Miami’s NW Second Avenue has a pool hall that smells of beer and smoke, where names rarely matter and stories float above felt tables. An old man told people that he once fought Muhammad Ali and nearly won. Laughter followed his shadow punches, and quiet returned when he sat.

A New Hampshire car salesman named Stephen Singer loved collecting things connected to Ali. He kept an illuminated X-ray on his office wall that showed the famous broken jaw. He explained that he wanted signatures from all fifty men who fought Ali, a complete roll call of opponents.

Singer said the first thirty-five names arrived easily with help from a professional autograph hunter. Progress stopped after that, so he searched alone. He started visiting old gyms, paging through public files, and phoning anyone who might remember brief careers that flickered and disappeared in distant rings.

He described finding one man who had traded boxing for a European carnival, then locating a notarized letter from a fighter who later worked as a Mafia hit man. A rabbi in a small Argentine town helped retrieve documents for a fighter who died in 1964. That made forty-nine.

One remained. Singer wanted to find Jim Robinson, who fought Cassius Clay in Miami Beach on February 7, 1961. An old wire note claimed Robinson came from Kansas City, so Singer called a local feature writer. Almost nobody had ever looked for Robinson. He felt real only after someone noticed absence.

The night of the fight, Robinson arrived at the Miami Beach Convention Hall as a last-minute replacement because scheduled opponent Willie Gullatt never appeared. The day before, Ali had sparred heavyweight contender Ingemar Johansson, moving fast and landing clean punches that impressed witnesses. Opinions of the young contender changed sharply.

Robinson was lighter by about sixteen and a half pounds. He rushed in with wide shots while Ali waited, slipped the punches, then struck with quick combinations that dropped Robinson. The referee reached nine and stopped it. Reporters later judged the matchup a clear mismatch. The bout lasted ninety-four seconds.

Three years later, Ali beat Sonny Liston in Miami to become champion, while Robinson lost to Jack Gilbert in a smaller hall the very next night. Robinson already seemed to fade from notice. He kept fighting through 1968, losing more often than he won, then slipped away from public view.

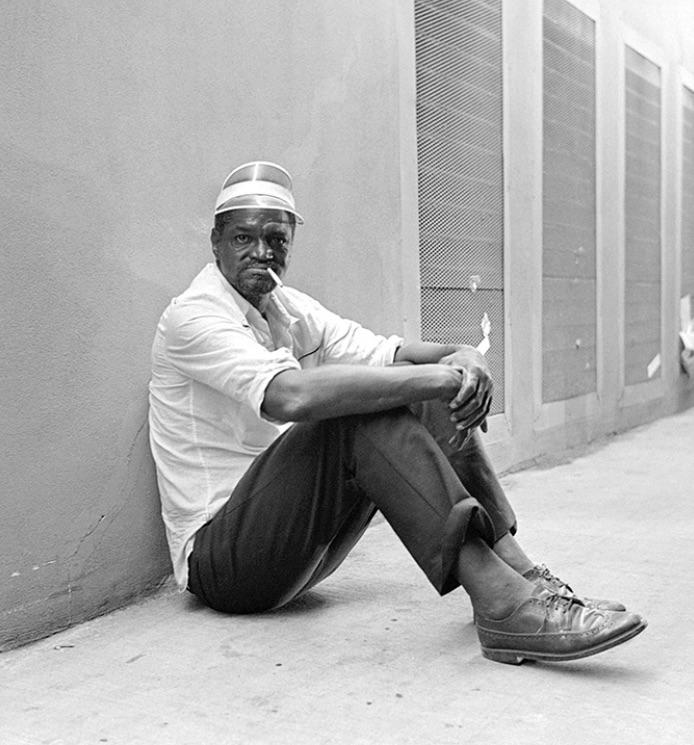

A single sighting surfaced in 1979. Sports Illustrated sent photographer Michael Brennan to find Ali’s earliest opponents, and people in Miami identified Robinson as “Sweet Jimmy.” A brief note said he lived on veteran’s benefits, believed he was born around 1925, and claimed his armed-robbery conviction had been wrongful.

Brennan’s photographs showed a haunted face and a jutting jaw that suggested missing teeth. Thick eyebrows sat under a visor’s shadow, with a long scar on the left cheekbone. One frame caught him against a Winn-Dixie wall, another on railroad tracks with Miami’s skyline behind him, unsmiling throughout.

