On a summer weekend in 1960, four teenagers pitched a tent beside a quiet Finnish lake. By the next afternoon three of them were dead and the fourth was barely alive. More than sixty years later, no one can say for sure who attacked them.

Lake Bodom lies outside Helsinki, near the city of Espoo, ringed with birch trees, reeds and small coves. Families swam there, couples picnicked there. In Finnish crime history, though, the name Bodom has become shorthand for a single brutal mystery.

The four campers came from nearby Vantaa. Eighteen year old best friends Seppo Boisman and Nils Gustafsson planned a night away with their girlfriends, fifteen year olds Maila “Irmeli” Björklund and Anja “Tuulikki” Mäki. They loaded one small tent, some food, drinks and a radio onto two motorcycles.

It was early June, the season of white nights when the sun barely dips below the horizon and the sky stays silver instead of dark. People remember that weekend as unusually warm. The teenagers chose a small peninsula on the south shore of Lake Bodom and set up their tent.

Witnesses later recalled the group talking, laughing and playing music as evening slid into that strange half light. At some point they were seen fishing from the shore. Nothing about their behaviour looked unusual. They simply seemed like four teenagers enjoying a night of freedom.

Somewhere between four and six in the morning, while most of Finland slept, something went very wrong. The exact sequence of events has never been reconstructed with certainty. What is known is that someone walked up to the tent and attacked from outside, stabbing and bludgeoning through the canvas walls.

Around six in the morning a group of boys out birdwatching noticed the tent lying collapsed on itself. Nearby, they saw a tall blond man walking away from the campsite. They assumed he was another camper, made a note of nothing in particular and carried on with their day.

The bodies were not discovered until almost five hours later. Around eleven, a local carpenter named Esko Oiva Johansson came to the shore and found a scene that would haunt him forever. Three teenagers lay dead or dying around the shredded tent. One more was badly injured but breathing.

Johansson hurried to alert authorities. Police reached the shore around noon. What they did next has been blamed for nearly every unanswered question that followed. Officers failed to seal off the area. Curious locals, reporters and even soldiers brought in to search wandered through the site.

Footprints blurred into each other. Cigarette butts and scraps of paper dropped by onlookers mingled with whatever the killer had left behind. If the ground once told a clear story, that story disappeared under dozens of boots before the first careful photographs could be taken.

The tent itself gave investigators one solid fact. The fabric was slashed from the outside, not from within. Blood patterns suggested blows delivered through the canvas with both a knife and some heavy object, probably a stone or similar weapon. Neither weapon has ever been found.

Inside and around the tent, Maila Björklund, Anja Mäki and Seppo Boisman had suffered severe head wounds and multiple stab injuries. Maila, Gustafsson’s girlfriend, seemed to have been singled out. She had the most injuries, and her body was found partly undressed, lying on top of the tent.

Nils Gustafsson, the only survivor, lay nearby with terrible injuries of his own. His jaw and several facial bones were broken. He had stab wounds and a concussion and slipped in and out of consciousness. When he finally woke in hospital, he said he remembered almost nothing.

He did give investigators one striking image. Gustafsson said that at some point he saw a figure in dark clothing outside the tent, with what he described as bright or even red eyes staring in. The description would later feed decades of eerie rumours and supernatural theories.

In the immediate aftermath, though, detectives had more practical problems. Several items had been taken from the campsite, including wallets and pieces of clothing. The keys to the motorcycles were missing, yet the bikes themselves remained parked nearby, untouched.

Some of the missing clothes eventually turned up. Gustafsson’s shoes were found several hundred metres away, partly hidden in the brush. That suggested the killer had left the area on foot and tried to conceal evidence while escaping, but any tracks that might have led further were long gone.

Police started working through the few solid leads they had. They questioned the birdwatchers, tracked down other campers and families who had been at the lake and tried to map every movement the four teenagers made before pitching their tent. Another name began to surface again and again.

Karl Valdemar Gyllström ran a small kiosk near the lake. Campers already knew him as a hostile presence. Locals said he cut tent lines, knocked over tents and chased visitors who annoyed him. Some claimed he hurled stones at hikers and shouted at children walking too near his yard.

Decades later, books and articles would present Gyllström as the most obvious suspect. Neighbours said that when he drank he sometimes spoke about the murders and hinted that he knew more than he should. His wife first gave him an alibi for the night, then reportedly retracted it, saying he had threatened her.

In 1969, nine years after the murders, Gyllström walked into Lake Bodom and drowned. Many people believed it was suicide. For residents, the story looked complete. An angry kiosk keeper had finally given in to guilt. For police, it did not reach the level of proof. They had no physical evidence linking him to the crime.

Another man soon joined the catalogue of unofficial suspects. Hans Assmann, a German born resident living not far from the lake, had a shadowy biography that already attracted gossip. Rumours tied him to wartime service in Nazi units and to other unsolved Finnish crimes, though many claims remain unverified.

The morning after the murders, Assmann arrived at a hospital in Helsinki in a state that nurses later described as alarming. His clothes were stained with something that looked like blood or mud. He seemed agitated and, according to staff, pretended to sleep when police officers approached. His hair had been freshly cut.

