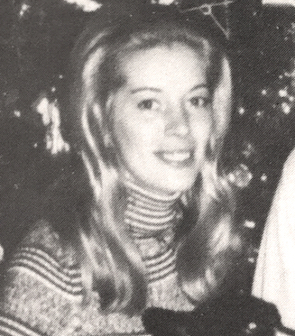

Cindy James grew up under the weight of discipline. Her father, Otto Hack, had worn both an air force uniform and a scowl. He raised her on rules. Corporal punishment wasn’t rare in their British Columbia home. Her private diaries would later whisper about that part of her life—strictness, fear, and distance.

She became a nurse. The kind who showed up early, stayed late, and cared deeply. People called her smart. She had composure. She worked at Vancouver General Hospital before taking a job at Blenheim House, a center for troubled children. Her colleagues trusted her. Patients liked her.

In 1966, she married a man named Roy Makepeace. He was a South African psychiatrist, nearly twenty years older. Her family didn’t like him. Her father said he was manipulative. Her mother stayed quiet. Over time, Cindy began hinting at things—emotional coldness, slaps, fear. She divorced him in 1982.

That same year, she said the terror began.

It started small. A voice on the phone breathing heavily. Then came the threats. “You fucking bitch. I’ll get you.” Another caller whispered, “I’ve got my zipper open, I’m talking to my throbbing…” She told police. They told her to write the calls down. She got an unlisted number. The calls kept coming.

Then the break-ins started. Porch lights smashed. A rock through the window. A slashed pillow. A note pinned to her car with a photo of a corpse. The messages always said the same thing: she would die, and soon. One read: “Soon. Bang bang. You’re dead.”

She didn’t run. She documented everything. She painted her car a different color. She changed homes. She called the police nearly a hundred times between 1982 and 1989.

Still, nothing stopped.

Her basement tenants reported strange noises. A neighbor swore she saw a man near Cindy’s gate, someone who didn’t look like Makepeace. Cindy had mentioned him too—sometimes she defended him, other times she said he’d hurt her. She said he had a temper. At one point, a constable named Patrick McBride moved in to help watch over the house. He later became her boyfriend.

He once found Roy Makepeace parked behind the house. Makepeace said he was there to catch the stalker. Cindy said she didn’t know who to trust anymore.

Later that year, McBride found the phone lines outside the house cut in five places. He saw a note on her windshield with a corpse and the words Merry Christmas.

Things escalated.

One night, her friend Agnes Woodcock came by and found Cindy lying in the backyard. A nylon stocking was tight around her neck. Cindy said two men had attacked her. She said they threatened to kill her sister and inserted a knife into her body. Police couldn’t find evidence of sexual assault, but the strangling had left marks.

Cindy didn’t want to see a psychiatrist. She feared it would discredit her story. She agreed to see a doctor with counseling experience instead.

A week later, she moved houses. Then she got another note: Run, rabbit. I’ll show you how fucking good I am.

She hired a private investigator named Ozzie Kaban. He carried a radio. He gave her one too. One night, he heard strange sounds over the line. When he arrived, she was unconscious on the floor. A paring knife was stabbed through her hand. A note pinned beneath it read: Now you must die, cunt.

Police found a needle mark in her arm but no drugs in her system. She said someone had injected her. She said she’d seen a man coming through the gate before she blacked out.

Kaban believed her.

Blood was smeared in circles on the floor, as if someone had tried to clean up. Cindy took a polygraph. The result was marked “inconclusive.”

But that didn’t stop the next attack.

Collars, Corpses, and a Cat in the Stairwell

In February 1983, Cindy James moved again. This time to West Vancouver. She had barely unpacked before another note arrived. The message was simple: Run Rabbit Run. Soon, bang, bang, you’re dead.

She stopped telling the full story to police. She feared being labelled. But she kept writing everything down. Her house phone rang constantly. At work, her coworkers answered silent calls. Someone was watching her. Someone was listening.

She changed homes again in April. She painted her car. She tried to disappear. The letters still found her.

One note read: Welcome back—death, blood, hate.

She kept her panic button close. She carried pepper spray and oil. She didn’t go anywhere without them.

That autumn, she found three dead cats in her garden. Each had been strangled with rope.