Brennan worked Friday night and Saturday morning. He later recalled handing the old fighter twenty dollars as they stood by the tracks. Robinson walked away on the ties without turning around, and he asked that word be passed along that he was not doing well, a message meant for memory.

Most people leave paper footprints. Records stack up around addresses, vehicles, taxes, marriages, and divorces, and search engines gather enough detail to prove a life happened. The reporter who joined the hunt first believed finding Robinson would take a day or two, using those tools that usually solve such puzzles.

Six years passed. The searches found many James or Jimmie Robinsons near Overtown who did not match the fighter. One man was shot in 1984, another died from a gunshot in 2007, and another was beaten under an overpass in 1991, all carrying fragments that did not fit correctly.

The medical examiner’s office listed hundreds of unidentified deaths in Miami since 1980, and any could have been Robinson. The reporter ran hundreds of database queries and called boxing people, Angelo Dundee among them, then contacted the V.A., the military records center, Social Security, the police union, and cold-case teams.

None of those paths turned up an African American J. Robinson of the right age and description. Florida corrections had no matching custody records. The reporter decided he had been searching as he would for himself. Robinson’s life moved off the grid, outside the trail that paper and numbers usually leave.

The restart began at Miami Beach’s Fontainebleau Hotel. A bellhop named Levi Forte had once fought professionally, sharing rings with champions before spending decades helping guests. Many tourists never knew that Beau Jack had shined shoes downstairs years after headlining Madison Square Garden many times, another champion hidden in plain sight.

The reporter showed Levi a photograph. Levi studied the beard, lashes, and jawline and said the image matched Robinson. He remembered last seeing him near the 5th Street Gym decades earlier. Recognizing the name briefly gave Robinson weight again. For a moment, someone speaking it made him feel real and present.

Before the reporter drove away, Levi leaned to the window and offered a detail he wanted recorded. He had gone ten rounds with George Foreman on December 16, 1969, the first to do so, and he wished the story to carry that fact forward, a small proof against forgetting.

The search turned into Overtown, close to the arena where the Miami Heat play, and the blocks shifted tone quickly. Boarded windows gave way to empty lots, and watchers tracked every unfamiliar car. A police officer even suggested rolling red lights for safety. Entry into those streets never went unnoticed by anyone.

In the 1960s, Overtown held black hotels and clubs where stars performed after shows on the beach. Musicians who could not stay on Miami Beach saved their fiercest sets for these rooms. Promoter Clyde Killens booked legends, including Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, Count Basie, B. B. King, and John Lee Hooker.

That vibrant scene is gone. A filmmaker who documented Ali’s Miami years described side streets that felt cut off from the larger world, humming with need and thin on hope. The reporter posted fliers with a photograph and a local number, then left copies in shops and emailed church offices likely to notice.

Three days later, calls began. A man named Melvin Eaton said he had known Sweet Jimmy for years and last saw him five or six years earlier. He said Robinson shadow boxed, told people he had fought Ali, and believed that he should have been the greatest, a refrain repeated constantly.

A woman named Brenda said she saw him daily near 12th Street and Second Avenue, where he asked passersby for a dollar for soda or beer. When asked to put him on the phone, she later said he had walked away again, her account hovering between help and uncertainty as the minutes passed.

The reporter returned to Miami. A private investigator suggested Camillus House, a shelter on Overtown’s edge that many unhoused residents pass through eventually. Outside, a couple pushed a stroller toward the door, and another person carried a baby rattle inside, everyday objects crossing a threshold that often marks survival for the night.

At the desk, a staff member named Patricia studied the flier and seemed to sag. She said she never forgot faces and that the man pictured was homeless. She did not know whether he remained alive. Her words mixed possibility with dread, a feeling like finding a door that might open too late.

THE WORLD WHERE NO ONE EXISTS

Overtown’s old pool hall stands boarded, its stories locked inside. The past feels erased. People once remembered a white father and son who fixed watches here until polio struck the son in the fifties. Promoter Clyde Killens later ran it. Sharks visited. Jackie Gleason reportedly sang atop tables.

It is the last building on the block. Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s fight doctor, kept an office next door until the 1980 riots burned it. Crime crowded the avenue. Police were called often. Officers once found a stolen motorcycle hidden in back. Fire and demolition cleared the rest away.

