Reet Jurvetson’s body was dumped just fifteen feet down a canyon off Mulholland Drive. Close enough to be found. Far enough to be forgotten. She was young, beautiful, and stabbed 157 times. And for nearly five decades, she had no name.

People called her Jane Doe 59. There were no missing persons reports. No leads. No media frenzy. She was buried without a name, without a story, and without anyone asking why.

Until someone recognized her photo online in 2015.

Who was Reet Jurvetson?

Reet Silvia Jurvetson was born on September 23, 1950, to Estonian parents living in Sweden. Her family later moved to Canada, and she grew up in Montreal. She was tall and slender, with dark hair and green eyes. She had vaccination scars on her arm and thigh, a faint scar beneath her breast, and a birthmark on her right buttock.

She had a quiet strength, according to her older sister Anne. In her late teens, Reet worked at a post office in Toronto. That’s where she met a man named John. Or Jean. The name was fuzzy. But she liked him. A lot.

He was mysterious. French-speaking. Said to look like Jim Morrison. Some believed he was a medical student. Reet saved money, packed her things, and followed him to California. Her family knew she was spontaneous and curious. They assumed she was on an adventure. No one thought it would be her last.

How was her body discovered?

On the morning of November 16, 1969, a teenage boy was birdwatching in the hills above Los Angeles. What he saw was not a bird. Tangled in brush off Mulholland Drive, just 15 feet down a steep ravine, lay the body of a young woman. She was fully clothed. Her boots were made in Canada. Her jacket came from Spain. Her belt had a brass buckle, and her fingers wore rings—one white, one yellow, both metal. The yellow one had a red stone.

She had been stabbed 157 times with a pen knife. Most of the wounds were to the neck and chest. Her carotid artery had been cut. Some of the wounds overlapped. Others were deep and deliberate. There were cuts on her hands, clear signs she had tried to fight back. Investigators believed the killer was right-handed, and likely straddled her during the attack. She had eaten two hours earlier. No drugs or alcohol were in her system.

There was no wallet. No purse. No ID. Just a body.

A branch had stopped her from tumbling into a 699-foot-deep canyon. The killer had almost succeeded in making her disappear forever.

What happened next?

The police sketched her face. They photographed her in the morgue. Artists created composite drawings. One of the first versions showed a soft, almost anonymous face. Later versions made her look too old, too square-jawed. None of them looked like Reet. Her sister would later call them wildly inaccurate.

The authorities guessed she was in her early twenties. They had no idea she was just 19. They called her Jane Doe 59. Some nicknamed her Sherry Doe, based on rumors she might have used that name. But no one came forward. No friends. No family. No tipsters. The case stalled immediately.

Her clothing gave a few clues. Some pieces were American. Others weren’t. Her boots and jacket had been made outside the United States. That suggested she was a foreign national. Possibly Canadian. Possibly European. But nothing could be proven.

The body was buried, the file was boxed, and the silence stretched into decades.

Why didn’t her family report her missing?

She had sent a postcard. It was written in Estonian and postmarked October 31, 1969. Just two weeks before her death. She told her parents she was happy in California and had found a place to live. The address she gave was the Paramount Hotel in Los Angeles. She told her best friend the same thing.

Then nothing.

Her parents waited. Weeks passed. They sent someone to the address. The man was told she had moved out. They hired a private investigator. He found nothing. Reet had always been independent. They assumed she would reach out when she was ready.

They never imagined she had been murdered. They never imagined she had been buried as a Jane Doe.

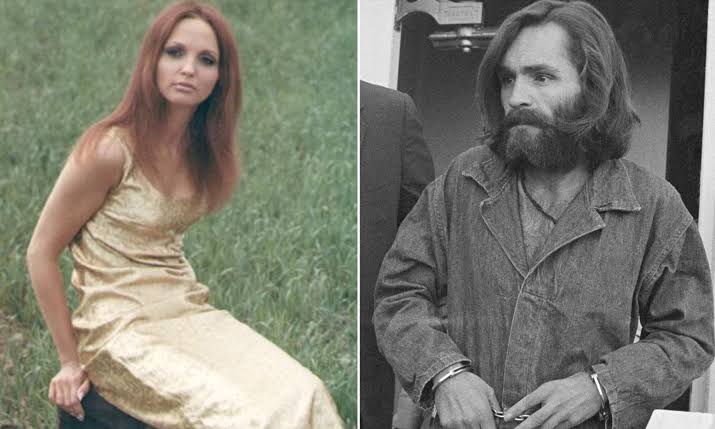

Was the Manson Family involved?

