Eight people walked into a sealed glass world in the Arizona desert on September 26, 1991, carrying the weight of a promise that sounded almost impossible. Live inside a miniature Earth. Grow your own food. Recycle your own air and water. Stay two years.

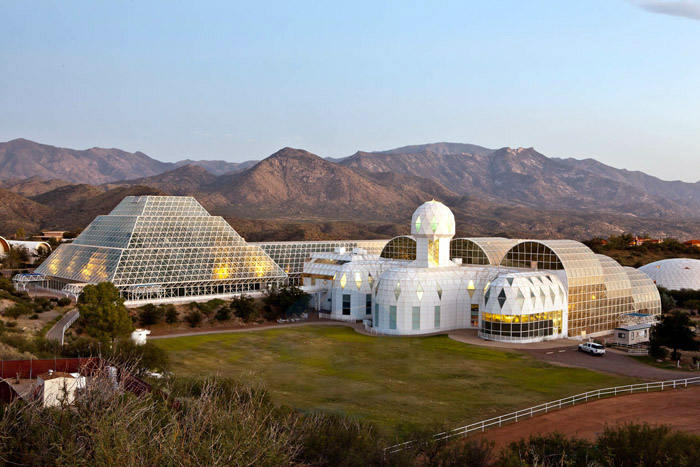

Biosphere 2 still sits near Oracle, Arizona, at the base of the Santa Catalina Mountains, about 50 minutes north of Tucson, at roughly 4,000 feet above sea level. Today it’s an Earth system science research facility owned by the University of Arizona, open to research, outreach, and visitors.

Calling it “Biosphere 2” was the point, not a branding trick. Earth was Biosphere 1. This structure aimed to become a second, fully self-sufficient biosphere, at least in theory, with humans included as part of the living system rather than outside observers.

Under the glass, designers built seven biome areas: a rainforest, an ocean with a coral reef, mangrove wetlands, a savannah grassland, a fog desert, plus two human-made biomes, an agricultural system and a human habitat with living quarters, labs, and workshops. Sizes were carefully defined, down to square meters and square feet.

Below ground, an extensive technical infrastructure carried heating and cooling water through independent piping systems. Sunlight powered biological work through passive solar input, while an onsite natural gas power plant supplied electrical power into the facility, tying biology to machinery from the start.

In popular memory, Biosphere 2 often gets reduced to a punchline or a cautionary headline. A later documentary brought it back into conversation, and some crew members still argue the baseline achievement was simple: the same number of people walked out as walked in.

Biosphere 2’s official story, though, is bigger than a single retelling. Construction ran between 1987 and 1991, after the project was launched in 1984 by Ed Bass and John P. Allen. Bass funded it with $150 million until 1991, backing an idea that mixed engineering ambition with ecological faith.

Bass and Allen had met in the 1970s at Synergia Ranch, a counterculture community associated with Allen and shaped by Buckminster Fuller’s “Spaceship Earth” concept. Several other former members of Synergia Ranch later joined the Biosphere 2 effort, carrying that shared history into a public science project.

Space Biosphere Ventures, a joint venture, carried out construction between 1987 and 1991. Wikipedia lists principal officers as John P. Allen, Margaret Augustine, Marie Harding, Abigail Alling, Mark Nelson, William F. Dempster, and Norberto Alvarez-Romo, reflecting how tightly the enterprise blended management and mission.

A separate timeline of the property predates the dome itself. The University of Arizona notes the land was once part of the Samaniego CDO Ranch in the 1800s and later functioned as a conference center in the 1960s and 1970s, first for Motorola and then for the university, before Space Biospheres Ventures bought the property in 1984.

Engineering had to solve a blunt challenge: keep air exchange so low that subtle changes could actually be measured, and keep the structure intact through daily expansion and contraction of air. Designers used steel tubing, high-performance glass, and steel frames, built to specification by Pearce Structures, led by Peter Jon Pearce.

Airtight sealing mattered enough to become a defining feature. Patented methods developed by Pearce and William Dempster achieved a leak rate of less than 10% per year, tight enough that a slow oxygen decline of less than one-quarter percent per month could be detected instead of disappearing into ordinary leakage.