Killens died in 2004, after heroin took his son. In his final years, people said he shut the shades and stopped listening to music. The city condemned the hall in April 2005. His daughter lost the property after bad business moves. It has stayed empty since that order.

Rolling metal doors are locked tight. Cinder blocks choke the upstairs windows. Boards carry the number 920 in paint. The current owner allows a look inside. The tables are gone. Walls are torn out. Floors are ripped up. Turquoise paint nods to Dolphins colors and Booker T. Washington High.

A toilet sits in the open. A back room holds a homeless person’s basket of clothes and a cardboard bed. Trash piles in a corner with a single shoe resting on top. A welcome mat lies nearby, both gentle and cruel. The searchers find nothing that belongs to Jimmy.

Overtown surrounds the shell, cut north and south by Interstate 95, and east and west by Interstate 395. The concrete roof that roars above serves as a daily reminder of what the neighborhood was, what it became, and the reasons. It is a map of loss and survival.

Interstate construction in the late sixties forced thousands from homes and erased a busy business district. The roads also cut the area away from Miami. Population fell from forty thousand to just over ten thousand. A barter economy took hold. A beer might buy a bath. Medicine might buy shelter.

The ZIP code ranks among the poorest in the nation. Florida lists more registered sex offenders here than any other ZIP. People speak of a dumping ground for addicts, predators, and untreated illness. In the shadow of downtown’s towers, many live invisible lives, with few records and fewer expectations.

At Northwest Third Avenue and Eleventh Street, a small group huddles beneath Interstate 95 and scans for police. One man says officers tell them to go home and that life here feels like martial law. Suspicion lingers. Outsiders get watched closely. Trust is rationed and takes time to borrow.

One woman’s arms are ridged with scars that look like crash wounds. Locals later explain these came from infections after years of heroin use. She has seen the fliers and asks for help finding her father. She offers his name, hoping to rebuild a past that would make her whole.

People under the overpass talk about Sweet Jimmy and about neighbors who simply vanish. The woman urges friends to list an emergency contact so someone will know a name if a person disappears. They speak softly under the tire whine, where waiting becomes habit, and time stretches without mercy.

They wait for the next hit, the next drink, the next simple meal, and the next green mattress at Camillus House. They wait to be told to move along. They imagine morgue tags that read remains unknown. The concrete gives shade, and sometimes a breeze breaks the heat like mercy.

It takes time, but the reporter earns trust in Overtown. Social worker Al Brown introduces people and opens doors. Smiles replace stares and the neighborhood becomes a guide. One morning, Al walks into a Northwest Third Avenue barbershop and asks if anyone remembers a fighter named Sweet Jimmy.

A voice from a back room answers that Sweet Jimmy is dead. An older barber steps forward and introduces himself as Payne. He says he used to cut Jimmy’s hair, as did the man in back, especially before Jimmy stayed at shelters. Payne says Jimmy drifted into drugs and streets.

Payne says Jimmy held no steady job. He relied on anyone who knew him from times past. Payne mentions a friend named Mr. Big. He lives nearby in a turquoise building across from the empty lot where the Harlem Square club once stood, where Sam Cooke recorded a live album.

Al knocks until Mr. Big steps outside and blinks in the sun. Mr. Big says he thinks Jimmy left town a long time ago. Al asks when. Mr. Big answers that it was back in the eighties. Certainty is hard here. People remember moments. Timelines slide and blur.

The reporting begins to settle into three lessons. First, most locals saw Jimmy but did not know him. Many never knew his last name or hometown. Almost no one watched him fight Ali. To many, he moved through life like a sketch on paper instead of a full figure.

Second, elders fell into two camps. Some held regular jobs and stability. Others survived by hustles. Both camps knew Jimmy, but as years passed he spent more time with the hustlers and less with the working old-timers. Organizer Irby McKnight arrived the year Jimmy stopped fighting and remembered first impressions.

McKnight said Jimmy used to be loud and obnoxious, yet well dressed. Irby joked about where the man found such old suits. People told him the man was Sweet Jimmy who had fought Muhammad Ali. The past traveled in whispers. The details followed later, if they followed at all.

