The search underwater had already produced a disturbing result. Divers who were qualified to enter the gated section kept surfacing with the same message, they could not find Ben McDaniel, and they could not find signs that he had been where he was supposed to be.

So investigators widened the net above water. Over 36 days, teams moved across the resort and its surroundings with cadaver dogs, scent dogs, searchers on foot, horse mounted teams, and even a helicopter, checking every place a person could go after leaving the water.

Ben’s black three quarter ton pickup became the anchor point for everything that followed. It was found locked. Inside were his wallet, phone, driver’s license, and a large amount of cash, described as $1,100 by family, while some reports put it closer to $700.

Nothing around the truck suggested a struggle. There was no obvious damage, no sign of a hurried departure, and no trace of someone forcing entry. What stood out instead was time, the truck sat in the same spot from Wednesday night to Friday morning.

Ben’s family was furious that it took two days for anyone to report him missing, but the timeline looks different when placed inside the routine of Vortex Spring. Ben was there constantly, often staying all day and sometimes later than others.

The truck had been parked for about two and a half days, while Ben himself had been unaccounted for closer to 36 hours when the alarm was finally raised. In a busy summer resort, a familiar vehicle can blend into the background.

Eduardo Taran was the employee most likely to notice because he knew Ben and spoke with him. Yet Eduardo did not stay late on Wednesdays, and Thursday was a hot, crowded day with heavy activity that made gaps less obvious.

On Thursday, no divers rented the key or reported anything unusual about the gate. The day ended around 5 or 6 p.m., and employees went home with nothing visibly wrong. By that point, about 24 hours had passed since Ben was last seen.

There is also the hard reality of solo diving and silence. Ben left no written dive plan and did not arrange for anyone to watch for his return. Even if someone noticed earlier, the odds of a rescue from a cave emergency were extremely low.

The parking location raised its own questions. The divers’ lot sat near an area that was not technically Vortex Spring property, tied to the Dockery family, the original owners. Lowell Kelly purchased the resort after the Dockerys foreclosed in 2007.

The Dockerys still owned a house on the premises and one dock entrance to the water. They allowed guests to park and use that dock, which could bypass paying certain fees. Some divers believed Ben’s truck was parked on Dockery property.

It remains unclear if Ben knew the property lines, but some suspected he parked there intentionally and used that dock to avoid the $25 daily diving fee. Whether or not that is true, it added another layer of uncertainty to an already murky story.

Search dogs were brought in next, and for the family, they offered something the cave would not. A clear signal. Several cadaver dogs and scent tracking dogs swept the resort, the buildings, the campgrounds, the woods, and areas near the waterline.

Ben’s father Shelby later said one dog alerted at the surface, jumped in, and began swimming toward the cave entrance. The handler reportedly told him it was unusual behavior, and the family took it as strong evidence that Ben was in the cave.

Then the argument began, because the dog story came with competing claims about training. Recovery diver Kevin Carlisle said the dogs brought in were not trained for water detection. He later disputed Shelby online about whether the dogs were properly qualified.

Carlisle claimed the recovery divers had recommended a trusted set of dogs with known water search training, but a different group may have been used because they could arrive sooner. Under stress, the family believed a key sign was being dismissed.

It is also unclear which dog did what. Both cadaver dogs and scent tracking dogs were involved, but reports varied on whether a dog truly alerted to decomposition or simply followed an expected path toward the docks and diver entry areas.

Beyond the dock area, the dogs did not produce a wider trail. There were no strong scent lines through the woods or around buildings that pointed to Ben leaving the water and walking away on foot, at least not according to this account.

Dogs are powerful tools, but they are not perfect. They can alert to please a handler or react to excitement in a new environment. A working dog arriving at a busy outdoor resort can behave unpredictably, even with good training.

Investigators also had to consider the spring’s flow. If Ben had died in a way that allowed his body to be pushed out of the cave, it could have moved into Blue Creek, then to Sandy Creek, then to the Choctawhatchee River, and eventually toward the Gulf.

That possibility sounds dramatic, but the geography pushes back. Depending on water level and rainfall, the creeks can narrow to shallow, slow stretches. A body typically begins floating days after drowning, and Ben would have been weighed down by heavy gear.