Heat created pressure swings that a normal building could relieve by cracking a window. Biosphere 2 couldn’t. Two “lungs,” or variable-volume structures, used large diaphragms housed in domes to absorb the daily expansion and contraction of internal air without forcing pressure against glass beyond design limits.

Temperature control needed its own backbone. Cooling was the largest energy demand, with heating also required in winter, so closed-loop pipes and air handlers became key. An on-site energy center provided electricity and heated and cooled water using natural gas, backup generators, ammonia chillers, and water cooling towers.

University of Arizona material adds more physical “fast facts”: about 7.2 million cubic feet under sealed glass and about 6,500 windows, with the structure reaching 91 feet at its highest point. UA also describes a 500-ton welded stainless steel liner sealing the enclosure from the earth below.

Inside, the work was meant to be continuous and measurable. The design wasn’t only about pretty biomes; it was a laboratory meant to study interactions among humans, farming, technology, and ecological processes, framed as a path toward knowledge useful for space colonization and as an experimental facility for manipulating a mini biospheric system.

Biosphere 2 was used twice as a closed-system experiment. The first closure ran from 1991 to 1993. The second ran from March to September 1994. Both runs collided with unexpected ecological behavior, human conflict, and outside politics, even as staff and participants argued that surprises were the point.

The first mission’s crew was named and public: Roy Walford, Jane Poynter, Taber MacCallum, Mark Nelson, Sally Silverstone, Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, and Linda Leigh. They entered September 26, 1991, and emerged September 26, 1993, finishing the planned two-year closure.

Agriculture filled their days because food wasn’t a prop. The agricultural system produced 83% of the total diet, including bananas, papayas, sweet potatoes, beets, peanuts, lablab and cowpea beans, rice, and wheat. Hunger persisted, especially during the first year, even as productivity looked extraordinary.

Calculations cited on Wikipedia described the Biosphere 2 farm as among the highest producing in the world, exceeding by more than five times the output of the most efficient agrarian communities in Indonesia, southern China, and Bangladesh. High yield didn’t cancel daily hunger. It sharpened it.

Roy Walford’s medical lens shaped the crew’s diet and the data recorded. Participants ate a low-calorie, nutrient-dense regimen tied to Walford’s research on lifespan extension. Medical markers reportedly stayed excellent, with improvements in cholesterol, blood pressure, and immune system indicators across the two years.

Weight loss became part of the experiment’s fingerprint. Wikipedia reports the biospherians lost an average of 16% of their pre-entry body weight before stabilizing, then regained some in the second year. Later studies cited there suggest metabolism became more efficient at extracting nutrients as an adaptation to sustained restriction.

Food production wasn’t only plants in beds. Domesticated animals in the agricultural area included four African pygmy goat does and one billy, 35 hens and three roosters, two sows and one boar of Ossabaw dwarf pigs, plus tilapia fish grown in a rice and azolla pond system with ancient roots in China.

At the same time, one later account emphasized just how unromantic the daily menu could feel. Linda Leigh recalled craving more calories, watching slow-growing crops fail expectations, and seeing coffee bushes that took about a fortnight to produce enough for a single cup, while meals leaned heavily on beets and sweet potatoes.

A strategy called “species-packing” tried to guard against ecological collapse by overloading biodiversity at the start, assuming losses while hoping food webs would still function. Even so, the fog desert drifted toward a chaparral character as condensation accumulated, and savannah biomass was cut and stored as part of carbon dioxide management.

Rainforest pioneer species grew fast, yet trees in the rainforest and savannah developed weakness and etiolation linked to lack of stress wood. In ordinary forests, wind prompts structural strengthening; inside a sealed world, the absence of that pressure became a physical signature in trunks and branches.

Ocean life demanded active human correction. Corals reproduced, but the crew maintained system health by hand-harvesting algae, manipulating calcium carbonate and pH to prevent increasing acidity, and installing an improved protein skimmer to supplement the algae turf scrubber originally installed for nutrient control.

Mangroves grew quickly, though with less understory than typical wetlands, possibly tied to reduced light levels. Even so, the mangrove area was judged a successful analogue to Florida’s Everglades region, where mangroves and marsh plants used in the biome had been collected.

Biosphere 2’s small size and dense concentration of organic materials accelerated the tempo of ecological change. Wikipedia describes larger fluctuations and faster biogeochemical cycles than on Earth. Most introduced vertebrate species and virtually all pollinating insects died, even as many plants and animals still reproduced.

