears, only to do something cruel moments later.

At one point, she was laid on the table, and someone stabbed a knife between her legs, close enough to be threatening. Still, she refused to move or object.

A man tried to assault her sexually, but a handful of audience members stepped in. They stopped him, which showed not everyone joined the mob mentality.

Abramović later called the final hours “pure horror.” People drank her blood, cut her neck, and tried to see how far they could push their power over her body.

Then the gun was introduced. One participant placed the bullet inside and set it in her hand, curling her finger around the trigger, aiming the barrel at her own head.

She still wouldn’t resist. Someone else pointed the loaded gun at her forehead, testing if she would beg for mercy. She gave no sign of fear or protest.

Accounts describe how a fight broke out among the crowd when the gun was involved. Some argued it had gone too far, while others seemed eager to continue.

By the end, she was bloody, naked, and trembling. Yet she remained stoic, maintaining her vow of stillness and silence. It was a grim testament to her commitment.

When the clock finally hit six hours, the performance ended. Abramović then took a single step forward, moving of her own will for the first time that evening.

That tiny motion shattered her “object” status. The same people who had touched or hurt her now ran away. They could not meet her eyes once she became human again.

She walked toward them, hoping for some acknowledgment or reaction. Instead, they fled, unwilling or unable to confront what they had done during her six hours of passivity.

Later, she reflected that if the performance had continued longer, the crowd might have killed her. In her words, “If you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you.”

Rhythm 0 is seen as one of the most disturbing pieces of art because it exposes the hidden potential for violence in ordinary people. It wasn’t staged. It was raw and real.

The tension came from the knowledge that nobody would face legal or social consequences for harming her. With that barrier removed, cruelty surfaced in the unlikeliest of places.

Some compare it to the Stanford Prison Experiment, where volunteers quickly adopted abusive roles. Others recall Milgram’s obedience studies, where participants shocked a stranger at an authority figure’s command.

Yet Abramović’s version didn’t require an official lab or academic setting. She simply stood in a gallery, inviting everyday folks to act on their darkest whims.

This brutality didn’t reflect an isolated group of criminals. These were typical visitors at an art event. Her performance forced them to question the line between viewer and perpetrator.

There is also a stark gender component. Abramović has noted that women often face expectations of passivity. Rhythm 0 highlighted how dangerous that forced passivity can become.

She also wanted to explore how the body turns into a site for power struggles. By becoming an “object,” she turned herself into a canvas for others’ impulses.

Many watchers felt shocked by how quickly normal civility vanished. Even those who started with small pranks escalated into more harmful acts, fueled by group psychology.

When asked about the experience, Abramović said she was genuinely terrified at times. But she refused to break her own rules, which forbade any form of resistance.

Her earlier stunts with knives and fire had been risky, but at least she maintained control. During Rhythm 0, she handed every ounce of control to her audience.

This work also echoes the violent aspects of cultural or political oppression. She had already drawn parallels to communist Yugoslavia in Rhythm 5, but Rhythm 0 took it further.

No single culture can claim a monopoly on cruelty. In the heart of Naples, far from her home, she found everyday people who would cross lines once the rules disappeared.

After the show, she walked away from Studio Morra covered in cuts and bruises. The crowd that had cut and humiliated her refused to confront what they had done.

Her experience shows how easily empathy can be cast aside. Once individuals see someone as an “object,” monstrous acts can feel strangely acceptable in the absence of consequences.

These insights resonate with the Freedium article, which highlights that the performance was meant to reveal “facets of humanity and womanhood,” as well as our collective potential for cruelty.

It also underlines her earlier pieces, such as Rhythm 10 and Rhythm 5, which tested physical endurance and unconscious states. But none reached the brutality of Rhythm 0.

By the time the gun appeared, it was evident people were not just exploring art—they were flirting with real violence. If not for internal disagreements, a tragedy might have occurred.

Her final walk toward the audience remains one of the most haunting moments in performance art. It shamed those who had once treated her like a lifeless mannequin.

Abramović has since become a legendary figure in contemporary art. She has continued to push boundaries, but Rhythm 0 stands out as a defining commentary on human darkness.

Critics still call it “the most disturbing piece of art” because it leaves no room for comfortable distancing. It forces viewers to ask, “What would I do in that situation?”

This question lingers because the performance was interactive. Observers were part of the piece. Their choices shaped the outcome, revealing the fragility of moral restraint.

Some wonder if a modern audience would behave differently. But the Stanford Prison Experiment and other real-world incidents suggest that circumstances and social permission can erode empathy anywhere.

Rhythm 0 thus serves as a timeless reminder: the line between compassion and cruelty can be frighteningly thin. Without accountability, even normal people can inflict unimaginable harm.

Abramović’s naked, wounded form symbolized everything we prefer not to see about ourselves. By not resisting, she forced everyone to grapple with their own capacity for violence.

In a world that sometimes rewards aggression, her performance begs us to question whether we’d speak out or stay silent when confronted with vulnerable lives at risk.

Art historians praise Rhythm 0 for its stark honesty. It transcended theatrical shock value to become a genuine test of conscience. That raw tension still resonates today.

Discussions continue about whether the performance was ethical, but Abramović’s point was that no “safety net” existed. That void exposed something real about human nature.

Her actions tapped into deep fears about how society treats women, minorities, or anyone deemed powerless. The invisible dynamics of domination became painfully visible that night.

Decades later, Rhythm 0 remains pivotal in debates on performance art, violence, and morality. Other artists have cited it as an influence on their own explorations of power and vulnerability.

Ultimately, it is a mirror, reflecting the audience back at itself. Some saw kindness, trying to protect her. Others witnessed their own potential for harm, unleashed in a few short hours.

The memory of Marina’s battered silhouette stepping forward, eyes open and spirit unbroken, stands as a final testament. Even after everything, she reclaimed her identity from the crowd.

“If you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you,” she famously said. These words capture the heart of Rhythm 0, an unsettling glimpse into human capability.

It is this raw confrontation with the darker corners of human nature that explains why many consider Rhythm 0 the world’s most disturbing piece of art. It was a dark shock of reality.

That tension—between empathy and cruelty, bravery and fear—still reverberates through art discussions. We see echoes in modern society, where anonymity often leads to callous actions online or off.

Abramović managed to show us, without words, how easily decency can crumble. Her silent endurance became the catalyst for a terrifying spree of aggression by everyday people.

In the end, her work compels us to ask: Could we remain gentle in a setting that absolves us of guilt? Or would we become what we fear most?

Rhythm 0 provides no easy answers. Its lasting impact comes from holding a mirror to the darkness inside us. That mirror is unsettling because it reveals both cruelty and conscience.

Decades later, this performance stands as a milestone in art history. It challenges viewers to reckon with the fragile line that separates restraint from violence and apathy from empathy.

Even now, references to the event flood discussions on the nature of performance, audience participation, and the moral responsibilities we owe each other in any shared space.

Abramović’s ordeal in Naples endures as a grim wake-up call about human behavior. It warns that sometimes all it takes is permission and opportunity to release hidden savagery.

Yet, it also hints at hope: a few people tried to save her or stop the worst violations. That suggests our capacity for empathy endures, even in dark situations.

The tension between those two forces—care and cruelty—echoes through time. Rhythm 0 remains a vivid reminder that each individual must choose which side of human nature they will embrace.