The location of her body was just six miles from the Benedict Canyon home where Sharon Tate and four others had been murdered in August 1969. The Manson Family killings were still fresh in everyone’s minds. The brutality. The chaos. The cult atmosphere. It felt too close to be a coincidence.

Some witnesses claimed they saw a woman matching Reet’s description at Spahn Ranch, the Manson Family’s base. They remembered someone named “Sherry.” Others said Reet had been seen with Family members just days before she died.

Charles Manson was interviewed. He denied knowing her. Police eventually concluded that the Family was not involved. There was no physical evidence. No clear motive. And no confession. Their focus turned elsewhere.

Who was “John” or “Jean”?

Reet had met him at a Toronto post office. Her family described her as smitten. She was careful with money, but she saved enough to follow him to California. That decision sealed her fate.

Witnesses remembered him as having a French accent. Possibly Quebecois. He looked like Jim Morrison. Might have been a medical student. He had a roommate, also French-speaking, with a Beatles-style haircut. Both men were connected to Reet during her final weeks.

One of them told a friend in 1970 that Reet had lived with them. He claimed she left on her own. Said she was fine. Seemed casual about it. But neither man reported her missing. Neither stepped forward when her murder hit the news. Neither tried to help.

Police created sketches based on descriptions from people who had known Reet in Toronto. Those sketches are still part of the open case file. The two men remain persons of interest.

What else did investigators find?

Besides the body, there was something else. A pair of Liberty brand eyeglasses was found about 50 feet from the scene. They were prescription glasses for someone nearsighted. It is unclear whether they belonged to Reet or her killer. They offered no leads.

Investigators also found drag marks in the dirt. They believed Reet’s body had been transported in the back seat of a car, then dragged out and rolled down the ravine. The crime appeared methodical. There was no panic, no rushing. Someone took their time.

The jewelry she wore was examined. The rings were inexpensive, possibly handmade. The belt was plain. Her outfit suggested a mix of practicality and style. She had clearly dressed herself that morning with no idea it would be her last.

How did she finally get identified?

In 2015, a friend of Reet’s stumbled upon an image online. It was a morgue photo of Jane Doe 59 posted on the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. The face looked familiar. She reached out to Anne Jurvetson, Reet’s sister.

Anne submitted a DNA sample. The LAPD still had a bloodstained bra from the crime scene. It held usable DNA. The match came in April 2016.

Jane Doe 59 was Reet Jurvetson.

The family was devastated. They had never considered that she might have been murdered. For years, they assumed she had simply moved on, maybe changed her name, maybe started a new life. Instead, her life had ended almost as soon as it began.

Why did no one connect the dots sooner?

This is what bothers people most. Her photograph was published. Her sketch was shared. Her case was public. Yet no one recognized her. Not in Canada. Not in California. Not even when witnesses reported someone named Sherry in the Manson circle.

The face didn’t look right. The name didn’t match. And the people who knew her best had no reason to suspect the worst.

There was no internet in 1969. No missing persons databases. No way to search coast to coast. Even with best intentions, her family was stuck. They had no tools. No clues. No luck.

What questions still haunt this case?

Why did someone stab her 157 times? That number speaks of rage, of obsession, of something deeply personal. But nothing was stolen. She was not sexually assaulted. She was not involved in drugs or crime. She had barely lived in Los Angeles long enough to make enemies.

Was she betrayed by someone she trusted?

Did she threaten to leave?

Was she caught in something she could not escape?

The level of violence suggests panic or fury. Possibly both. And the silence afterward suggests guilt. The men who knew her fell off the map. The ones she wrote to never got another message.

Where does the case stand now?

It is still open. Detective Luis Rivera has called it active. The LAPD continues to seek tips. They are especially interested in anyone who lived at or near the Paramount Hotel in 1969. They are also trying to locate a neighbor named M. Lindhorst. This person lived across the hall from Reet and may have known her roommates.

The hope is that someone remembers something. A name. A voice. A detail. After so many years, even a small thread could matter.

What does Reet Jurvetson’s story tell us?

Her story is not just about a murder. It is about absence. About the way people disappear, not just from the world, but from memory. For 46 years, Reet Jurvetson was a case number, a sketch, a blank. Her life was filed under Unknown.

And yet she had family. Friends. She sent postcards. She laughed. She loved. She trusted someone who did not deserve it.

When she died, the world moved on. But now that her name has been returned to her, the story will not end in silence.

It ends with questions. And it waits for answers.