The third lesson came slowly. The helpers themselves wanted to be part of a wider world. By guiding the search, they were seen and valued by someone from outside. The work gave shape to their own lives. As long as they helped look, they felt present in the story.

Al and Mr. Big ride through every Overtown street and point to vanished places. Flop houses, short-order counters, and little clubs are gone. Wrecking balls, riots, and fires erased them. Jimmy outlived his neighborhood until only the pool hall stood. Few people remain who truly knew him well.

Al says a man named Shorty who once worked at the racetrack would know more. Mr. Big agrees and says Shorty watched Jimmy fight. The next day, Shorty Brown steps outside wearing a faded hospital bracelet. His skin hangs loose, and his words carry the rhythm of practiced memory.

Shorty says if Jimmy died, it did not happen here. If it had, everyone would know. He describes Jimmy as a hustler who played an angle with a belt and a pencil, a street game that nobody explains clearly. Shorty says Jimmy and a hustler called Sonny Red ran together.

Shorty remembers racetrack days at Gulfstream. He says the pair once angered everyone there and then landed in jail. The stories feel foggy but consistent. Sweet Jimmy liked the hustle. The details drift when asked twice, which happens often in Overtown where memories bend to the weight of years.

Calls from a man named Benny Lane add more brushstrokes. Kids mocked Jimmy’s heavy heel-first walk. He always carried cards and could run three-card monte. He laughed at his own jokes, even when others did not. He shadow boxed when friends shouted his name. One night a man punched him.

Benny says by then Jimmy could not fight back. Teeth kept failing. Drinking got heavy. His mouth looked ragged. They chatted about women, news, and the idea of home. Benny thinks Jimmy said he went to school in Kansas City. Jimmy sometimes disappeared for a month and mentioned a brother.

Benny describes kindness that tried to protect Jimmy from himself. Clyde Killens and others who profited from earlier fights watched over him. They cashed his check and handed out an allowance because gambling swallowed the rest. If a game started, Jimmy forgot about tomorrow and played like only now mattered.

As the car pulls away, Shorty runs beside and adds one fact. He says Jimmy was a disabled veteran who received an Army check each month. Shorty remembers the number as seven hundred forty dollars. Friends would gamble it away from him, with Jimmy promising more would come.

Mail for a Robinson still appears now and then at the pool hall address. Residents remember envelopes arriving irregularly. Benny thinks Jimmy sometimes used Killens’s address for documents and payments. The last letter showed up about a year ago. It offered no clear answer and only deepened the lingering mystery.

The stories keep flowing for anyone willing to listen. Most of them match. A few do not. One former opponent even claimed Sweet Jimmy was an impostor who never fought Ali. The reporter remains as sure as possible that this is wrong, while admitting certainty is difficult in this place.

Brenda, who first called and claimed to see Jimmy daily, later seemed high or confused or working a scam. Each twist suggests the search arrived too late. The man it sought likely slipped beyond reach, leaving only memories that feel sturdy at breakfast and uncertain again by nightfall.

The reporter keeps asking whether anyone watched Jimmy leave, saw his body, or attended a funeral. Nobody did. Someone once thought they kept a funeral program, but it vanished. People here prefer the story that he moved away. The darker alternative suggests he died unseen and rests in potter’s field.

Former manager James Hunt ran the pool hall from 2002 until it closed in 2005. He says many remember Jimmy but not the last day they saw him. In their telling, the man grew quieter, an outsider even here, and regulars kept him out of their pool games more often.

Hunt says whenever Jimmy had a little money he would play a few racks and claim he might have been one of the world’s best. People rolled their eyes. He said he could have beaten Ali but got in the way of the punch. Stories bend that line with time.

Hunt says Jimmy hated the word homeless and insisted he paid rent. Nobody remembers where, and the claim might have been pride. Jimmy arrived at opening time, earlier if Hunt came to clean. He helped sweep in exchange for games and a soda. He liked Pepsi and accepted leftover food.

On the first of each month, Jimmy played pool for fifty cents a rack and bought tobacco. He rolled his own cigarettes and joked that hand rolling let him make them as big as he wanted. Lenders lined up. Hunt warned the payout would leave nothing for bills or food.

WHERE THE HELL DID HE GO?

