The Sacred Band of Thebes was an elite infantry unit in fourth century BCE Thebes. Ancient writers describe 300 selected soldiers organized as 150 pairs of male partners, kept together as a single formation.

Thebes sat in Boeotia, north of Athens, and often competed with other Greek city states for influence. After Sparta won the Peloponnesian War, Spartan garrisons and alliances shaped politics across Greece, including in Thebes.

In 382 BCE, Sparta seized the Theban citadel, the Cadmea, and installed a friendly regime. Tension lasted until exiles returned, killed key officials, and restored Theban control in 379 or 378 BCE.

Plutarch says Thebes created a permanent corps soon after expelling the Spartans. He credits the commander Gorgidas with forming it, choosing men for ability, and keeping them ready as a dependable core force.

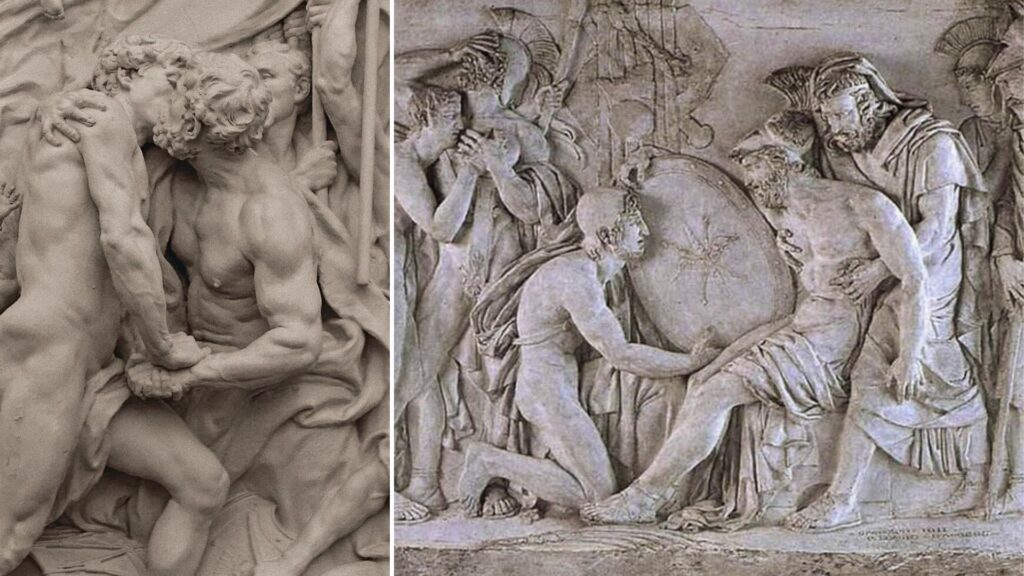

The soldiers fought as hoplites, heavily armed citizen infantry. A hoplite carried a round shield, a spear, and a sword, and moved in a phalanx, where discipline mattered as much as individual skill.

Greek city states relied on citizen levies that gathered for campaigns and then returned to farms and workshops. The Sacred Band functioned as a standing unit, allowing regular training, steady leadership, and a shared identity within the army.

The unusual feature was its pairing. Plutarch describes 150 pairs, often framed as an older lover and a younger beloved, and other ancient writers also connect the unit to bonds of affection and loyalty.

Modern labels can mislead when applied to ancient societies. Greek writers described relationships through roles and customs that varied by city and period, and the evidence does not let historians describe every pair in modern terms with certainty.

Several sources treat the unit’s bonds as deliberate, not rumor. Athenaeus writes of lovers and favorites, and Polyaenus describes men devoted to each other through obligations of love, suggesting a recognized tradition.

Plutarch links the unit’s sacred character to vows at the shrine or tomb of Iolaus. He also reports that Aristotle knew the spot as a place where lovers and beloved pledged faith.

The unit’s name appears in surviving Athenian oratory. Dinarchus, writing in 324 BCE, mentions the Sacred Band and links it to Theban leaders and the Spartan defeat at Leuctra.

Thebes rebuilt its influence through the Boeotian League, a federation of nearby towns. These campaigns forced out Spartan aligned garrisons and restored Theban leadership in the region, creating repeated clashes between Theban forces and Spartan detachments.

Pelopidas, a leading Theban statesman and general, became closely associated with the unit. Some accounts say Gorgidas first dispersed the pairs through the line, but later commanders kept them together under Pelopidas for decisive use.