She blamed Makepeace in her private diary. She said he had destroyed her backyard. But publicly, she stayed quiet. He still sent her gifts. He even paid for her to visit her brother in Indonesia.

When she came back, she found another note.

Her private investigator, Kaban, stayed on the case. He believed someone was breaking into her home. He believed she was being hunted.

On January 30, 1984, Kaban heard a strange noise through the radio he’d given her. He rushed to her house.

She was unconscious on the living room floor. A paring knife had been driven through her hand. A note was pinned with it. Letters cut from magazines spelled it out: NOW YOU MUST DIE, CUNT.

Doctors found a needle mark in her arm. They found no trace of drugs.

When she came to, Cindy said a man had entered the gate, hit her over the head, and injected her. Her memory faded after that.

Police weren’t sure what to believe. But one officer, Kiyo Ikoma, noticed something strange: blood smears on the floor, as if someone had tried to clean up. That detail stayed with him.

As suspicion grew, Cindy named Makepeace. She said he was tormenting her.

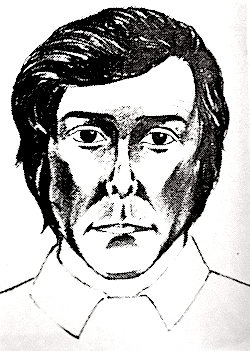

He told police a different story. He said she was caught in some kind of underworld. Maybe the mafia. He said Blenheim House treated children who were wards of the court. Maybe that made her a target.

Cindy’s father didn’t buy it. He met with Makepeace wearing a police wire. He told him to leave his daughter alone.

After that meeting, Makepeace sent Otto a six-page letter. He repeated the mafia theory. He urged Otto to pressure police to investigate.

That summer, things reached a breaking point.

On June 18, Kaban received a panicked call from Cindy. When he arrived, she was hiding in the garden. Inside, her dog Heidi was cowering in the basement. A note lay nearby: Happy Birthday, next to pornographic photos.

Heidi had been tied up and beaten. Kaban said Cindy could never have done that. He also found rope in the basement. It matched the kind used on the dead cats.

There was a cigarette butt on the windowsill. Cindy didn’t smoke that brand.

More calls came. One said: You’re dead, bitch. It’s gonna feel good.

A coworker at Blenheim House got one too. It said: Get rid of the big pig.

On July 1, Cindy said two men came to her door pretending to be police. She radioed Kaban. They fled.

Her mother came to stay a few nights later. That night, they heard the doorbell ring. A window by the porch was cracked.

On July 23, Cindy walked her dog in Dunbar Park. She returned hours later in a daze, trying to enter a neighbor’s house. A nylon stocking was tied around her neck again.

She had puncture marks in her arm. Heidi, her dog, was found wandering the area.

At the hospital, a receptionist remembered something odd. A man with an accent had called earlier. He asked about their security.

When police played a recording of Makepeace’s voice, she said it sounded familiar.

In October, under hypnosis, Cindy said she remembered witnessing a double murder. She said Makepeace was involved.

She gave no names. She gave no place. But something had changed.

A Hypodermic Needle, A Body in a Lot, and a Verdict Nobody Understood

The months that followed felt like borrowed time.

In January 1985, Cindy told police a new story under hypnosis. She said she had seen her ex-husband kill a man and a woman. She said he dismembered their bodies with an axe. She remembered blood on her face. She said they had been at a cabin on Thormanby Island.

Police checked. Her sister Melanie had been there too. Melanie remembered nothing unusual.

Later that year, Cindy overdosed on pills and landed in a psychiatric hospital. She said it wasn’t a real suicide attempt. She just wanted the pain to stop.

Police used that moment to get a wiretap on a call with Makepeace. Cindy confronted him. She told him he was the reason her life had fallen apart. She mentioned the murder she remembered.

He denied everything. He said she was insane. He said she had invented a fantasy world to get revenge.

After the call, the police placed Cindy, Makepeace, and two other people under surveillance. They never found a stalker. They never found a break-in.

The silence stretched out for years. Cindy left her job. She struggled with her health. She continued seeing doctors and counselors.

And then, in 1989, she disappeared.

It was May 25. She had just completed a shift at a local hospital. She dropped off a paycheck. She spoke to a friend on the phone. Then she was gone.

Two weeks passed.