Pests flourished in the gaps left behind. Cockroaches surged. A globally invasive tramp ant, Paratrechina longicornis, came to dominate other ant species. Yet planned ecological succession in the rainforest and strategies to protect it from harsh sunlight and salt aerosols worked well enough that surprising biodiversity persisted.

Early development inside the dome was likened to island ecology, a closed space where colonization, extinction, and dominance can race forward. That framing mattered because the project’s premise was not only survival, but observation of a living web under pressure, compressed into a measurable chamber.

Ecology wasn’t the only system under stress. Human behavior became part of the closed loop. Wikipedia links this to “confined environment psychology,” drawing on studies of Antarctic research crews overwintering in isolation, where faction formation and emotional amplification are recurring patterns rather than exceptions.

Jane Poynter later described faction-splitting as expected in such environments, and Wikipedia says the group divided before the mission was halfway over. People who once felt close became enemies and barely spoke. Roy Walford, blunt as ever, later admitted dislike alongside cooperation: “we ran the damn thing.”

Those factions weren’t only personal. Wikipedia ties them to a rift between joint venture partners over what kind of science the project should prioritize. One camp, including Poynter, pushed for increasing research even if it reduced closure purity, while the other backed management and overall mission objectives.

Outside credibility cracked in public view. On February 14, part of the Scientific Advisory Committee resigned, and Time magazine described a bruised “veneer of credibility” amid allegations about tamper-prone data and smuggled supplies, calling the project increasingly like a $150 million stunt rather than science.

The Scientific Advisory Committee was dissolved after drifting beyond its mandate and advocating management changes. Some members stayed on as consultants. Recommendations still shaped operations: Jack Corliss became Director of Research, and import-export of scientific samples and equipment through airlocks was allowed to expand research and reduce crew labor.

Wikipedia says Walford and Alling spearheaded development of a formal research program that included about 64 projects. That detail cuts against the idea of a sealed reality show, even as the public spectacle stayed loud, visible, and sometimes cruel, with outsiders watching the inside world as entertainment.

Reports about interpersonal strain sometimes turned into melodrama, yet Wikipedia notes psychological examinations found no depression among the biospherians. Results suggested an explorer or adventurer profile, with women and men scoring similarly to astronauts, even when some participants privately believed they were depressed.

Ecological surprises piled up alongside human strain. Unanticipated condensation made the “desert” too wet. Greenhouse ants and cockroaches exploded. Morning glories overran the rainforest area, blocking other plants. Less sunlight entered than expected, roughly 40% to 50% of outside light, forcing constant adaptive management.

Crew interventions became a kind of ecological role. Biospherians controlled invasive plants to preserve biodiversity, functioning as “keystone predators” in a system that otherwise lacked large predators. Even construction choices turned into science problems, including the difficulty of manipulating bodies of water to generate waves and tidal changes.

Public controversy sharpened when an injured member left and returned, carrying new material inside. The team said only plastic bags came in, while critics suspected food and supplies. A later summary described Jane Poynter leaving for medical attention and re-entering with a duffel bag, while disputing that it contained vital supplies.

Air became the experiment’s sharpest edge. Oxygen began at 20.9% and fell steadily. After 16 months it was down to 14.5%, equivalent to oxygen availability at about 4,080 meters. Some biospherians developed symptoms such as sleep apnea and fatigue, prompting injections of oxygen in January and August 1993.

Wikipedia also links oxygen decline to biomedical insight. Minimal response of the crew suggested changes in air pressure, not only oxygen percentage, trigger human adaptation responses. In that framing, the experiment accidentally generated biomedical observations alongside ecological data, even while critics questioned whether intervention broke the mission.

Carbon dioxide behavior complicated everything. Daily fluctuation was typically around 600 ppm, with strong drawdown during daylight photosynthesis and comparable rise at night during respiration. Wintertime CO2 could reach 4,000–4,500 ppm, while summer levels hovered near 1,000 ppm, forcing constant management decisions.

Crew members tried ecological levers first: turning irrigation on and off in desert and savannah zones, cutting and storing biomass to sequester carbon, planting fast-growing species to increase photosynthesis. When those measures failed to sustain human life safely, they occasionally turned on a CO2 scrubber.

