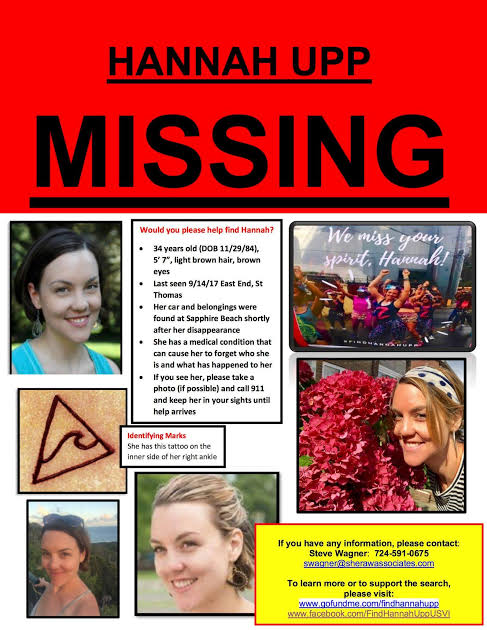

Hannah Upp left her apartment on the east end of St Thomas on a Thursday morning in September 2017. She told people she planned to swim before helping set up her classroom. She drove toward Sapphire Beach and did not come back.

Her car was later found in the beach parking area. Inside were her phone, wallet, passport and other personal items, arranged in an orderly way. Workers at a nearby bar noticed her sandals and sarong placed together on a stool.

Hannah was thirty two and taught at a Montessori school on the island. She knew the water and local routines. Her friends said a quick swim before work was normal for her, not a sign of risk or unusual behaviour.

When she did not arrive at school, colleagues tried her phone and then contacted her roommate. It became clear she had left without the basic items most people carry for any trip. Calls went unanswered and the familiar cycle of worry started again.

For people around her, this disappearance did not stand alone. Hannah had gone missing twice before, first in New York and then in Maryland. Both times she was later found alive, with almost no memory of where she had been.

Those earlier episodes led doctors to diagnose a condition known as dissociative fugue. People in fugue can travel, speak and carry out daily tasks while separated from their usual sense of identity. When the episode ends, they often cannot recall what happened.

Public records show that Hannah was born in Oregon and grew up in a religious household. She excelled at school, studied languages and attended Bryn Mawr College. Friends described her as thoughtful, organised and committed to teaching long before she entered a classroom.

By 2008 she was living in New York City, preparing to teach middle school students in Harlem. She had an apartment in Hamilton Heights, a regular running route and detailed plans for the new school year pinned across her walls and notebooks.

On August twenty eighth that year, Hannah left the apartment in running clothes. Her roommate later found her purse on the bedroom floor. Inside were her wallet, passport, MetroCard and phone. There was no sign she had packed for any extended trip.

When she failed to appear for the first day of classes, coworkers alerted the school administration and then police. Flyers with her photograph went up across the city. Her family flew in and met detectives in Harlem to review any possible leads.

Within days, footage from security cameras began to surface. Recordings from an Apple Store in midtown showed Hannah walking up a staircase and checking email on a public computer. Other cameras captured her visiting a gym and using an ATM.

To people searching, the images were both reassuring and confusing. She moved calmly, without visible distress, and did not seem to be hiding. At the same time she made no effort to contact her mother, friends or colleagues who were walking streets with her photograph.

Nearly three weeks after she first went missing, a Staten Island ferry captain noticed what looked like a body in the water near the southern end of Manhattan. Deckhands pulled a woman from the harbour. She was face down, wearing only running clothes and still breathing.

Rescuers later said her skin showed signs of sun exposure on one side, as if she had spent long periods exposed to light. She was taken to a hospital, hypothermic and severely dehydrated. Staff initially did not know her identity.

When Hannah regained fuller awareness, she could remember leaving for her run. The next clear memory was waking in the hospital to see her family relieved and emotional at her bedside. The twenty days between remained largely blank to her.

Doctors reviewing her case diagnosed dissociative fugue, a rare condition placed within the group of dissociative disorders. In this state, people may travel, perform tasks and interact with others while their usual autobiographical memory is disconnected or suspended.

Media coverage at the time focused on the unusual nature of the disappearance. Some reports emphasised the sight of her checking email while listed as missing. Later, specialists criticised that tone as misunderstanding how dissociative conditions can affect behaviour and decision making.

In the months after New York, Hannah tried to rebuild her life. She continued to teach, stayed in contact with friends and worked with therapists to understand what had happened. There was no simple test or scan that could guarantee the episode would not return.

By 2013 she had moved to Maryland and taken a position as a teaching assistant at a Montessori program in Kensington. Colleagues there described her as reliable and engaged with students. The memory of New York remained part of her history, but daily life appeared stable.

On September third, Hannah was last seen near Kemp Mill Road and Glenallan Avenue just before eight in the morning. She had left for work as usual. She did not arrive. When she failed to return home, her mother reported her missing to local authorities.

