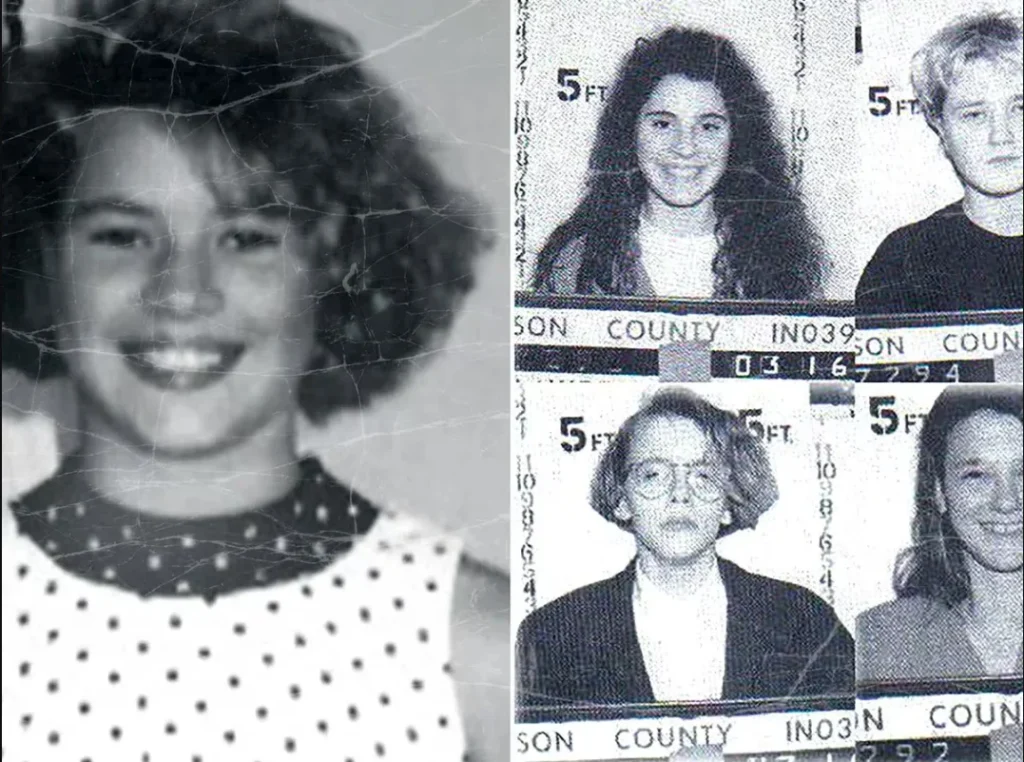

Shanda Renée Sharer was 12 years old when she was kidnapped and killed in southern Indiana in the early hours of January 11, 1992. Four teenage girls were charged as adults, and the case moved fast once police got statements the same night.

The core motive prosecutors described centered on jealousy and control tied to Amanda Heavrin, a girl Shanda had been close to. Melinda Loveless, 16, had dated Heavrin and fixated on Shanda as a rival.

The other three teens were Mary Laurine “Laurie” Tackett, 17, Hope Rippey, 15, and Toni Lawrence, 15. Their roles differed, but investigators said all took part in the criminal confinement that set everything in motion.

Shanda’s family had moved to New Albany, Indiana, in 1991 after earlier years in Kentucky. At school, she met Amanda Heavrin, and their friendship turned into romantic notes and a visible closeness that drew attention.

By fall 1991, Loveless was openly angry about Shanda’s connection to Heavrin. Reports later described public threats and talk of hurting Shanda. Shanda’s parents shifted her to a Catholic school in late November.

On the night of January 10, 1992, Shanda was staying with her father in Jeffersonville, Indiana, where she visited on weekends. That detail mattered later because it placed her away from her mother’s home when the group arrived.

Late that afternoon and evening, Tackett, Rippey, and Lawrence drove from Madison to New Albany to pick up Loveless. Rippey and Lawrence had not met Loveless before that night, but they joined the plan anyway.

At Loveless’s home, the group borrowed clothes and saw a knife Loveless said she intended to use to scare Shanda. Tackett already understood the plan involved more than intimidation, according to later case summaries.

The four drove to Jeffersonville and found Shanda at her father’s house. They introduced themselves as friends of Amanda Heavrin and told Shanda they would take her to see Amanda at a place they called the Witch’s Castle.