Searchers still worked the route. Cadaver dog teams checked along Blue Creek toward the Choctawhatchee River, including wooded areas. The search did not turn up evidence of Ben, and the timeline made a long journey to open water unlikely.

Back at the beach home where Ben had been staying, investigators and family found a different kind of trail. Emily Greer discovered books spread across his bed, covering recreational diving, technical diving, and cave related topics, suggesting constant study.

The books showed effort, but they also suggested something riskier, learning complicated skills from reading rather than supervised instruction. In high hazard sports, theory without drilled practice can create confidence without capability, especially under stress.

More unsettling was Ben’s dog, Spooner. Spooner was found inside, thirsty and hungry. The family described Spooner as a rescue dog that Ben would never abandon. He often took her with him, but she stayed home that Wednesday.

The family believed Ben would not leave her without arranging care, especially if he planned to be away longer than a day. To them, Spooner’s condition argued against a planned disappearance and pointed back toward a sudden event.

The home also contained Ben’s cave maps, notes, calculations, and extensive dive logs. On the surface, the paperwork suggested discipline. Yet the deeper people looked, the more the details raised questions about how he trained and what he claimed.

Early entries in his log were described as neat. Over time, the writing became messier and harder to read. He started classes but did not finish them. He recorded new skills, yet moved on quickly, with little time spent practicing fundamentals.

One example cited was his approach to side mounted tanks. He began experimenting with the configuration, and almost immediately his logs suggested he was pushing into more advanced techniques that involve moving tanks ahead of the body in tight spaces.

Those techniques are considered extremely advanced. The concern raised here is not that Ben was curious. It is that he appeared to jump from new skill to harder skill without building repetition, muscle memory, and calm competence.

The numbers fed that worry. Over roughly four months, Ben logged more than 250 dives, which implies two to three dives per day on average. If he took breaks, like traveling home for his mother’s birthday, he would need even more dives on other days.

Many divers take years to reach that number. Online discussions questioned whether Ben was truly mastering skills or simply accumulating entries. In overhead environments, skill has to be automatic, because hesitation wastes air and panic multiplies problems.

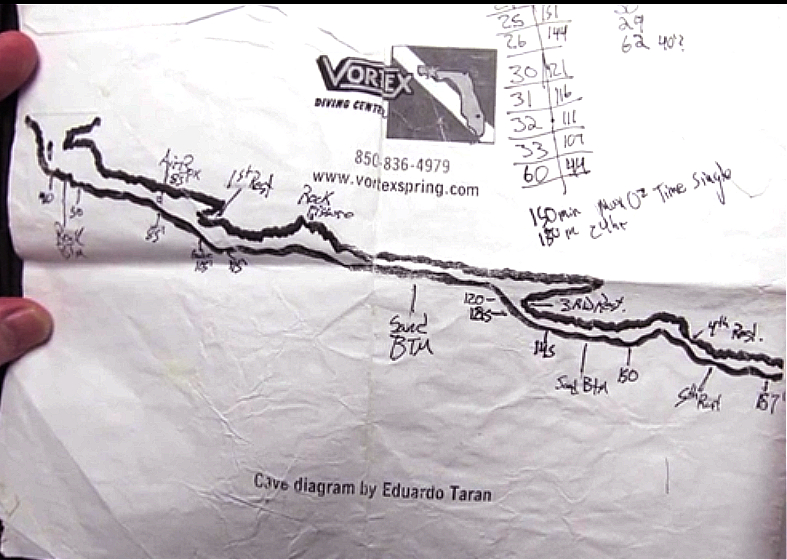

His maps raised further doubts. Ben had drawn his own cave maps in diver shorthand. Recovery divers said the maps contained errors. Edd Sorenson reportedly said Ben marked an opening that did not exist, and that the area was solid limestone.

Kevin Carlisle mocked the premise of mapping the system at all, given its general layout. He was quoted saying the cave was essentially a straight line with one turn, and that bigger, more advanced divers often choose other sites.

