The population at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the late 1960s, mostly revolved around the folks at Harvard University.

The environment there was one of academic order, and the most violent crimes in the community were usually related to petty larceny or late night disputes between students.

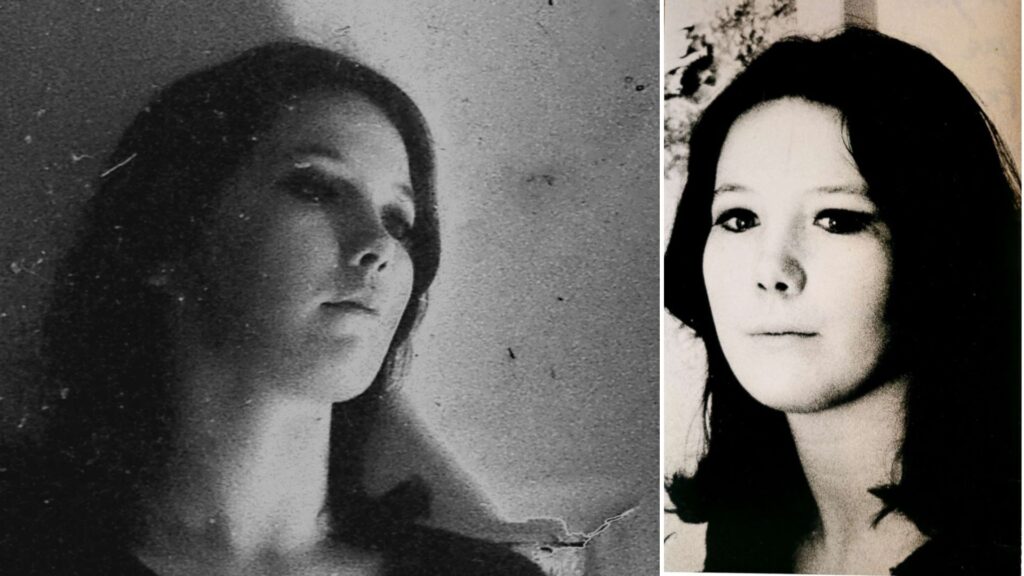

Hardened homicide in this area was a rare occurrence. It was in this nondescript setting that Jane Britton, a twenty three year old graduate student in anthropology, was murdered in her apartment near Harvard Square.

Britton, the daughter of an administrator at Radcliffe College, had spent her youth in Needham, Massachusetts. She had graduated magna cum laude from Radcliffe College and had gained admittance into Harvard’s graduate program in anthropology, where she was considered to be disciplined and academically driven.

In 1968, she had joined an archaeological expedition in Iran, where she had helped to locate certain ancient ruins. Among her peers and professors, she was considered to be disciplined, able, and dedicated to a career in academia. She lived alone in a small apartment near Harvard Square.

For Britton, the majority of January 7th, 1969, had passed on in a remarkably uneventful way. She had spent the early evening with friends at the Acropolis restaurant in Cambridg, and after dinner, she met her boyfriend, James Humphries.

The two went ice skating on the Cambridge Common. At around 10:30 p.m., they returned to her fourth floor apartment near Harvard Square, where her boyfriend had remained for approximately an hour before leaving.

Some time later, Britton emerged again, walking to a neighbouring apartment to fetch her cat, which she had left there earlier. This was the last known activity she undertook, according to investigators. Later evidence indicated that she was murdered shortly after returning to her apartment.

By the next morning, Britton had not shown up for certain academic assessments, which were later termed by her boyfriend to have been “critical” to her academics.

When unanswered calls continued, her boyfriend and a group of residents from a neighbouring apartment forced their way into her apartment.

There, they found Britton with her face down upon her bed, with a rug and fur coat covering her upper body, a fact that was later confirmed by the district attorney and entered into official case records.

According to Cambridge police reports, and recent reports released by the DA’s office, most of the blood in the apartment was found in the bed.

The autopsy reports revealed that Britton had been sexually assaulted (a fact that police did not release to the public for several months), and then struck multiple times in the head with a weapon that ‘had a point’, according to detectives. It was speculated to have been a hatchet or cleaver.

Later, the Lead Detective Leo Davenport noted that the murder might have been carried out using a stone with a pointed end, a souvenir that Britton had brought back from her Iranian dig, and was missing from the apartment.

It appeared to detectives that Britton had probably been attacked while she was asleep, and the blows seemed forceful, repetitive, concentrated at the skull, and delivered at a close range.

Further toxicology reports confirmed that the alcohol that she had consumed earlier in the evening had not entered her bloodstream yet, which confirmed that the attack had occurred shortly after her return back home.

The killing had neither been sudden, nor accidental; involving sustained physical violence in a confined space, and ending only when the injuries became fatal.

It was postulated by some that the killer might have been under the influence of hallucinogens when the act was perpetrated, something that was popular with the members of the counterculture at that point.

Two windows were found open in the apartment, including one in the kitchen, which Humphries would later notice, and another in Britton’s bedroom.

Residents later told police that the building’s heating system was so erratic that many tenants slept with their windows open even in winter, leaving investigators uncertain whether the windows were incidental or whether the assailant had entered or exited through them.

The crime scene, however, had an unusual element to it. Britton’s body had been marked with red ochre powder, a substance historically associated with ancient Persian burial rituals.

Its presence initially prompted speculation that the person responsible was someone familiar with anthropology, and also knew Britton, possibly as a classmate or a faculty member. This theory, however, was later abandoned when the police discovered that Britton was also a painter.