On June 8, her car was found in a neighborhood in Richmond. Groceries were in the back seat. A wrapped gift sat next to them.

Inside, there were bloodstains. A wallet was under the driver’s seat. The keys were gone.

Someone had moved fast.

That same day, a body was found in a yard behind an abandoned house. It was Cindy. She was hogtied. Her wrists and ankles were bound. A black nylon stocking was wrapped around her neck.

The knot was tight.

The autopsy showed a mix of morphine, diazepam, and flurazepam in her system. Sedatives. Enough to kill. But not all at once. Some doses appeared older than others. She had been drugged slowly, maybe over days.

There were no needle marks that pointed to suicide. There were no syringes at the scene. There was no water, no container, no kit. Just her body in the weeds, tied and silent.

Despite this, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police said they found no sign of a crime. No footprints. No fingerprints. They ruled out foul play.

Their final position: she had killed herself.

The public did not accept it.

The coroner ordered an inquest. It began in April 1990. It lasted weeks. More than eighty people testified—doctors, neighbors, friends, police, her family, her ex-husband, her investigators.

The room filled with contradictions.

Some said she was mentally ill. Others said she was calculating and precise. Her private investigator described a woman who lived in fear but remained sharp. Her coworkers said the stalker was real. They had picked up the phone and heard him.

The police insisted she had fabricated it all. They called it attention-seeking. They said no one could tie themselves up like that. Then they showed a demonstration of how it could be done.

The audience sat in silence.

In the end, the jury gave a verdict no one could parse: death by unknown event.

Not suicide. Not murder. Just unknown.

It answered nothing.

Theories, Books, and the Long Echo of Silence

The coroner’s inquest ended without peace. “Death by unknown event” didn’t comfort anyone. It gave nothing to her family. It gave no shame to the police. It gave no justice to the woman whose hands had been tied behind her back.

The RCMP stood by their theory. They said Cindy James had staged her death. They said she had tied herself up. Injected herself. Walked to the abandoned house. And died.

They admitted it sounded strange. But they found no fingerprints. No evidence of a struggle. They said the body showed no signs of restraint injuries, despite the tight knots. They said it was consistent with a planned act.

Experts who testified disagreed.

The drugs in her system would have made it almost impossible to move. She had not just morphine in her blood, but a cocktail of pills designed to sedate deeply. The levels were high. Not instant-death high. But fatal with time. Some had broken down into metabolites, which meant they had entered her system slowly over hours or days. Maybe someone had been keeping her alive—then finished the job.

She had been bound with elaborate knots, the kind used by sailors. Cindy had no sailing background. The position of her arms and legs made movement nearly impossible. Yet police insisted it could be done.

They said she had studied how to fake it. They even suggested she had injured her own dog. They called it a slow-motion suicide stretched over years.

Her family pushed back. They said she had always wanted to live. She had been planning a vacation. She had picked up groceries. She had wrapped a gift. Nothing pointed to death.

Her private investigator, Ozzie Kaban, was more direct. He said Cindy had been murdered. He said someone had been watching her closely. Someone had cut phone lines and left dead cats. Someone had called him while Cindy was away and stayed silent.

She had feared Makepeace. Then defended him. Then feared him again. His voice, according to a hospital receptionist, sounded like the man who had asked about security right before she was found with a stocking around her neck.

No charges were filed.

The story drifted into the media. In 1991, Unsolved Mysteries ran an episode about her. Two books followed: Who Killed Cindy James? by Ian Mulgrew, and The Deaths of Cindy James by Neal Hall. Both drew from trial notes, police files, and interviews.

They told the same story in different ways: a nurse haunted by something no one could see. A woman desperate to protect herself. A system that dismissed her. A case too strange to solve.

In 2021, a podcast revisited it. Death by Unknown Event explored every detail. Host Pamela Adlon read through reports, interviews, and Cindy’s own writings. Listeners were left with more questions than answers.

Why had no one seen the attacker? Why had Makepeace loitered behind her home? Why did the police ignore her mounting panic?

Why did no one believe a woman who documented her own stalking with such obsessive detail?

Years have passed, and the house where she was found has long been torn down. But the photos remain. The notes remain. The police reports remain.

So does the silence.

Cindy James died tied, drugged, and left out in the open.

And whoever did it—if someone did it—never left a name.