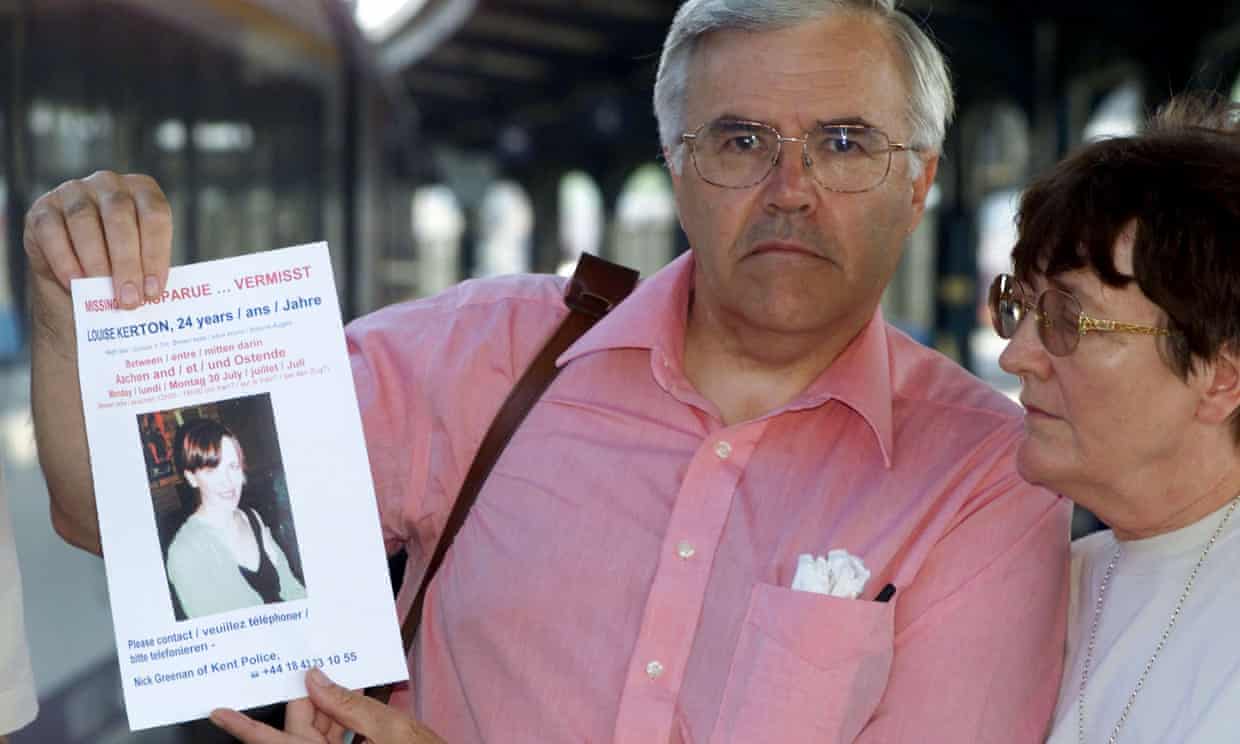

On the morning of July 30, 2001, Louise Kerton was meant to do one simple thing: get on a train at Aachen Hauptbahnhof and start the long trip back to England. She never reached home, and nobody has proven where she went after that.

Her route, according to the account given later by her fiancé’s mother, was Aachen to Ostend in Belgium, then a fast ferry or hovercraft to Dover. After that, she would continue to Broadstairs in Kent, where she lived with her fiancé.

What makes the case hard is how quickly the trail evaporates. Years later, even prosecutors in Aachen were still saying the file could reopen with new leads, because the existing traces were already exhausted.

The summer break that was meant to reset everything

Louise was born in Sheffield on May 17, 1977, and later lived in Broadstairs, a coastal town in Kent. She was 24 when she disappeared, and she was training to become a nurse.