The Sacred Band’s early test came at Tegyra, often dated to 375 BCE. Plutarch’s Life of Pelopidas gives the main narrative, describing Pelopidas moving with the Band and cavalry and meeting a larger Spartan force.

Ancient battle numbers vary, but Tegyra’s imbalance is clear in the sources. The Sacred Band had about 300 hoplites, while the Spartan garrison is described as two companies that could total over a thousand.

Facing the imbalance, Pelopidas formed his infantry in a dense block. The Theban cavalry charged first, and when the phalanxes met, the compact formation broke through at contact and struck the exposed flanks.

The Spartans retreated toward Orchomenus, and the Thebans, close to enemy ground, limited pursuit. Tegyra did not end the war, but it showed Spartan troops could be beaten in a set engagement.

Ancient authors treated Tegyra as a warning sign. Diodorus records it as the first Theban trophy over Spartans in a proper battle, and Plutarch framed it as a prelude to Leuctra.

In 371 BCE, tensions between Sparta and Thebes escalated into a major confrontation near the village of Leuctra in Boeotia. Sparta’s king Cleombrotus led the Spartan army, while Thebes fielded forces under Epaminondas and other leaders.

Greek battles often involved two phalanxes pushing in a straight line, with elites on the right. Epaminondas broke the pattern by stacking Thebes’ best troops on the left to hit the Spartan right first.

Some accounts say Epaminondas deepened the left wing to about fifty ranks, far deeper than the usual eight to twelve. The rest of the line advanced more slowly, creating an oblique attack that concentrated force where Sparta was strongest.

Sources place Pelopidas and the Sacred Band on the extreme left beside Thebes’ strongest infantry. The battle opened with cavalry fighting, and the stronger Theban horse drove Spartans back into their own ranks, disrupting the line.

With the Spartan line unsettled, the Theban left struck the Spartan right. Sources describe the Sacred Band pressing at the decisive point as the mass advanced, and the Spartan king was killed in the front ranks.

The Spartan right collapsed, and the rest of the line withdrew once the elite was beaten. Leuctra mattered because Sparta’s reputation for invincibility was broken, and its alliance system started to unravel.

Thebes used its new position to pressure Spartan allies and reshape the balance of power in Greece. Epaminondas led campaigns into the Peloponnese, and Theban influence spread into regions that Sparta had controlled through garrisons and treaties.

The Sacred Band remained active during this Theban ascendancy. It served as a reliable assault unit and a guard for commanders, and its reputation grew because a small, identifiable roster was tied to famous battles.

Pelopidas’ career also illustrates how intertwined military and politics were in Greek city states. He negotiated alliances, intervened in Thessalian disputes, and fought campaigns outside Boeotia, showing that Theban power depended on movement and fragile agreements.

Pelopidas died in 364 BCE at Cynoscephalae in Thessaly during fighting against Alexander of Pherae. Accounts vary, but his death removed a commander closely linked to the Sacred Band and to the political strategy behind Thebes’ rise.

In 362 BCE, Thebes fought at Mantinea against a coalition of rivals. Epaminondas was mortally wounded after a tactical success, and his loss, like Pelopidas’ earlier death, weakened the leadership behind Theban dominance.

After Mantinea, Thebes remained important but lacked the same ability to impose its will. Greek politics shifted toward new threats, and Macedon, a kingdom to the north, intervened more directly under its king Philip II.

Philip reorganized his army with long pikes and coordinated cavalry, creating a force that differed from the traditional citizen phalanx. He also used diplomacy, hostages, and alliances, exploiting divisions among Greek cities that were tired of war.

By the late 340s BCE, Athens and Thebes set aside rivalries to oppose Philip. The alliance reflected fear of Macedonian control more than affection, and it produced a combined army that marched to confront him in central Greece.

The decisive clash came at Chaeronea in 338 BCE in Boeotia. Philip commanded the Macedonian army, and his son Alexander held a key role. The allied Greeks formed a line with Athenians and Thebans in separate sectors.

Ancient narratives of Chaeronea vary, but most agree that Macedonian discipline and cavalry coordination broke the allied line. Some accounts describe Philip drawing the Athenians forward, while Alexander’s attack struck a critical point against the Theban side.