That scrubber became a media flashpoint. Investigative reporting in The Village Voice in November 1991 alleged the device had been secretly installed, framing it as betrayal of the project’s advertised goal of natural recycling. Others argued the device was not secret and simply another technical system augmenting ecological processes.

A carbon precipitator added another layer. Wikipedia notes it could reverse chemical reactions, releasing stored carbon dioxide in later years if additional carbon was needed. Soil selection also mattered: soils were chosen with enough carbon to support a calculated 20 short tons of plant mass increase from infancy to maturity.

Microbes wrote their own script. The release rate of soil carbon as carbon dioxide through microbial respiration was an unknown the experiment aimed to reveal. Later research cited on Wikipedia says farm soils reached a more stable carbon-to-nitrogen ratio by 1998, lowering the rate of CO2 release compared with earlier years.

A deeper mystery sat under the numbers. Respiration ran faster than photosynthesis, likely influenced by low light penetration and the rapid increase of plant biomass from a small start, which contributed to slow oxygen decline. Yet carbon dioxide did not rise as expected, hiding the real sink at work.

Isotopic analysis later pointed at concrete. Jeff Severinghaus and Wallace Broecker of Columbia University’s Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory concluded carbon dioxide was reacting with exposed concrete to form calcium carbonate through carbonatation, sequestering both carbon and oxygen and masking the missing gas in plain sight.

By September 26, 1993, the first crew emerged, and the argument over what the project “proved” went public. One view cast it as a landmark ambition; another dismissed it as New Age theater. Wikipedia records both extremes, from moonshot praise to “drivel masquerading as science.”

Some criticism targeted credentials and culture, not data. In 1991, Marc Cooper described the project leadership as recycled theater performers evolving from an authoritarian personality cult, pointing to Synergia Ranch in New Mexico, where many biospherians practiced theater under John Allen’s leadership and developed early ideas.

Biosphere 2’s builders pushed back with their own resumes. Wikipedia lists mainstream credentials for Allen and Walford and later academic work by crew members: Allen’s engineering degree from the Colorado School of Mines and an MBA from Harvard Business School, Walford’s University of Chicago medical degree and long UCLA pathology career, plus later PhDs and research careers among crew.

Mark Nelson’s later PhD work is linked to ecological engineering, including constructed wetlands used for sewage treatment and recycling in Biosphere 2, alongside coral reef protection work tied to the Yucatán coast. Linda Leigh’s later PhD dissertation focused on biodiversity and the Biosphere 2 rainforest, working with H.T. Odum.

Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, and Sally Silverstone helped start the Biosphere Foundation, pursuing coral reef and marine conservation and sustainable agriculture. Jane Poynter and Taber MacCallum co-founded Paragon Space Development Corporation, which has worked on life-support systems and space-related biological milestones described on Wikipedia.

Even internal consultants wrestled with the project’s culture. Ghillean Prance, then director at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, designed the rainforest biome. In a 1983 interview he described feeling ill-used and suspected a secret agenda, later moderating his view while still calling the group “visionaries” and “somewhat cultlike.”

Poynter’s memoir directly rebuts the notion that lack of degrees among some managers invalidated results, arguing credibility should hinge on quality of work and pointing to later achievements in space-linked engineering. Wikipedia includes her pushback as part of the broader fight over legitimacy rather than a simple scientific scoreboard.

In August 1992, the Biosphere 2 Science Advisory Committee, chaired by Tom Lovejoy of the Smithsonian Institution, framed the facility as “vision and courage,” describing its scale as unique and pointing to unexpected findings, notably oxygen decline. It argued Biosphere 2 could contribute to biogeochemical cycling and restoration ecology.

After the first mission, improvements targeted known weak points, including sealing concrete to prevent carbon dioxide uptake. A second mission began on March 6, 1994, announced as a ten-month run. Crew members were Norberto Alvarez-Romo, John Druitt, Matt Finn, Pascale Maslin, Charlotte Godfrey, Rodrigo Romo, and Tilak Mahato.

Wikipedia reports the second crew achieved complete sufficiency in food production and did not need oxygen injection before the experiment ended early. In another timeline of the story, that success rarely gets the spotlight because politics and conflict crashed down almost immediately from outside the glass.