Police in Montgomery County opened another missing person case, noting her previous disappearance and diagnosis. Some of Hannah’s belongings were later found near a footpath by a shopping area. Officers warned that she might be confused and in need of medical help.

Two days after she vanished, Hannah called her mother from the area of Georgia Avenue and Shorefield Road. A passerby had lent her a phone. She sounded uncertain about where she was. Her mother drove to the intersection and picked her up.

Once again Hannah had limited recall of the missing period. Reports from that time mention a creek in the Wheaton Glenmont area and a shopping cart nearby, though official statements do not describe any injury or criminal activity. She returned home physically safe and under medical review.

For families and clinicians, cases like this present difficult questions. Law enforcement operates within frameworks built around voluntary disappearance, crime and mental health crises that follow more predictable patterns. A person who vanishes, appears on cameras and later returns with no memory does not fit easily.

Hannah had now disappeared twice in five years, each time linked to a probable fugue episode. That record shaped how officials and relatives interpreted her decisions. It also influenced how she saw herself, as someone whose own memory could not always be trusted.

In 2014 she relocated to St Thomas to teach at a small Montessori school. Friends said the island offered a slower pace and a sense of community that appealed to her. She swam, hiked and became part of local routines tied to school and church.

By 2017 she was preparing for another school year when a series of major storms formed in the Atlantic. Hurricane Irma struck the island in early September, causing damage and disruption. Residents worked to repair buildings and secure supplies while also watching forecasts for the next system.

On September fourteenth, Hannah left home in Pillsbury Heights in the morning. She told a colleague by text that she planned to swim at Sapphire Beach before coming to school to help set up classrooms. That was the last confirmed direct communication from her.

When she failed to arrive, coworkers drove to the beach area. They found her car in the lot. Inside, her wallet, passport, phone and other items were in place. At a bar nearby, staff pointed out a pair of sandals and a sarong left together on a stool.

Unlike the earlier episodes, there were no later camera sightings or confirmed encounters. Search efforts began on land and water. Friends, colleagues and volunteers combed the shoreline, trails and surrounding hills. Local authorities coordinated with the Coast Guard as another hurricane approached the region.

The conditions limited what could be done. Rough seas and incoming storms reduced safe operating windows for boats and aircraft. Debris from earlier damage complicated ground searches. After a point, official teams had to scale back activity as resources shifted to broader disaster response.

Hannah’s mother travelled to St Thomas and joined the search. She met with police, volunteers and local officials, walked the beaches and handed out flyers with her daughter’s photograph. Each small lead was checked, but none produced a verified sighting.

In the months that followed, information about the case settled into a few fixed points. Hannah was last seen leaving home that morning. Her car and belongings were found at Sapphire Beach. No body was recovered and no one has been charged with any crime involving her.

The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System lists her as missing, last seen on September fourteenth, 2017. The entry notes her previous episodes of dissociative fugue, her age, height and the specific location on St Thomas where she was reported. The case remains open.

There are recurring questions that appear in discussions of Hannah’s disappearances. One is how far dissociative fugue alone can explain them. Another is whether the final episode in St Thomas should be viewed through the same lens as New York and Maryland.

In 2008 and 2013, Hannah was found alive within days or weeks, in areas reachable on foot from where she had last been seen. There is no direct evidence that she intended harm to herself. Her episodes ended with hospital observation and family support.

The geography of St Thomas introduced different risks. Strong currents, reefs and storm conditions can turn a short swim into a dangerous situation even for capable swimmers. The hurricanes that followed her disappearance complicated any later attempt to reconstruct what might have happened in the water.

There is also the possibility that another fugue episode began that morning, leading her away from the beach rather than into it. In that scenario, she may have walked inland or along roads while the island prepared for worsening weather and eventual evacuations.

No confirmed sighting supports any single explanation. A set of human remains found on a nearby beach in 2018 could not be reliably linked to her. Without identification, that discovery did not change the official status of the case or provide closure to her family.

Cases like Hannah’s highlight gaps where medical knowledge, policing and public understanding meet. Dissociative fugue is rare and often portrayed in extreme or inaccurate ways. Missing person systems are built more for clear categories than for people who vanish while still functioning in public spaces.

Her story also raises questions about risk and independence for people with conditions that affect memory or identity. After New York and Maryland, Hannah still wanted to live, teach and travel on her own. Her choices sat at the intersection of personal freedom and safety concerns.

More than seven years after she left her apartment on St Thomas, the record remains sparse. A short drive, a parked car, belongings left in place and a pair of sandals and a sarong near a bar. Beyond that, the timeline stops.

For her mother, friends and former students, the absence is not abstract. It shows up in unopened classroom doors, unanswered messages and yearly reminders of dates. The public record preserves only fragments, while the main facts of her final disappearance remain unresolved.