Hope drives any search more than databases or contacts or police. Overtown fights hope carefully, chipping at it a little each day until reality feels thin. People vanish for big reasons sometimes, and sometimes because a letter gets typed wrong in a newspaper story.

In the Miami library, the reporter scanned years of the local African American paper and spotted the scheduled opponent’s name for Ali’s 1961 bout. It was Willie Gullatt, not the misspelled version repeated by white papers and later books. The fix unlocked a phone book listing.

By afternoon he sat under a carport while Willie held court after losing a leg to surgery. Neighbors crowded close, cars honked, and people called him Big Willie. The scene made the reporter imagine an older Big Jimmy somewhere, telling neighbors about the night he fought Ali.

Willie joked about age and charm, teasing his audience with claims that still drew laughter. He said recovery had slowed his routine but promised it would improve soon. The reporter steered the talk to the night in question and asked why Willie did not climb into the ring.

Money decided it. Promoter Chris Dundee offered Ali eight hundred dollars and offered Willie only three hundred. Willie told them to forget it. Asked what he did instead, Willie smiled and described an Army duffel bag full of bootleg whiskey, then admitted he simply got drunk.

He described regrets that sharpen with time. He said he wished he had left liquor and certain relationships behind and believed a title shot could have come. He confessed he lacked the sense then that he carried now, and that the chance passed while he drank.

He accepted life as it was. The neighborhood planned a Labor Day barbecue and asked about Sunday. Willie grinned and said every day felt like Sunday to him now. The reporter left with answers and a clearer picture of the empty space where Jimmy should be.

Hope also kept Miami’s cold case detectives working. In a small office behind a green door, stacks of files represented lives like Sandra Jackson, reduced to a few lines about a body found in a vacant lot. Each folder waited for someone to restore a name.

Detective Andy Arostigui ran Robinsons through systems again and came up empty. An internal database that tracked nicknames for investigators turned up nothing under Sweet Jimmy. Two Daly City detectives visiting Miami listened as the reporter summarized fliers, pool halls, barbershops, Mr. Big, and Racetrack Shorty.

One detective said Miami felt like an island country where people turned to vapor. He said Jimmy’s world seemed to shrink until nothing remained. Another added that some men did not want to be found. The first said some finally decided to stop waking up altogether.

A woman poured tiny cups of café cubano around the bullpen while searches ended without a match. The reporter’s wish shifted from an interview to a body he could name. Andy predicted the answer would probably turn up at the medical examiner’s office rather than in police files.

The next stop introduced Sandy Boyd, the medical examiner’s cold case detective. She believed naming the dead was a human duty and worked tirelessly at it. Her office stepped up in terraces of files about people found alone, in fires, in canals, and sometimes both at once.

Another folder described a body that fell from an airplane’s wheel well. Another held a jumper from a half-built skyscraper. Elise Bobbitt checked records and said Jimmy was not in the city potter’s fields. Sandy narrowed possibilities to one unidentified man matching age and race since the pool hall closed.

A detox boat captain had pulled that body from the Miami River on December eighth, 2008. The remains still waited downstairs without a name. Sandy guided the reporter past the autopsy room and explained logistics. Cooler one received arrivals. Named bodies moved to cooler two after autopsy.

She said cooler three held the unidentified. Cooler four provided extra space. She opened the decomposed autopsy room, where the smell hit like spoiled dairy and strong cheese. This was where cooler five lived. On a table lay a man with sloughing skin and bleached patches across his body.

Farther down the hallway sat the bone room, marked M164. Metal shelves carried cardboard boxes filled with skeletons, including one from 1957 with a skull missing a few teeth. The newer boxes held remains found since 2004, all waiting for the simple grace of a name.

Sandy worked through the computer records again. Fourteen unidentified skeletal cases since 2005 could be eliminated for clear reasons. The last loose candidate was the river case. She opened the file and handed over a Polaroid, the face the only part visible under a blue shroud.

The man’s nose looked as if it had been broken. A slight overbite pushed the front teeth toward the bottom lip. There was no scar along the cheekbone. Case 2008-03065 was not Sweet Jimmy. The search returned to the streets, still without the certainty everyone wanted.

News arrived that pushed Jimmy further away. James Hunt said Racetrack Shorty had died three days earlier. Hints multiplied about a brother who came looking. Some said the brother took Jimmy home. Others said he never found him. The possible destinations began to cover the map.

