A gunshot in a Scientology stronghold

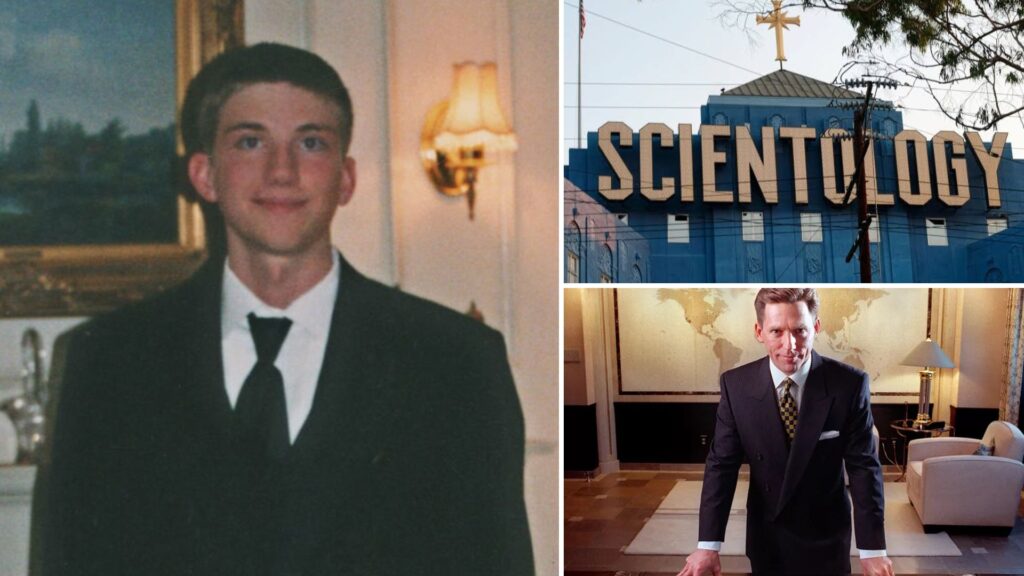

In February 2007, twenty year old Kyle Thomas Brennan travelled from Virginia to Clearwater, Florida, to visit his father. Clearwater served as the spiritual headquarters of the Church of Scientology and housed many of its key facilities.

Kyle’s parents lived apart. His mother, Victoria Britton, lived in Charlottesville and described her son as creative, gentle and socially anxious, with a love for art, computers and online gaming. He had mild depression and anxiety and took the antidepressant Lexapro.

He visited a local psychiatrist in Virginia in early 2006, received a Lexapro prescription and continued treatment through regular appointments. His mother has said he responded well, felt calmer and functioned better at school and work while on the medication.

Kyle’s father, Thomas Brennan, had moved to Clearwater and taken work with Scientology related entities. Court records describe him as a Scientologist associated with the Flag Service Organization, the church’s major base in the city.

Kyle arrived in Clearwater on 6 February 2007 and stayed at his father’s downtown apartment in the Colony House building. It stood within walking distance of several Scientology properties and offices in the city’s core.

The days before his death

During Kyle’s visit, his mental health and his medication became a source of tension. According to his mother’s later federal complaint, a Scientology “chaplain” urged Thomas Brennan to remove Kyle’s Lexapro because of the church’s opposition to psychiatric drugs.

Scientology literature and official statements present psychiatry as abusive and harmful, and the organisation strongly promotes non psychiatric approaches to emotional distress. Its advocacy group, the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, campaigns actively against psychiatric medication.

Kyle’s mother later told reporters and bloggers that Thomas locked the Lexapro in his car trunk, leaving Kyle without access to the medication that had stabilised him in Virginia. Court filings repeat that allegation and link the change to his worsening mood.

Friends and family accounts describe Kyle as increasingly distressed in those days. He phoned his mother, spoke about tension with his father and expressed a desire to return home. Travel plans for his return to Virginia stood only a short time ahead.

The night Kyle died

On the night of 16 February 2007, Kyle remained alone in his father’s apartment while Thomas went to work. According to police reports, Kyle died from a single gunshot wound to the head while inside the bedroom.

Clearwater police concluded that Kyle used a .357 Magnum revolver owned by his father. Officers stated that he found the gun stored in the bedroom and fired it while alone. The official ruling classified the death as suicide.

When Thomas Brennan returned home, he found his son lifeless in the room. Accounts in legal documents describe the gun near the body and a bible on the bed. At that point, events and timing become a central focus of later criticism.

Advocacy sites and some secondary reports state that Thomas phoned Denise Miscavige Gentile, a Scientologist and sister of church leader David Miscavige, before contacting emergency services. She and her husband later appeared as defendants in the wrongful death lawsuit.

Police logs show that the 911 call reached authorities later that night, after whoever had gathered at the apartment decided to involve first responders. When officers and paramedics arrived, Kyle had already died.

A crime scene that raised questions

The Clearwater Police Department treated the case as a suicide from an early stage. Critics, including Kyle’s mother, have focused on details of the scene that they view as inconsistent or poorly documented.

A family backed website that draws on depositions and internal records states that the revolver tested negative for identifiable fingerprints or ridge detail. The same site says officers recovered fourteen pieces of evidence from the apartment, all free of prints.

Those claims appear in legal briefs as well, where attorneys describe a weapon and bullet without usable prints. The filings argue that the absence of prints complicates any firm conclusion about how the gun moved and who handled it before or after the shot.

Family advocates also highlight a missing bullet. They state that investigators never recovered the projectile that caused the fatal injury, despite search efforts in the small bedroom. This point appears again and again in critical commentary on the case.