The first attempt did not work immediately. Shanda said she had a party to attend and suggested they return around midnight. The group left, crossed into Louisville, and spent time out before returning.

They came back to Shanda’s father’s house around 12:30 a.m. Lawrence refused to go to the door at that point, so Tackett went with Rippey. Loveless stayed in the back seat, hidden under a blanket.

Inside the house, Shanda’s father and stepmother were asleep while Shanda watched television downstairs. Rippey told her Amanda was still waiting at the Witch’s Castle. Shanda hesitated, changed clothes, and then agreed to go.

As Shanda entered the car, Rippey asked her questions about Amanda. Then Loveless emerged from the back seat with the knife pressed to Shanda’s throat and began interrogating her about her relationship with Heavrin.

The car headed toward the Witch’s Castle, also described as Mistletoe Falls, a ruined stone house on an isolated hill above the Ohio River. Tackett talked during the drive, describing local stories tied to the site.

At the Witch’s Castle, Shanda was taken inside and bound with rope. Loveless taunted her and removed rings from her hands, passing them to the others. Rippey took Shanda’s Mickey Mouse watch and played with it.

Tackett escalated the threats by claiming the place was linked to death and that Shanda would join it. Tackett briefly lit a shirt on fire but stopped, worried the flame would be noticed by passing cars, and the group left again.

During the next drive, Shanda begged to be taken home. The group got lost and stopped at gas stations for directions, keeping Shanda covered with a blanket. Lawrence made a phone call during one stop and did not report the kidnapping.

Eventually they reached the Madison area, near Tackett’s home, and pulled toward woods and back roads. The route mattered later because it placed Shanda in Jefferson County, Indiana, where her body was later found.

Tackett led the group to a dark, abandoned building off a logging road in a forested area. Lawrence and Rippey stayed in the car at first. Loveless and Tackett forced Shanda to strip to her underwear and began beating her.

According to case accounts, Loveless slammed Shanda’s face into her knee hard enough to cut her mouth on her braces. Loveless attempted to cut Shanda’s throat with the knife but the blade was described as too dull to do it.

Rippey then came out to help restrain Shanda. Loveless and Tackett stabbed Shanda and then strangled her with a rope until she lost consciousness. They put her into the trunk and told Lawrence and Rippey she was dead.

The group drove to Tackett’s nearby home and went inside to drink soda and clean themselves. They then heard Shanda making sounds from the trunk, showing she was still alive, and Tackett went back out to attack her again.

Around 2:30 a.m., Lawrence and Rippey stayed behind while Tackett and Loveless drove out “country cruising,” heading toward Canaan. Shanda remained in the trunk during that drive, and the assault continued after more stops.

At one stop, the trunk was opened and Shanda was seen sitting up, badly injured and unable to speak clearly. Tackett beat her with a tire iron until she fell silent, and the case record also described a sexual assault during this phase.

The driving and repeated attacks continued for hours. Near daybreak, Tackett and Loveless returned to Tackett’s house, cleaned up again, and woke the others. Rippey asked what happened and Tackett described the violence in detail.

Instead of taking everyone straight home, Tackett drove to a “burn pile” area and opened the trunk again. Lawrence refused to look. Rippey sprayed Shanda with window cleaner and taunted her, according to the account.

The group then prepared to destroy evidence and end the situation permanently. They went to a gas station near Madison Consolidated High School, bought a two liter bottle of Pepsi, poured it out, and refilled it with gasoline.

From there they drove north of Madison, past Jefferson Proving Ground, to Lemon Road off U.S. Route 421. Rippey knew the location. It was a gravel country road with a field beside it, away from town traffic.

Lawrence stayed in the car while Tackett and Rippey carried Shanda, still alive, wrapped in a blanket, into the field. Rippey poured gasoline on her and set her on fire, then they returned to pour the rest.

Afterward, the girls went to McDonald’s around 9:30 a.m. for breakfast and talked about the killing. Lawrence then called a friend and disclosed what happened, which became one of the threads investigators later followed.

Tackett dropped Lawrence and Rippey at their homes and returned with Loveless. Loveless told Amanda Heavrin that Shanda had been killed and arranged for Tackett to help pick Heavrin up later that day.