Prosecutors noted that ochre was a common pigment used in oil paints, and the police surmised that the powder was probably already in the apartment and had been disturbed upon the perpetrator’s entry. This piece of evidence was later downgraded to a circumstantial detail.

The violence of the crime, however, was in stark contrast to the surroundings. There had been no sign of break in, and nothing of value had been taken. The violence had seemed to be deliberate and prolonged, but not necessarily spontaneous, and the police quickly surmised that Britton probably knew her attacker or had let them in willingly.

The crime immediately made headlines in the local and national press, partly due to the victim’s academic achievements and partly due to the fact that it seemed to suggest that a targeted, intimate murder had occurred within one of the most close knit intellectual communities in the country.

From the outset, the case challenged assumptions about safety within Cambridge’s academic core.

It raised questions not only about who had killed Jane Britton, but about how a targeted, intimate act of violence could occur within one of the country’s most closely regulated intellectual environments and remain unresolved for decades.

At various points, the murder has been variously associated in popular accounts with Albert DeSalvo, known as the Boston Strangler, who had confessed to similar crimes, although the police questioned whether he was indeed responsible for all the murders he had claimed.

In the years that followed, the lack of a known suspect led to speculation about the crime within the academic community, and rumors began to circulate that Britton had been involved in a personal relationship with a member of the faculty, and that a professor may have been responsible for her death.

Such rumors were never substantiated, but they persisted in part because it was assumed that the crime must have originated within her immediate academic community.

When DNA tests finally became available to investigators in the 1980s, the well preserved evidence from the murder was tested for DNA samples. The semen left by the killer did not match the profiles of any known offenders of the time, and a 2006 retest did not prove fruitful either.

It would take almost five decades for the crime to finally be solved.

During this time, Britton’s parents had already passed away, the media attention for the case waned, and the case had become a footnote in history, occasionally brought up in passing anniversaries or academic circles.

Friends and remaining family members were left to wonder if the perpetrator would ever be caught, or if Jane Britton’s death would forever be an unsolved mystery in the annals of both Cambridge and Harvard University.

The case would pick up again in 2017, when the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office began to receive several requests for the release of Britton’s case file to the public.

As part of the preparation for the release of the case file, the district attorney’s office assembled a small team to examine the case file in its entirety, not only to see what could be released to the public, but also to see if there was any work left to be done in the case, given the amount of time that had passed.

The renewed investigation relied on a form of genetic testing that had not existed when Britton was killed. In 1969, forensic science could not extract or preserve DNA in any usable way.

By 2017, however, advances in molecular biology allowed laboratories to recover genetic material from decades old evidence that had once been considered unusable.

The samples that were conserved from the Britton case were taken from the original swab samples collected at the crime scene. When the samples were reanalyzed, the team concentrated on a technique called Y-STR analysis.

This technique differs from the standard DNA analysis process, as it examines genetic markers that are passed down from both parents. Y-STR analysis identifies the markers that are present on the Y chromosome alone.

And since the Y chromosome is passed down from father to son with very little change, all males belonging to the same paternal line will have the same Y-STR markers.

This technique does not pinpoint a person but can be used to identify a particular line of males from a group of suspects.

In October 2017, the Massachusetts State Police Crime Laboratory finally managed to obtain a usable Y-STR profile from the remaining samples for the first time. This profile was then matched with the entries in the CODIS database, the national DNA database used by law enforcement.

In July 2018, the laboratory received a match with a profile that belonged to Michael Sumpter.

Sumpter was already deceased, but to independently verify the findings, his biological brother, who shared the same Y-STR markers due to their common paternal lineage, was tracked down.

Testing on him revealed that the DNA found at the crime scene matched this paternal lineage and ruled out 99.92 percent of the male population as potential donors. Further testing confirmed that the DNA could not have come from the brother, leaving Michael Sumpter as the lone source.

The murder of Britton is now known to be the oldest cold case ever solved by the Middlesex County police department and was used to link him to a series of rapes and murders in the Boston area that had long remained disconnected to any known perpetrator.

It was later determined that Sumpter had a long connection to the area, having lived in Cambridge as a child, attending local schools, and having ties to the area well into adulthood.

In the late 1960s, he had a girlfriend who lived in Cambridge, putting him in the area on a regular basis during the time leading up to Britton’s murder.

In 1967, less than two years prior to the murder, he had worked on Arrow Street, approximately a mile from Britton’s apartment, which situated him within the same neighbourhood she moved through.

It is believed to be very likely that Sumpter had previously observed Britton, aware of her habits, her schedule, and the patterns of her movements, before attacking her.

The attack seemed to be the work of a predator who had deliberately chosen his victim, observing her habits before breaking into her apartment and killing her in her bed.

Sumpter’s identification, however, does not necessarily represent the end of his violent acts. This was not the first time science had caught up with his crimes either.

In 2002, his DNA was matched to an unsolved rape committed in Boston in 1985. At the time of that attack, authorities said Sumpter had absconded from a work release program.

In 2010, his genetic profile was linked to the 1972 rape and murder of a twenty three-year old woman in Boston. Two years later, the same evidence connected him to the 1973 rape and murder of a twenty four year old victim.

It has been acknowledged that he may have preyed on other victims who have never been identified. The records of the time are still not complete, and there are a number of unsolved cases from the Boston area that share a number of similarities in terms of method and circumstance.

Jane Britton’s murder has finally been named, but it is possible that other crimes committed by the same man have yet to be attributed, and their victims are still waiting for recognition.