Later writers link the Sacred Band to the Theban position at Chaeronea. Plutarch says the unit was destroyed there, and Diodorus reports heavy allied losses, implying a hard fight that ended with a sweeping Macedonian victory.

Stories developed about Philip’s reaction after the battle. Some later retellings say he admired the fallen Thebans, though the sources for those emotions are later and should be treated cautiously.

Chaeronea marked a political shift. Philip imposed a new order through a league of Greek states under Macedonian leadership, and the major cities accepted limits on independent war making, even as they kept local institutions.

In 335 BCE, after a revolt, Alexander destroyed much of Thebes and sold many inhabitants into slavery. The event ended Thebes as a major power and shaped how later Greeks remembered its brief supremacy.

The memory of the Sacred Band survived through literature and monuments. Pausanias, writing in the second century CE, describes a large stone lion near Chaeronea placed above a common grave for Thebans who died fighting Philip.

Polyandrion means a communal tomb for men killed in battle. Greek cities sometimes honored war dead with collective burials and public markers, tying civic identity to sacrifice and giving later travelers a site to connect with famous events.

Over time, the Lion of Chaeronea became damaged and partly buried. In 1818, the architect George Ledwell Taylor, using Pausanias as a guide, found fragments when his horse stumbled and recognized the lost lion.

Nineteenth and twentieth century excavations and restorations followed, and the monument was reassembled. The site drew attention because it tied written history to an object on the landscape that people could visit.

Excavations near the lion found a rectangular enclosure with a mass burial. Reports describe 254 skeletons laid out in rows, a number close to the famous 300, which encouraged identification with the Sacred Band, though membership is debated.

Some scholars accept the link because of location, dating, and the orderly burial. Others note Pausanias did not name the Sacred Band in his description of the lion, and modern work has questioned who the 254 dead were.

The gap between 254 skeletons and the ideal 300 invites caution. Bodies may have been lost, removed, or buried elsewhere, and the famous unit may not have died to the last man, despite later claims.

The Sacred Band’s reputation rests on the idea that cohesion matters in close combat. In a packed line of shields and spears, men depended on those beside them, and commanders valued groups that could hold position under pressure.

Plutarch presents the pairing system as a tool for steadiness. He suggests a man would avoid shameful conduct under the eyes of a beloved, and that mutual concern could strengthen willingness to endure fear and fatigue in formation.

Greek writers did not invent this argument only for Thebes. In Plato’s Symposium, a speaker praises the military potential of an army composed of lovers, a philosophical claim that reflects broader Greek assumptions about honor and motivation.

The Sacred Band also became a vehicle for discussing merit and class. Plutarch says Gorgidas chose men for ability, regardless of background, and that quality came from selection and training rather than inherited status.

Daily life is harder to recover. Ancient sources do not give a schedule of drills, rations, or pay, and archaeology cannot reveal private relationships, so reconstructions must stay within what the texts report.

How the Band was deployed can vary in scholarship. Some accounts emphasize garrison duty in the Cadmea when not campaigning, while others stress its use as a mobile strike force placed at decisive points.

The best documented pattern is that it operated under trusted commanders. Gorgidas is linked to its formation, and Pelopidas is linked to its battlefield leadership, while Epaminondas shaped the broader tactics that gave Theban forces victories.

The unit’s story shows how quickly Greek power could rise and fall. From liberation in 379 or 378 BCE to defeat at Chaeronea in 338 BCE is about four decades, and many key leaders died earlier.

Modern writing often highlights the Band in discussions of same sex relationships in antiquity. The evidence supports erotic pairing in the unit, yet the meaning of those bonds remains tied to Greek norms and language.

The most stable facts are anchored by multiple sources and battlefield outcomes. A Theban elite unit existed, fought under Pelopidas, gained fame at Tegyra and Leuctra, and was linked by later writers to death at Chaeronea.

The remaining uncertainties are also part of responsible history. Exact recruitment methods, the personal lives of the soldiers, and the precise identity of the 254 skeletons cannot be proven beyond doubt, so careful language matters.

Remaining uncertainties still matter. Recruitment methods, personal lives, and the identity of the 254 skeletons cannot be proven beyond doubt, so careful language is always needed when telling the story.

The Sacred Band is remembered by name, by a distinctive organizational claim, and by a memorial landscape. That combination keeps it present in histories of Greek warfare and social life.