INTRODUCTION: A STUDY GOES OFF THE RAILS

Researchers at Stanford wanted to see if pretending to be guards and prisoners could change people’s behavior. They set up a fake jail.

They planned for two weeks of observation. Instead, they stopped after six days. The project took a scary turn, revealing how power can spin out of control.

Decades later, arguments still swirl. Some people see it as a lesson in human nature, while others call it flawed from the start.

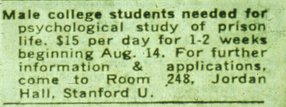

A NEWSPAPER AD: $15 A DAY

This experiment kicked off with a simple ad offering $15 daily. In today’s money, that’s around $116. It seemed easy: just pretend to be inmates or guards.

Seventy-five college men answered. The team weeded out folks with issues or records. They picked 24 who seemed stable and average.

Those 24 were split in half. One group played guards, the other played prisoners. A coin toss decided their fate, aiming to remove any bias.

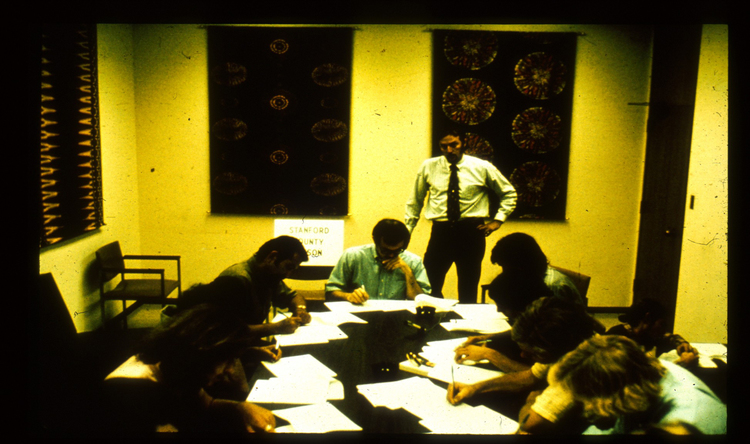

WHY THE NAVY FUNDED IT

The U.S. Navy and Marines had problems inside their own lockups. They wanted to know why guard-prisoner tensions ran so high.

Philip Zimbardo was curious about how environments might push people to act in extreme ways. The Navy saw a chance to learn.

This funding later stirred suspicions. Some critics wondered if the design was nudged by military goals, shaping how the study was run.

BASEMENT INTO A LOCKUP

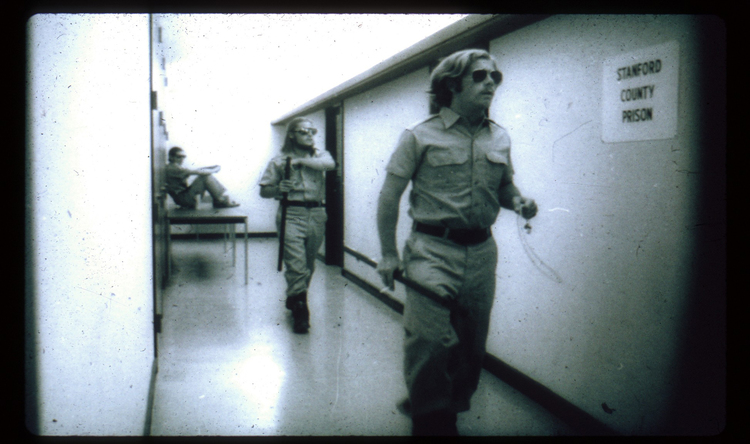

They transformed a cramped hallway in Stanford’s Jordan Hall into a makeshift prison. Temporary walls turned small rooms into cells for three prisoners each.

A narrow corridor served as the yard. There was even a little closet for solitary confinement. The guards got their own office across the hall.

Zimbardo and his team told the guards to keep order and prevent escapes. Physical violence was off-limits, but strict discipline was allowed.

DAY ONE: SURPRISE ARRESTS

On August 14, the local Palo Alto police arrested each student prisoner at home, without warning. Neighbors saw them handcuffed and read their rights.