Then came the binder that made many people in the diving community furious. Ben had a binder of temporary certification cards, including cards for classes he did not complete. Some were reportedly written in his own handwriting.

According to this account, Ben had called dive shops and excursion groups asking about employment, using the temporary cards as proof of experience. Friends also believed he was already an instructor, a belief that did not match the certifications described here.

One detail stands out because it is concrete. In his final phone call, Ben left a voicemail for a friend saying a shop wanted to employ him as an instructor or divemaster. This account states that claim was untrue.

When Sorenson cut short a vacation to assist, a family friend made a remark to media that irritated divers. The friend said Sorenson was the most experienced cave diver around, more experienced than Ben, which implied Ben had been presented as nearly equivalent.

For trained divers, the comparison was insulting and alarming. Ben was not certified to enter the cavern or cave beyond the basin at Vortex Spring under the rules described here. Yet his circle appeared to believe he was operating at a far higher level.

The debate widened into a broader question of responsibility and safety. Scuba diving culture places responsibility on the diver, especially in caves. The rule repeated by divers is simple, never dive beyond personal limits.

Limits are not just depth numbers. They include training, physical condition, equipment maintenance, skill with tools, ability to read instruments, and ability to stay calm during emergencies. In this worldview, the diver owns the consequences of failure.

Cave diving heightens that philosophy. It is viewed as unforgiving, and fatalities often involve people who lack training. Divers argue that pushing beyond limits will eventually get someone killed, whether on the first attempt or a later one.

A dive buddy is usually treated as essential, yet some people dive alone. Even then, many divers say each person is effectively alone because each person must manage their own air, buoyancy, navigation, and emergency actions.

Panic is the threat that turns small errors into deaths. Panic can be triggered by a mask flooding, losing a regulator, running low on air, currents, losing contact with a line, separation from a buddy, or disorientation in low visibility.

In open water, a panicked diver may bolt upward, which can be deadly due to rapid ascent injuries and decompression problems. In a cave, there is no straight ascent to safety, so panic expresses itself differently and can become more dangerous.

A panicked diver can flail, kick, and thrash, sometimes ripping off equipment from themselves or others. Some divers describe desperate behavior that looks irrational, including pulling off a mask or removing a regulator even though it worsens the crisis.

In caves, panic can also drive people into tight spaces. Without a visible exit, a frightened diver can wedge into cracks or corners, chasing an imagined route or simply reacting physically to stress. This possibility is discussed often in Ben’s case.

The darker rule in cave culture is what happens if a diver becomes unresponsive. A buddy may attempt a tow only if there is enough air, strength, and training to survive the rescue. If not, the buddy may mark the location and leave.

That sounds brutal to outsiders. Divers describe it as survival logic. A cave can easily claim two people instead of one, and panic can cause a drowning diver to endanger a rescuer. These are the risks cave divers accept when entering.

Some people suggested Vortex Spring should have stronger safety measures, like extra lighting, permanent lines, emergency alarms, or air stations. Divers pushed back, arguing that these systems create new hazards and are hard to implement.

Lights can become a problem in silted conditions because glare can blind a diver who cannot control it. Permanent lines can create entanglement risks and remove the ability to cut and adapt. Air stations raise questions about gas type, placement, and maintenance.

Tracking and alarm systems sound useful until a diver is in zero visibility and cannot find the device, or cannot safely reach it. Even if an alarm goes off, the next question becomes who is qualified to enter and attempt a rescue.

This is where the story swings back to Ben himself. When the case hit the media, family members described him as fearless. Divers online responded that fearlessness is not the same as preparation, and they focused on the certifications he actually held.

Ben had been diving since adolescence and clearly loved the sport, but this account says he was only certified for open water diving to about 100 feet. He lacked certification for overhead environments, cave restrictions, deep technical mixes, and advanced setups.

He did start classes. The issue described here is that he did not finish many of them. Without instructors, critique, and repeated drills, he could not fully build the habits needed to handle a cave emergency while maintaining controlled breathing and judgment.

Deep and restrictive dives require planning that is both mental and mathematical. Gas selection, tank placement, depth limits, decompression planning, and timing all matter. Without instruction, there is no one to check calculations for errors.