A friend named Crystal Wathen visited Loveless, and the group told her the story. Loveless, Tackett, and Wathen then picked up Heavrin and brought her back to Loveless’s home, where they repeated the account directly to her.

Heavrin and Wathen did not believe the story at first. Tackett showed them the trunk, including bloody handprints and items left inside, and the mood changed. Heavrin asked to be taken home and Loveless pleaded with her not to tell.

Later that same morning, two brothers, Donn and Ralph Foley, drove toward Jefferson Proving Ground to go hunting. Along the road they saw what they first thought was a mannequin, then realized it was the burned body of a child.

They called police at 10:55 a.m. Investigators arrived, collected evidence, and initially considered theories such as a drug related attack, partly because of how the scene appeared and how difficult identification was due to the burns.

Back in Jeffersonville, Shanda’s father realized she was missing early on January 11. After calling neighbors and friends, he contacted Shanda’s mother in the afternoon. They filed a missing person report with the Clark County sheriff.

That evening, the case broke open from inside the group. At 8:20 p.m., Toni Lawrence and Hope Rippey went to the Jefferson County Sheriff’s office with their parents and gave statements identifying “Shanda” and naming others.

Those statements were described as rambling but detailed enough to connect the body to the missing child report. Sheriff Buck Shipley contacted Clark County, and the agencies aligned the two investigations. Dental records were then used to confirm identification.

Melinda Loveless and Laurie Tackett were arrested on January 12, 1992. Prosecutors quickly announced their intent to try them as adults, and all four girls ultimately faced the case in adult court rather than juvenile court.

Charging decisions reflected who investigators believed did what. Loveless, Tackett, and Rippey were convicted of murder, criminal confinement, and arson. Toni Lawrence pleaded guilty to criminal confinement, tied to the kidnapping stage of the crime.

To avoid a death penalty prosecution, plea bargains became the central path. Toni Lawrence accepted a plea bargain first, in April 1992, and her cooperation became part of the evidentiary base alongside Rippey’s account.

Loveless and Tackett accepted plea bargains in September 1992. Both pleaded guilty to murder, criminal confinement, and arson. Sentencing still involved contested hearings over aggravating factors and mitigation, because prosecutors sought maximum time.

Melinda Loveless’s sentence was affirmed in later court rulings. In a direct appeal decision, the sentencing judge imposed the maximum 60 year term for murder and 20 years for criminal confinement, ordered to run concurrently, consistent with the plea structure.

Laurie Tackett received a 60 year sentence as well, served in the Indiana women’s prison system. Hope Rippey initially received 60 years with 10 years suspended, and the record later shows her sentence was reduced on appeal to 35 years.

Toni Lawrence, described as cooperating early and not present for the final burning, received up to 20 years on the criminal confinement count. Her case is often summarized as the least severe sentence, though it still involved years in custody.

Appeals followed, mainly from Loveless. Her direct appeal reached the Indiana Supreme Court and her sentence was upheld in 1994. Years later, her lawyer filed for post conviction relief arguing severe childhood abuse and deficient representation.

A Jefferson Circuit judge rejected that request in January 2008 and set an eligibility framework that kept the plea intact. An Indiana Court of Appeals ruling later upheld the denial, keeping the underlying conviction and sentence structure in place.

Release dates show how the system handled juvenile offenders tried as adults under the sentencing rules of that era. Toni Lawrence was released on December 14, 2000, after about nine years, and remained under supervision until 2002.

Hope Rippey was released on April 28, 2006, after serving about 14 years. Records describe her remaining on supervised parole for five more years, ending in April 2011, tied to the terms of her release supervision.

Laurie Tackett was released on parole on January 11, 2018, the anniversary date of Shanda’s death, after about 25 years. Reporting at the time described conditions including treatment requirements, limits around children, and supervision.

Melinda Loveless was released on September 5, 2019, after more than 26 years in prison. Post release supervision was set in Jefferson County, Kentucky, and local reporting described her as the last of the four to leave custody.

Taken as a full case file, the key verified sequence is clear. The group used a lie about seeing Amanda Heavrin to get Shanda into a car, then moved her across multiple locations before killing her near Madison the next morning.

The investigation moved quickly because two participants returned with parents and gave statements that pointed directly to the others. Without that decision, the case likely would have taken much longer, given the condition of the body and the rural dump site.