Her family described her as artistic, and she had been diagnosed with dyslexia. In later interviews, her father remembered teachers calling her attentive and engaged, but struggling to present her work in a neat, conventional way.

By the summer of 2001, she had failed part of her nursing exams. Several reports describe her as shaken by that setback, and her father acknowledged she felt depressed about it.

Another weight hung over the family story: Louise had been at the same school as Lucie Blackman, the British woman murdered in Japan in 2000. Her father later said Louise grew up aware of cases like that, and how they leave families stuck in uncertainty.

Louise had been with Peter Simon for years. One early report says they met while ice skating and had been together about six years by 2001, living in Broadstairs until his family moved back to Germany.

In mid June 2001, Louise traveled to Germany and stayed in Swisttal Straßfeld, near Bonn, with Peter’s family. Later German reporting described it as a roughly six week stay, the sort of long visit that blends holiday time with family routine.

Straßfeld, the decision to travel alone, and a pending return

Police summaries circulated in Germany later framed the return trip as tied to uncertainty about her training place in England. The same notice says she decided to travel back alone on July 30, 2001.

That detail matters because it places her in a vulnerable spot: a young woman abroad, under stress about exams, with a long journey ahead. Multiple sources still treat the decision to travel alone as unusual, even if it was practical.

Peter traveled back to England ahead of her. Contemporary UK reporting put that departure on July 26, saying he returned first and waited at the Dover Hoverspeed terminal on the evening Louise was due to arrive.

Later reporting, including a 2021 Guardian account, says he went to England two days earlier to deal with building materials ordered for the family. Both versions agree on the core point: he expected Louise to arrive after him.

The last part of the story that feels solid is the ride to Aachen. A German missing person notice says Louise was driven to Aachen station in a silver Peugeot with British registration by her future mother in law.

That same notice explains why the platform moment becomes a blank. The driver said she could not accompany Louise to the departing train, leaving open the question of whether Louise boarded the service she was meant to take.

Aachen Hauptbahnhof, and the minutes nobody can fill

Louise was last known to be missing from Aachen Hauptbahnhof on July 30, 2001, around midday. German reporting later fixed the intended departure at 12:04 from platform 8 on train number 420, headed toward Ostend.

That train detail reappears across German summaries and appeals, because it is one of the few timestamps investigators could anchor. Police asked passengers from the D 420 service whether they remembered her or saw her with anyone.

If Louise boarded, there should have been witnesses on a long cross border run. If she never reached the platform, then her disappearance could have happened inside or around a busy station area, in a city near the Belgian and Dutch borders.

The problem is that investigators never found independent confirmation that she even arrived there. German reporting in 2011 stated police could not locate witnesses who saw the two women or the conspicuous British plated car at the station.

Early UK reporting also points to an investigative handicap: a lack of CCTV coverage at Aachen station at the time. That meant the usual modern shortcut, rewinding the cameras, was simply not available.

A German poster description, shared in missing person circles, described Louise as about 155 cm tall, slim, with short dark hair. It also described what she wore that day: a white blouse, a long skirt, and black flat shoes.

The same description said she carried a dark shoulder bag and a dark green trolley suitcase. If she walked into the station with that luggage, somebody likely passed her in the concourse or near the platforms.

That is why later reporting keeps returning to the same simple uncertainty: nobody can say, with evidence, that she boarded. The Guardian’s 2021 account put it plainly, noting the speculation around whether she ever got on the train.

Peter expected her in Dover. When she failed to arrive, he contacted her family, and his reaction became part of the case narrative almost immediately.

After Louise failed to arrive in Dover, the case briefly pivoted because German police said they had reports of her being sighted in Aachen in early August 2001. These sightings shaped the first theory that she might still be alive.

According to the missing persons’ bureau in Aachen, she was supposedly seen four times between August 8 and August 11. The reported sightings were spread across ordinary places, which made them sound believable at the time.