The key skill is not bravado. It is automatic response. In a silt cloud, a diver may need to stop moving and wait for settling, even while adrenaline screams to flee. Without training, a person burns air and choices collapse.

Online divers described what that scenario could feel like. One user imagined a low air situation at depth with zero visibility, crawling out without knowing orientation, each movement worsening the silt, and disorientation pushing the mind toward instability.

Another instructor who met Ben is quoted describing Ben asking about cave classes and losing interest when he heard the price. The instructor said Ben had also tried to dive the Oriskany wreck but was turned away because his certification only allowed 100 feet.

Training is expensive, but Ben’s parents were supporting him financially during a sabbatical meant to stabilize his life. This account suggests they would have supported further certifications if he asked, raising the question of why he did not seek that help.

Ben also told his father Shelby he did not really have friends at Vortex Spring and was not connecting enough to form dive buddy relationships. Shelby encouraged him by saying he was talented enough to dive solo, a comment that later sits uneasily.

Some speculated Ben lacked a buddy because his personality clashed with other divers. Others believed he simply preferred independence. Either way, the outcome was the same, he was alone on the dive that mattered.

Two weeks before Ben vanished, a dive video captured him in the Piano Room area. The footage was taken by Nik Vatin, a regular at Vortex Spring who later assisted in the search, and who was also connected socially to Eduardo Taran.

Ben later posted about that night on Facebook, according to forum quotes. He wrote that he had interrupted a video shoot, called it a fun solo sidemount cave dive, and described planning a deep penetration solo dive with multiple tanks and long duration.

The post included specific numbers, eight tanks, a 232 minute dive, depth around 148 feet, and penetration to the end of the system around 810 feet. The tone suggested confidence, even casual pride, in what he was attempting.

Divers on forums responded by pointing to the video and questioning his buoyancy control. They believed he struggled with the side mounted setup, and said the footage showed a large diver with complex gear in an overhead environment.

The contrast mattered because his writing implied mastery, while the footage suggested a steep learning curve. Divers saw the casual phrasing as embellishment, and treated it as another sign that he was overestimating his readiness.

Then investigators and divers pieced together how the gate was being tampered with. The gate is described as welded rebar in a tight area, with a door section chained like a hinge and locks placed on one side for controlled access.

The claim in this account is that Ben did not simply pull at locks. He removed chains and locks from the hinge side, a section not meant to open, and replaced them with his own. That allowed him to unlock his side and enter quietly.

When Eduardo encountered Ben on the night of the disappearance, the account suggests Ben was unlocking his secret locks, expecting to be alone. Eduardo interpreted what he saw as Ben forcing the gate, not using a hidden lock system.

That changes the meaning of Eduardo’s decision. Even if Eduardo had refused to open the official gate, the hidden locks meant Ben could likely have entered anyway. Eduardo’s act may have altered timing, but it may not have altered access.

Divers viewed the secret lock system as a mix of confidence and frugality, a cheap method to bypass the certifications required to rent the key. It also suggested planning, repeated attempts, and comfort with breaking rules inside a dangerous environment.

At the core, the question becomes psychological as much as physical. Why would someone skip finished training, rush through skills, carry questionable temporary cards, claim instructor level ability, and then enter a restricted cave zone at depth alone.

Divers offered an answer that was blunt. They believed Ben embellished to appear like a bigger deal than he was, to family, to friends, and possibly to himself. They also believed ego can turn an easy cave into a deadly one when something goes wrong.

Kevin Carlisle, one of the recovery divers, was quoted describing attitude as everything in diving, and warning that ego creates danger. He emphasized that Vortex can feel safe until the moment it stops being safe beyond the gate.

The final point in this account is not subtle. Ben knew he was not supposed to be in the cave because he lacked certification. He knew training was required. He also knew the gate existed to keep people like him out.

Yet he still planned for it, manipulated access, and pushed into the restricted area. Whether the end was accident, panic, a decision made in fear, or something else entirely, the record here paints a diver consciously breaking rules at depth.

Part 4 follows with a closer look at Ben’s gear and the suspicious stage tanks that were found during the search.