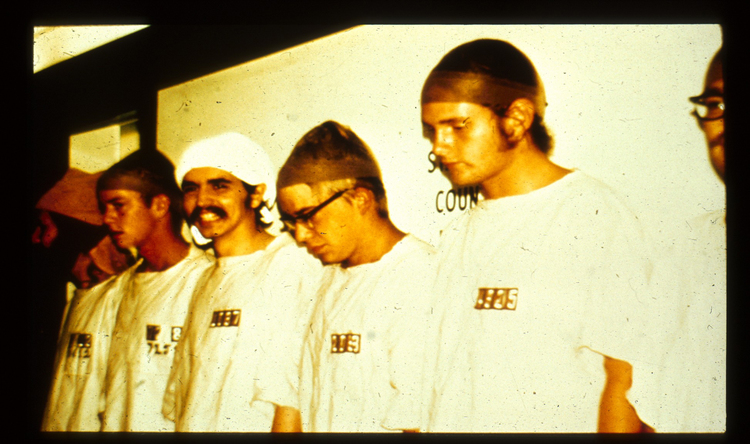

At the station, they were fingerprinted and photographed like real suspects. Then they were taken to the Stanford “jail,” stripped, and “deloused.”

They got ill-fitting smocks, no underwear, and stocking caps instead of normal clothes. They also wore ankle chains that rattled as a constant reminder.

A QUICK COSTUME CHANGE

The awkward smocks were meant to humiliate them. Each prisoner was identified by a number instead of a name. The goal: erase their sense of identity.

Guards, meanwhile, got khaki uniforms, batons, and mirrored sunglasses. These props, Zimbardo believed, would push them to act more forceful and less empathetic.

The plan seemed simple at first. But that first day hinted at looming tension, with prisoners uneasy and guards already eyeing control.

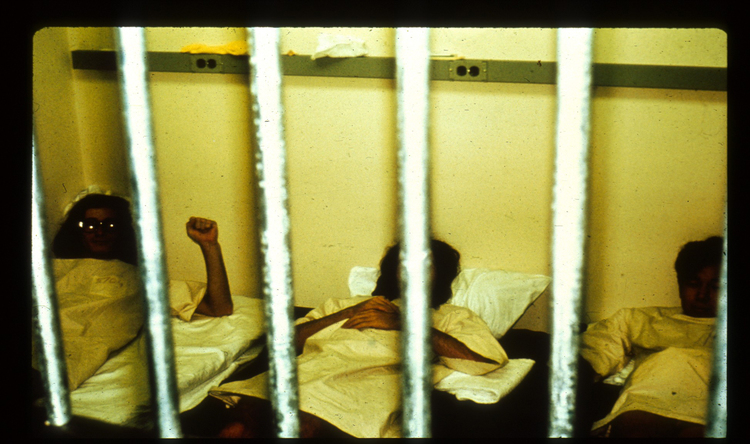

GUARD SHIFTS AND HOME BREAKS

Three guards worked each eight-hour shift. Afterward, they could head home, relax, and return later. Prisoners, however, were stuck there around the clock.

This huge freedom gap was meant to feel real. Guards lived normal lives outside, while prisoners faced stuffy cells and strict rules all day long.

Power differences soon became clear. Some guards felt emboldened by their uniforms and the knowledge that they could leave whenever they wanted.

DAY TWO: FIRST SIGNS OF REBELLION

Early on the second day, prisoners tore off their numbers and stocking caps. They barricaded their cells, yelling that they wouldn’t follow orders.

Guards responded with fire extinguishers. They burst in, took blankets, and stripped the cells. Suddenly, a simple experiment looked like a real-life prison riot.

Some prisoners were shoved into a cramped closet, nicknamed “the Hole.” Others were tempted with better meals if they behaved. Unity among inmates began to crumble.

PSYCHOLOGICAL WARFARE TAKES HOLD

Guards started pulling night shifts, forcing prisoners to do random tasks. They shouted orders and ridiculed those who didn’t comply. Tension filled the stale air.

A few prisoners caved and tried to avoid punishment. Others stayed angry or stubborn. Yet every night, the line between act and reality got blurry.