According to those same sources, police did not perform gunshot residue testing on Kyle’s hands or on his father’s. They also question documentation of blood patterns and the handling of ammunition boxes at the scene. These concerns feed alternative theories about what happened.

Authorities have stood by their conclusion. Clearwater police statements and later court summaries present the death as self inflicted, with no evidence strong enough to support homicide charges against Thomas Brennan or any Scientology related figure.

A lawsuit built around medication and influence

In 2009, Victoria Britton, acting for Kyle’s estate, filed a wrongful death lawsuit in federal court. The complaint named the Church of Scientology Flag Service Organization, Thomas Brennan, Denise Miscavige Gentile and her husband as defendants.

The suit argued that Scientology beliefs and advice played a role in Kyle’s vulnerability. It claimed that church representatives pushed to remove his Lexapro and that his father obeyed those instructions, despite warnings from Kyle’s psychiatrist about abrupt changes.

A psychiatrist’s opinion cited in the filings linked the sudden loss of medication, combined with stress in Clearwater, to a serious decline in Kyle’s mental state. The opinion described this shift as a significant factor in the events that led to his death.

Defendants denied responsibility. The church maintained that Kyle’s death resulted from personal troubles unrelated to Scientology practice, and that any advice about medication fell within religious expression. Thomas Brennan also rejected claims that he acted negligently toward his son.

In 2011, a federal judge granted summary judgment for the defendants, ruling that the evidence did not meet the standard for liability under Florida law. An appeals court later upheld that decision, and the case closed without a trial.

Legal outcomes settled the formal dispute, yet they did not resolve the questions that trouble Kyle’s family and outside observers. Blogs, interviews and advocacy projects continue to examine the record and argue that important aspects of the case remain unclear.

Clearwater, Scientology and a wider pattern of controversy

Kyle died in a city shaped strongly by Scientology’s presence. Since the 1970s, the organisation has treated Clearwater as its spiritual headquarters and has acquired a large number of downtown buildings and properties through church entities and member run companies.

This concentration has created recurring tension between Scientology and some residents, politicians and journalists. Supporters describe redevelopment and business projects. Critics perceive secrecy, insularity and an unusual level of control over a central urban district.

The church’s sharp opposition to psychiatry adds another layer. Scientology teachings frame psychiatric treatment as harmful. High profile campaigns highlight alleged abuses and promote spiritual counselling as a preferable alternative, which shapes how members respond to mental distress.

This stance has surfaced in other high profile cases. The death of Lisa McPherson in 1995, for instance, involved a Scientologist who left a hospital against medical advice after fellow members encouraged church based treatment instead of psychiatric care.

McPherson spent seventeen days under church supervision at the Fort Harrison Hotel in Clearwater before she died from a pulmonary embolism. A medical examiner initially labelled the death a case of negligent homicide, which led to criminal charges against a church corporation.

Prosecutors later dropped those charges after a change in the medical examiner’s findings, and the church settled a separate wrongful death suit with McPherson’s family. Scientology maintains that staff cared for her in good faith and rejects allegations of abuse.

Other deaths with Scientology in the background

In 2003, glass artist and Scientologist Elli Perkins died in Buffalo after her son Jeremy stabbed her repeatedly. He had schizophrenia, and reports describe efforts to treat him with vitamins and Scientology based methods instead of antipsychotic medication.

Jeremy later entered a psychiatric facility and received medication. In court proceedings and media coverage, his lawyers and outside commentators linked the lack of earlier psychiatric treatment to his progression toward violent psychosis. Scientology representatives criticised that framing.

Another case that attracts periodic attention involves Philip Gale, an exceptionally talented young computer programmer raised in Scientology. He died by suicide at MIT in 1998 after a period of depression and distance from the church.

Journalists and former acquaintances have discussed how leaving Scientology complicated his sense of identity, although official investigations into his death focused on mental health pressures common among high achieving students. Scientology authorities reject suggestions that church involvement caused his suicide.

More recently, a wrongful death suit filed in Florida over the 2022 suicide of Scientologist Whitney Mills alleges that church figures discouraged her from obtaining psychiatric care despite clear distress. The church again denies wrongdoing and frames the matter as a private tragedy.

These cases differ in circumstances, geography and individual histories. They do, however, share recurring themes: tension over psychiatric treatment, internal handling of crises, and later disputes about how much influence church teachings exerted over crucial decisions.

Kyle’s place in that landscape

For supporters of Scientology, the official ruling on Kyle Brennan’s death closes the question. They point to police findings, court judgments and the absence of criminal charges as evidence that a troubled young man took his own life in a sad, isolated act.

For his mother and for critics of Scientology, Kyle’s death sits beside cases like Lisa McPherson’s and Elli Perkins’s as part of a wider pattern that connects doctrinal hostility to psychiatry with avoidable risk and unresolved doubt.

Websites, longform blog series and interviews continue to revisit deposition excerpts and forensic notes from Clearwater. They highlight missing bullets, clean weapons and removed medication as pieces of a puzzle that feels incomplete.

Kyle’s own life appears in these accounts through school records, art, online posts and an obituary that describes a young man with creative interests and a close bond with his mother. That personal picture gives weight to ongoing efforts to scrutinise the record.

Official files still list his death as suicide in a Clearwater apartment in February 2007. The parallel archive built by his family and allies preserves a different emphasis, one that centres unfinished questions about influence, evidence handling and the choices made around his final days.