On Wednesday, August 8, she was reportedly seen buying a map at a four star hotel in Aachen. That detail was repeated because it suggested planning a route, not hiding in panic or confusion.

Police said she was then seen on Friday, August 10, at Cafi Plattform, described as a place where homeless people receive free food. This is where the “Polish man” detail enters the case record.

The Guardian report described her as being seen with a Polish man at Cafi Plattform. The Independent added a more specific description, saying she was with a “handsome, blond Pole” who cleaned windscreens in the city.

On Saturday, August 11, she was reportedly seen at a nun’s cloister that provides free food, and later that day she was reportedly seen buying food at a petrol station. Those two sightings were treated as part of the same pattern.

The missing report, the police response, and a family feud

Louise was reported missing on July 31, 2001, after she failed to return from Germany. Her father travelled to Germany during the early search and criticised what he saw as limited cooperation from Peter and his relatives.

At that stage, Kent police said they had no confirmed suspicious circumstances and were working with German authorities and the Belgian federal police missing persons unit. Two Kent officers were in Germany as the cross border inquiries began.

Even then, reporters were documenting strain between the families. Peter’s mother said she was too distressed to talk publicly, while Louise’s father argued that media exposure could help bring in witnesses.

At that moment, the case split in two directions. One direction was practical and hopeful: if she was moving around Aachen, then a focused search, more posters, and better witness appeals might bring her into contact.

The other direction was ugly and personal, because Peter Simon began speaking to British newspapers about Louise’s character in ways that enraged her family and hardened their distrust of him almost overnight.

In mid August 2001, he told newspapers she had become promiscuous, “throwing herself at men,” and described her as “sex mad.” He also claimed she had spent time in Aachen cruising bars and nightclubs.

Louise’s father publicly rejected that portrayal, calling it ridiculous and saying Louise was quiet and timid, the kind of person who would sit in a corner when out. The remarks became part of an open war between the families.

Those early Aachen sightings mattered because they implied Louise had safely left the station area and was alive more than a week later. But later German summaries and cold case recaps do not treat the sightings as settled fact.

That leaves a grim possibility investigators later leaned into. If the sightings were mistaken or false, they may have delayed the shift toward a crime investigation, and they may have muddied the timeline at the moment it needed clarity most.

The Simon family’s mistrust of police had a specific backstory that resurfaced in 2001 coverage. Peter’s older brother, Michael Simon, who had schizophrenia, had been tried and acquitted in 1993 for killing a 79 year old woman in Broadstairs.

The Independent reported that Michael Simon’s fingerprints were found on the champagne bottle used in the killing, but a jury acquitted him after hearing explanations about his behaviour and differences from an eyewitness description. The ordeal reportedly left the family suspicious of authority.

Kent police said at the time that they were aware of that history but had no reason to connect it to Louise’s disappearance. Still, the history fed the public tension because it explained why the Simons might avoid press and police.

Louise’s sisters also described Peter’s behaviour as strange in the days after she vanished. One Guardian report quoted her sister Angela calling his comments “erratic,” and describing fears about police treatment and talk of Louise being dead.

The same 2001 Guardian report said Peter called to claim he was a spiritualist and that Louise’s ghost had appeared to him. Years later, the 2021 Guardian account echoed a similar recollection, describing a sister saying he claimed Louise’s ghost visited.

There was also controversy around timing. One German regional recap in 2024 reported that investigators viewed it as suspicious that Peter waited five days to raise alarm, though UK reporting from 2001 shows police were contacted the next morning after she failed to arrive.

The same 2001 Guardian report adds a detail that kept the story alive: after police were contacted, Peter went to London for a few days, and Kent police confirmed he was interviewed in London on July 31.

The letter that sounded wrong, and the case turning darker

One of the most repeated pieces of evidence is a short letter mailed from Germany on July 20, 2001, ten days before Louise disappeared. Louise’s family worried about it because it felt unlike her usual writing.