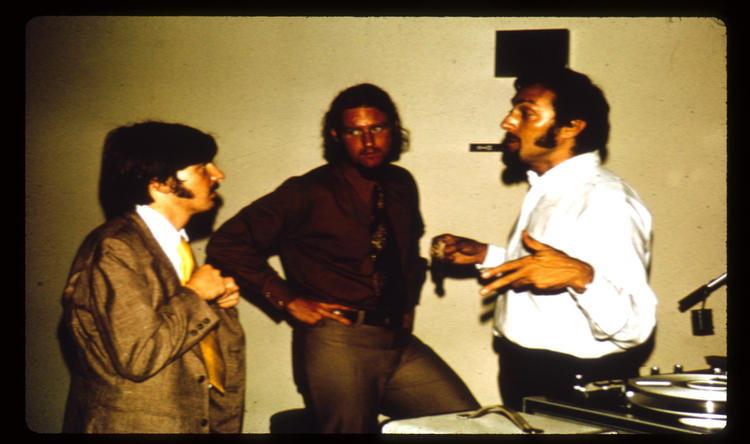

Zimbardo, acting as superintendent, often encouraged order. He didn’t see how far things were going. The role he played clouded his judgment about ethics.

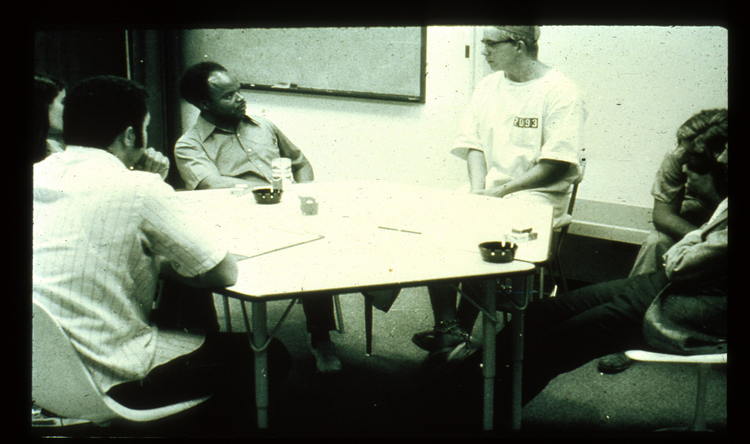

ENTER CHRISTINA MASLACH: THE VOICE OF REASON

Christina Maslach, fresh from graduate school, visited to see how things were going. She saw prisoners wearing paper bags over their heads and guards barking insults.

She was horrified. In her view, this was more than a game. She confronted Zimbardo, telling him it had become cruel and dangerous.

This moment was a wake-up call. Zimbardo realized he’d drifted from calm researcher into an overinvested prison boss, pushing boundaries far past normal.

CUTTING IT SHORT ON DAY SIX

The experiment ended after six days instead of fourteen. A few guards wanted to keep going, but it was clear the situation was unhealthy.

Several prisoners had shown severe stress, and some pleaded to leave. Guards were dishing out punishments more casually, as though it was just routine.

Zimbardo concluded the risks were too high. He pulled the plug, surprising those who believed the simulation should test their endurance even further.

HOW THE WORLD REACTED

News and photos of students humiliating classmates spread fast. The public was appalled but couldn’t look away, stunned by how roles flipped ordinary behavior.

Psychologists debated what it meant. Zimbardo said it showed how regular people could turn harsh in the wrong setting. Others were unconvinced by his claims.

Some called it a dramatic but flawed peek into human nature. The debate grew loud, fueling new ethical guidelines and intense scrutiny of research methods.

EARLY ARTICLES AND CONTROVERSY

Zimbardo published quick summaries in Naval Research Reviews and other outlets, creating buzz. Critics said he chased sensational headlines instead of careful peer review.

He insisted he followed the rules of his Navy grant. Later, major journals like American Psychologist did feature his work, adding more legitimacy in his eyes.

Still, questions lingered about whether the hype overshadowed genuine science. Some wondered if the urgent push for publicity diluted the study’s integrity.

A BIG ETHICAL FLASHPOINT

Psychology was already under fire for risky studies. Milgram’s shock experiments worried many people, and the CIA had its own shady research programs.

The Stanford Prison Experiment added fuel to this ethical storm. It showed how quickly participants could suffer mental harm if oversight was weak.

New rules emerged. Scientists had to provide clearer justifications, stronger consent forms, and better safety checks. The days of extreme stress tests became numbered.