On April 1, 1994, a severe dispute within the management team led to federal marshals serving a restraining order and ousting on-site management. Ed Bass hired Steve Bannon, then managing an investment banking team at Bannon & Co in Beverly Hills, to run Space Biospheres Ventures as the project entered receivership.

Wikipedia lists the dispute’s stated causes as mismanagement producing terrible publicity, financial mismanagement, and lack of research. It also records allegations of gross financial mismanagement, including a claimed $25 million loss in fiscal year 1992. Two former crew members flew back to Arizona, protested the hire, and broke in to warn the crew.

That conflict escalated into a dramatic early-morning incident. At 3 a.m. on April 5, 1994, Wikipedia says Abigail Alling and Mark Van Thillo allegedly vandalized the project from outside, opening airlock and emergency exits for about 15 minutes and breaking five panes of glass, exchanging about 10% of the air with outside.

Alling later told the Chicago Tribune she considered the Biosphere in an emergency state and said it was not sabotage. Systems analyst Donella Meadows is cited as receiving communication from Alling arguing it was an ethical duty to offer those inside a choice, because they did not know what the crew had been told about the takeover.

Meadows’s quoted passage paints the takeover in detail: limousines arriving around 10 a.m. April 1 with investment bankers hired by Bass, police officers, changed locks, changed communications, and blocked access to data. Alling’s letter emphasized the sudden managers “knew nothing technically or scientifically,” deepening the inside-outside rupture.

Four days after the break-in episode, captain Norberto Alvarez-Romo, by then married to chief executive Margaret Augustine, left for a “family emergency” after Augustine’s suspension. Wikipedia says Bernd Zabel replaced him, and two months later Matt Smith replaced Matt Finn, reflecting a mission already reshaped by crisis.

Space Biospheres Ventures was dissolved on June 1, 1994, leaving scientific and business management to an interim turnaround team contracted by Decisions Investment Co. Mission 2 ended prematurely on September 6, 1994. Wikipedia says no further total system science emerged as the facility shifted away from closed ecological research.

Bannon’s time at Biosphere 2 left a legal wake. Wikipedia says he left after two years, but his departure was marked by an “abuse of process” civil lawsuit filed against Space Biosphere Ventures by former crew members who had broken in. The court ruled for plaintiffs and ordered SBV to pay $600,000.

At a 1996 trial, Wikipedia reports Bannon testified he called Abigail Alling a “self-centered, deluded young woman” and a “bimbo,” and said he promised to shove a five-page safety complaint “down her throat.” He attributed the conflict to “hard feelings and broken dreams,” a phrase that fits the wreckage.

By December 1995, Biosphere 2’s owners transferred management to Columbia University in New York City. Columbia ran it as a research site and campus until 2003, shifting the facility’s identity from a sealed-world survivability drama into a more conventional research installation, then returning management to owners afterward.

Columbia also changed the building’s operating logic. In 1996, it converted the virtually airtight, materially closed structure into a “flow-through” system and halted closed system research. Scientists manipulated carbon dioxide levels for global warming research by injecting CO2 and venting as needed. Students often spent semesters onsite.

Research during Columbia’s tenure used the controllable ocean mesocosm to test atmospheric change effects on coral reefs. Wikipedia says studies demonstrated severe impacts from elevated CO2 and acidification, and quotes Frank Press, former National Academy of Sciences president, calling it the “first unequivocal experimental confirmation” of human impact on the planet.

Terrestrial biomes also yielded sobering patterns. Wikipedia describes a saturation point reached under elevated CO2 beyond which systems could not uptake more. Authors noted striking whole-system differences between rainforest and desert biomes and argued this contrast shows why large-scale experiments matter for complex global change questions.

While Columbia pursued new research modes, a larger archive of Biosphere 2 science sat in limbo. Wikipedia says a 1999 special issue of Ecological Engineering, “Biosphere 2: Research Past and Present,” edited by Marino and Howard T. Odum, became the most comprehensive assembled set of collected papers and findings.

Those papers ranged from calibrated models of system metabolism, hydrologic balance, heat and humidity to studies of rainforest, mangrove, ocean, and agronomic development in a CO2-rich environment. Yet Wikipedia also notes much original data has never been analyzed and is unavailable or lost, possibly due to politics and in-fighting.