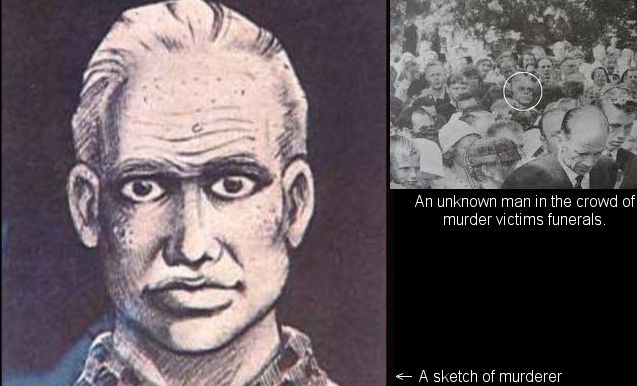

Doctors were concerned enough to mention him to investigators. For the public, the incident became one of the creepiest details in the story. Over time, writers and podcasters lined it up with other facts, including a photograph from the victims’ funerals that appears to show a man resembling both Assmann and an official sketch.

Assmann, however, had an alibi that police eventually accepted. He said he had been in Helsinki with his lover and other witnesses that night, not camping by the lake. Later reviews of the files suggest his alibi was stronger than many people realised, and he was never charged in the case.

With each passing year, the chances of a clean forensic solution dropped. Evidence from the tent degraded. Items taken from the campsite remained missing. Witnesses moved away or died. The Bodom investigation slowly shifted from active manhunt to a national ghost story that refused to settle.

Through all of this, one person carried the weight far more directly than anyone following headlines. Nils Gustafsson married, worked and tried to build an ordinary life. For decades, the official story treated him as a victim and a witness. That changed in the early two thousands.

In 2004, almost forty four years after the attack, Finnish authorities announced that new forensic work had breathed life into the cold case. They quietly arrested Gustafsson, then in his sixties, and charged him with murdering his three friends. To the public, the news felt like the ground shifting.

Prosecutors presented a very different version of the night at Lake Bodom. In their reconstruction, the teenagers had been drinking heavily. An argument broke out, possibly over the girls. Gustafsson, they said, became violent and was punched or pushed out of the tent by Seppo Boisman.

According to this theory, Gustafsson’s jaw was broken in that first fight. Furious and humiliated, he grabbed a knife and a rock and began attacking the tent from outside. Prosecutors claimed he killed Boisman and the two girls in a burst of rage, then staged the scene to look like the work of an unknown intruder.

The key piece of evidence sat for decades in an evidence box. Modern DNA testing confirmed that the shoes found hidden in the woods were Gustafsson’s and identified blood from all three murdered teenagers on them. His own blood, however, was not detected on the shoes.

Investigators argued that this meant his serious injuries must have occurred at a different time. If his jaw and head wounds had been inflicted while he attacked or defended himself from an outsider, they reasoned, his blood should have been mixed with the others on the shoes. Instead, they suggested he moved around uninjured while killing his friends, then injured himself later.

The prosecution tried to reinforce this story with extra details. Two birdwatchers thought the blond man they had seen that morning resembled Gustafsson. A party guest claimed he once made a cryptic remark about the killings. Someone else said he had boasted years later about being responsible.

For the defence, the case looked far more fragile. Gustafsson’s lawyer pointed first to the crime scene itself. It had been trampled by police, reporters, locals and soldiers. With so much contamination, patterns of blood and footprints were almost impossible to interpret with confidence decades later.

Medical experts also described the severity of Gustafsson’s injuries. His jaw fracture and head trauma were not the kind of wounds people ignore. They were the kind that leave someone dazed, unsteady and struggling even to stand. The idea that he had fought three people to the death in that state seemed unlikely.

The defence underlined what prosecutors did not have. There was no murder weapon tied to Gustafsson, no confession, no clear motive beyond a vague claim of jealousy or drunken anger. The entire theory depended on reading a story from bloodstains on decades old shoes pulled from a contaminated scene.

In October 2005, after a closely watched trial, the court delivered its decision. Judges acquitted Nils Gustafsson of all charges. They concluded that the evidence did not prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and that, after so many years and investigative mistakes, it would be impossible to reconstruct the night with certainty.

The Finnish state later paid him compensation for the time he had spent in custody. Newspapers that had spent months hinting at his guilt faced no legal challenge from him. He chose not to sue, and retreated once more from public life.

What remains is a case defined as much by what investigators did not do as by what they tried. Had officers sealed off the tent, preserved tracks in the sandy soil and documented every footprint, Finland might have its answer. Instead, the crucial physical story of that morning was trampled into the ground.

Today the lakeshore looks peaceful again. People walk dogs along the paths and paddle in the shallows in summer. Somewhere under that water, Karl Gyllström’s body once sank. Somewhere in archived boxes sit the tent, the shoes and other fragments of four teenagers’ last night.

Every few years a new podcast, book or documentary returns to Lake Bodom and promises a fresh angle. A blurred funeral photograph, a sketch with strange staring eyes, a new reading of an old statement. Each hints it will finally reveal the face in the crowd, then fades back into the archive.

What does not fade is the outline. Four young people rode out for a night by the water. By midday, three families were planning funerals and one boy lay in a hospital bed with his face shattered. Whoever walked away from that tent between four and six in the morning has never been named.