DID PARTICIPANTS SENSE THE SCRIPT?

Some skeptics argue that the guards merely followed hints from Zimbardo. They say the study encouraged them to be rough, almost like they were in a play.

Zimbardo told the guards to prevent escapes and maintain control. He also stood nearby, making it seem he approved of stern approaches.

Critics think it became role-playing rather than a genuine psychological shift. Handing young men batons and telling them they’re guards might naturally spark tough behavior.

WHO VOLUNTEERS FOR PRISON RESEARCH?

Years later, researchers Carnahan and McFarland suggested the ad itself attracted certain personalities. People drawn to a “prison life” study might lean more authoritarian.

This means the experiment wasn’t random. Participants could already be prone to dominance. That weakens the idea that anyone could become abusive under those conditions.

Zimbardo counters that all were prescreened, but some doubt that process. They say the ad’s wording tilted the balance before the study ever began.

FRAUD CLAIMS AND RESEARCHER INFLUENCE

Another wave of criticism arrived when some historians argued that guards were guided to act tough. They pointed to taped conversations and transcripts.

In these records, at least one guard was told to play the “heavy” for stronger results. That implies the brutality wasn’t entirely spontaneous.

Zimbardo insists he never forced them. But the line between suggestion and instruction can blur in a setting where the boss is watching closely.

THE MOST NOTORIOUS GUARD: DAVID ESHELMAN

David Eshelman famously wore mirrored sunglasses, invented twisted routines, and drew inspiration from the movie Cool Hand Luke. He later admitted he was “playing a role.”

Some took this to mean the experiment was fake. If he was just imitating a sadistic warden, how real were the overall conclusions?

Zimbardo, however, noted Eshelman wasn’t alone in harsh behavior. Other guards also ramped up punishments, showing that control can build momentum among a group.

THE BBC PRISON STUDY: A CONTRAST

In 2002, psychologists Reicher and Haslam tried a similar project with the BBC. This time, they had strict ethics, constant supervision, and no single authority figure.

Their results were different. Prisoners united more, guards lost control, and cruelty wasn’t as widespread. Cameras were also filming, which may have changed behavior.

Fans of Zimbardo’s work say this wasn’t a pure redo. Critics believe it proves the dark spiral at Stanford was not inevitable but context-driven.

THE CONSULTANT’S TAKE: CARLO PRESCOTT

Carlo Prescott, once imprisoned at San Quentin, advised Zimbardo. Later, he claimed many humiliations came straight from his real prison experiences. They weren’t spontaneous guard ideas.

Zimbardo doubted Prescott wrote the critique himself. But this revelation made people doubt the “natural” unfolding of events. Maybe it was staged more than people realized.

If guards were handed these tactics in advance, it complicates any argument that the cruelty was purely an organic response to the basement environment.

AN ETHICAL SHIFT IN RESEARCH

After the Stanford Prison Experiment, many colleges strengthened their oversight. IRBs became stricter about risk and made researchers justify potential harms in careful detail.

Milgram’s work had already stirred debates about the ethics of deception and mental stress. The Stanford fiasco hit at the perfect moment to amplify concerns.

Researchers soon realized that pushing volunteers to extreme stress levels was no longer acceptable. The days of freewheeling psychological drama in labs were mostly done.

SCATTERED ARCHIVES AND NEW EVIDENCE

Over the years, audio clips and notes have surfaced online. In one recording, a warden nudges a guard to be tougher, hinting at the outcome researchers wanted.

Skeptics argue these tapes confirm the study was manipulated. Zimbardo’s supporters respond that these nudges were minor and the guards still had free will.

Documentaries and dramatized films further blur lines. They often highlight the most shocking parts, leaving out the quiet hours or the more nuanced details.

COMPARISONS TO REAL PRISONS

Zimbardo has compared his findings to Abu Ghraib, the infamous Iraqi prison scandal. He says the same psychological factors can push normal people toward cruel acts.

Some experts say that’s too simplistic. Real prisons involve complex social systems, fear, and tension that an undergraduate role-play can’t fully capture.

Still, the idea lingers that authority, once unchecked, can spark abusive behavior. It’s a theme that resonates far beyond one basement in Stanford.