Science historian Rebecca Redier argued the project’s outsiders status fueled media scrutiny and misunderstanding, and that the scrutiny eased once Columbia assumed management because the institution was seen as “proper” science. Biosphere 2’s story often turns on who gets believed, not only what data says.

In January 2005, Decisions Investments Corporation, owner of Biosphere 2, announced the 1,600-acre campus was for sale. They preferred a research future but did not exclude buyers with different intentions, including large universities, churches, resorts, and spas, which hinted at how close demolition fears could get.

In June 2007, the site sold for $50 million to CDO Ranching & Development, L.P. Plans mentioned 1,500 houses and a resort hotel, while also stating the main structure would remain available for research and educational use, a compromise that left the dome standing while the surrounding land changed direction.

On June 26, 2007, the University of Arizona announced it would take over research at Biosphere 2, ending fears the structure would be demolished. Officials said private gifts and grants could cover research and operations for three years, with the possibility of extending support for ten years, which later happened.

One gift in 2009 added 470 photovoltaic solar panels. In June 2011, the university announced it would assume full ownership effective July 1. CDO Ranching & Development donated land and buildings, and the Philecology Foundation, founded by Ed Bass, pledged $20 million in 2011 for science and operations.

In 2017, Ed Bass donated another $30 million to the University of Arizona to support Biosphere 2, endowing two academic positions and creating the “Philecology Biospheric Research Endowment Fund.” Public engagement remained part of the model, with Wikipedia noting science camps and reporting an average of 100,000 visitors per year in 2011.

University of Arizona material gives a broader public-facing scale: a 40-acre campus, extensive added buildings for offices, classrooms, labs, and housing, and visitor totals described as over 3,000,000 since 1991, including more than 500,000 K–12 student visitors. Those numbers reflect how the dome became a science site and a tourist site at once.

Research since the Arizona takeover widened beyond the original space-colony framing into Earth-focused questions. Wikipedia lists a portfolio of smaller projects alongside several large-scale installations, using the facility as a controlled environment for climate, soil, water-cycle, and human-technology experiments that are hard to run in the open world.

The Landscape Evolution Observatory, or LEO, is one of the marquee examples. It uses 1,800 sensors to track how millions of pounds of abiotic volcanic rock slowly develop into soil capable of supporting microbial and vascular plant life. Building it required constructing three steel-framed “hillsides” inside existing domes, constrained by access limits.

Another project, the Lunar Greenhouse, serves as a second prototype linked to the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center. Its aim is to understand how to grow vegetables on the Moon or Mars by developing a bioregenerative life support system that recycles and purifies water through plant transpiration, echoing the original survivability ambition in a tighter frame.

Plans for vertical farming push that logic further. Wikipedia describes a project to be built in the west lung with Civic Farms, using LED lamps tuned to specific wavelengths to increase water efficiency, produce zero farm runoff, avoid pests and pesticides, and remove dependence on external weather conditions, essentially turning controlled agriculture into an engineered loop.

Another repurposed element is the Space Analog for the Moon and Mars, a sealed research habitat adapted from Biosphere 2’s Test Module. Wikipedia frames it as a place to study human-in-the-loop technology, including bioregenerative life support systems, using real confinement conditions without repeating a full two-year closure spectacle.

Biosphere 2’s cultural shadow remains strange and persistent. Wikipedia lists the 1996 comedy film Bio-Dome as based on it, the 2016 novel The Terranauts as inspired by it, and the 2020 documentary Spaceship Earth as a direct return to the original experiment. Few research facilities have such a split legacy between science and satire.

Even the basic fact of public access is part of the identity. Wikipedia notes Biosphere 2 is one of only two enclosed artificial ecosystems in the Americas open to the public, alongside the Montreal Biodome. That detail captures a lingering tension: a living laboratory that also functions as a spectacle people walk through.

In the end, Biosphere 2’s story is not one clean verdict. Wikipedia preserves the contradictions: oxygen injections that sparked criticism, ecological die-offs paired with thriving pests, an internal split matched by external power struggles, a second mission that reached food sufficiency but collapsed under management conflict, and later decades of research under new institutions.

That contradiction might be the most faithful mirror of what the project tried to model. A system can be engineered to hold air and water, and still be reshaped by microbes, chemistry, politics, money, and human behavior. Biosphere 2 tried to compress Earth’s complexity into glass, and got complexity anyway.