The Guardian printed the text, which read: “I’m keeping well. Having a lovely time in Germany. It’s very green here, the weather is nice. Don’t worry about me.”

Her father said the message felt too neat and too brief for someone with dyslexia who usually filled letters with corrections and margin notes. To him, the tone raised the possibility that she wrote it under pressure.

At first, German investigators also had reason to consider a voluntary disappearance. A 2011 German report said there were “indications” she might have wanted a fresh start, given the exam failure and emotional strain.

Over time, the lack of any credible contact shifted that view. The same 2011 report said that after months without a sign of life, indications of a crime strengthened, and Louise was listed by Germany’s Federal Criminal Police Office, the BKA, among unsolved murder cases.

That shift is important because it changes how the file is handled. A routine missing adult case can sit, but a suspected homicide carries different expectations and longer institutional memory, even if the trail is cold.

By the first anniversary of her disappearance, prosecutors ordered a large search effort. The 2011 German report described a sweep with almost 200 officers searching gravel pits around Swisttal Straßfeld, and it produced nothing.

Louise’s father argued that the big search came too late. He believed the delay allowed evidence to fade, and he repeatedly urged investigators to focus harder on the fiancé’s family home and statements.

One specific gap kept resurfacing: besides the future mother in law’s account, investigators had no proof Louise ever left Swisttal alive. The 2011 German report emphasised that police never found witnesses for the car at Aachen station.

The camera roll that should not have existed

In late 2002, the case picked up an unusual clue. The Independent reported police found Louise’s camera at her fiancé’s home in Germany, and developed film inside it as part of a stepped up investigation.

The developed images showed groups of people, including elderly people, sitting outside on terraces in bright weather. The Independent said investigators believed the photos were taken in a village in the Bad Zwischenahn area of Lower Saxony.

Investigators said there was no clear reason those photos would be on Louise’s film, and it was unclear who took them. A television appeal asked the people in the photographs to contact police, hoping to trace where the camera had been.

The implication was simple: if the camera travelled somewhere after Louise vanished, then it might map part of her timeline. If someone else used it, that person might have seen her, or handled her belongings.

This kind of clue is fragile. It depends on somebody recognising a scene, a terrace, a face, or a specific event, and being willing to step forward. In many cold cases, that never happens.

Louise’s family also hired private investigators. A later account says they brought in Bob Moffatt, a former Scotland Yard superintendent, and also Dai Davies, described as a former head of royal protection, after they lost confidence in progress.

Those investigators criticised the Simon family for not cooperating and pointed to inconsistencies, while the Simon family denied any involvement. That conflict became part of the public identity of the case.

The file closes, but the case does not end

Aachen prosecutors later described the case as effectively dormant unless new information surfaced. In a 2011 German report, prosecutor Jost Schützeberg said the office could reopen the file if fresh approaches emerged.

A 2024 German recap described the scale of the paperwork: seven main binders and additional files, totaling about 1,500 pages of investigative material built up over a decade. It said the investigation was discontinued in 2011.

That recap also quoted another prosecutor, Alexander Geimer, saying he could not even be sure whether Louise was alive or dead. It captures the reality of this case: uncertainty hardened into permanence.

In the UK, Kent Police have framed their role as supporting rather than leading. In 2021, ITV quoted a Kent Police superintendent saying German authorities remain the lead agency because Louise did not return to Britain.

The same ITV report said Kent officers made enquiries on Germany’s behalf and would pass along any new information. It is a quiet acknowledgement of jurisdiction, and of how borders slow even determined families.

Today, the core facts remain stubbornly small. Louise left a family home in Swisttal Straßfeld, was driven toward Aachen station, intended to board a specific train, and then disappeared without a verified sighting after that point.

Everything else sits in the gaps: the missing witnesses at the station, the absence of video footage, the unanswered question of whether she boarded, and how her camera ended up holding photos from a different region entirely.