People suggested Missouri, Clearwater, Saint Petersburg, and Tampa. Others claimed Louisiana or New Orleans. Someone said Belle Glade. Someone else said Texas. Another insisted the accent sounded like Georgia or Alabama. Ohio even appeared. He was everywhere and nowhere at once, present in rumor and absent in records.

Another fighter named Al Owens lived north of Liberty City. He looked at the flier and said the man in the photo was not Jim Robinson. He claimed he had fought Robinson twice and believed a street hustler nicknamed Sweet Jimmy later boxed under Robinson’s name.

Owens said he once saw the two men together. He said the hustler wore a familiar visor, carried the same beard and scar, and worked three-card monte. His story did not withstand scrutiny. The timeline did not fit the documentary record. Memory had taken pieces from him too.

To test competing claims, three photos traveled to a British lab at the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification. Two showed a young Jim Robinson in boxing gear. Another was Michael Brennan’s 1979 picture. Analysts compared features, camera angles, lighting, and aging effects, then issued a cautious conclusion.

The report found many similarities and no differences that aging or angles could not explain. On a six-point scale ranging from no support to strong support, they marked the identification as a four. The science lent support yet stopped short of certainty, matching the haze surrounding the entire search.

On a final Sunday morning, the reporter volunteered in the Camillus House kitchen and sliced ham and onions before heading out. At the exit he spotted Shelly, an eighty-year-old with milky eyes and a record stretching back decades. They had met the day before on the street.

The reporter bought two Pepsis and sat with him in the courtyard. Men and women gathered around a radio playing gospel and R and B. Towers of waterfront condos rose over the shelter, hiding the arena’s giant screen. The divide between worlds felt painfully close and visible.

Shelly said he missed Jimmy. He repeated dates he could not line up. He spoke about parents who left long ago, regulars who tried to stick together after the pool hall closed, and Clyde Killens making sure people ate. Then he described the day Jimmy finally left.

He said a brother had long planned to come. He claimed he watched the brother arrive and help Jimmy into a car. He remembered a handshake and a promise to return that never came. The details stayed the same today and yesterday, which made the story feel believable.

The courtyard shifted and the fragile world of Overtown pressed in again. A pigeon with tumors pecked at crumbs. A man searched under chairs for tobacco in discarded cigarette butts. Another leaned back and sang along. Shelly sipped his soda and said people disappeared like the wind.

The journey ended where it began, in Stephen Singer’s office. He walked the reporter to two huge frames holding photos, programs, tickets, and forty-nine signatures. A plaque read that Jim Robinson’s whereabouts were unknown and that the autograph was missing. Singer said he had moved on to other work.

The reporter wondered why he had not. The collection reminded him how boxing lives wander. Tunney Hunsaker spent nine days in a coma. Trevor Berbick was beaten to death with a pipe. Herb Siler went to prison for shooting his girlfriend. Tony Esperti went to prison for a Mafia hit.

Alfredo Evangelista went to prison in Spain. Alejandro Lavorante died from ring injuries. Sonny Banks died from ring injuries. Jerry Quarry died broke with dementia pugilistica. Jimmy Ellis suffered the same condition. Rudi Lubbers drank heavily and joined a carnival. Buster Mathis reached 550 pounds and died at fifty-two.

George Chuvalo lost three sons to heroin overdoses, and his wife took her life after the second. Oscar Bonavena was shot through the heart outside a Reno brothel. Cleveland Williams died in a hit and run. Zora Folley died mysteriously in a motel pool. Sonny Liston overdosed in Las Vegas.

The reporter told Singer that Liston’s was the saddest story. Singer said all of them were sad in their own way. Finding Jimmy might not solve anything. He might not remember. Many old fighters lost memory. Even that night’s headliners, Harold Johnson and Jesse Bowdry, were fighting memory now.

Johnson lived in a Philadelphia V A nursing home with good days and bad. Bowdry’s wife said he would not remember because he had dementia. Even Ali lived trapped inside illness, famous and hidden at once. Everyone paid costs for contact with fame, whether a little or a lot.

A writer named Davis Miller once described Ali staring from a high hotel window in Las Vegas in 1989 and whispering that everything was dust. He watched a fighter jet descend beyond the bright strip and said that from far enough up it was like people did not exist.