On the morning of April 12, 1981, a 14-year-old girl walked into her family’s rented cabin in the rural resort community of Keddie, California. Her name was Sheila Sharp, and she had spent the night next door at a friend’s house.

What she found inside Cabin 28 would become one of the most disturbing and baffling murder cases in American history. Her mother, Sue Sharp, her older brother John, and his friend Dana Wingate were all dead. Her 12-year-old sister Tina was missing. Three younger children, asleep in a nearby bedroom, had somehow survived the night unharmed.

The killers had left behind a scene that defied comprehension—overkill, binding, mutilation, and silence. For decades, that silence endured.

Who was Sue Sharp?

Glenna Susan Sharp—known as Sue—had moved to Keddie in 1980, just a year before the murders. She was a 36-year-old single mother of five children, recently separated from her abusive husband.

Originally from Connecticut, Sue had left her marriage and traveled across the country to start over. She landed in the Sierra Nevada mountains, renting Cabin 28 in the once-popular but fading Keddie Resort.

Keddie wasn’t a place most people moved to. It was remote. The kind of mountain town where people knew each other, and secrets stayed buried under snow. The Sharps lived in relative poverty. Sue received food stamps and enrolled in a federal education program. Despite everything, she was trying to build something better for her children.

The last known hours

On the evening of April 11, 1981, John Sharp, 15, and his friend Dana Wingate, 17, hitchhiked back to Keddie after spending the day in Quincy, the nearby town. They joined Sue at home, where the family had dinner. Sheila left around 8 p.m. to spend the night at the Seabolt residence next door.

Inside Cabin 28 that night were Sue, John, Dana, 12-year-old Tina, 10-year-old Rick, 5-year-old Greg, and their 12-year-old friend Justin Smartt—stepson of neighbor Martin Smartt.

Nobody heard screams. Nobody called the police.

By morning, three people were dead, one girl was missing, and the three youngest boys in the house said they hadn’t seen or heard a thing. The back bedroom door had been closed.

The crime scene

The living room was soaked in blood.

Sue lay on her side near the couch, nude from the waist down, covered with a blanket. Her face had been beaten with such force that her skull was fractured. She had been stabbed in the chest and had tape wrapped around her face.

John lay face-up, his throat slit and head smashed with a hammer. Dana was closest to the wall, face-down, with multiple head injuries and signs of manual strangulation.

There were blood spatters on the ceiling, furniture overturned, and signs of a struggle that had lasted a long time. Whoever had killed them hadn’t just come in, killed, and left. They stayed.

Strangely, there was no forced entry. And in the chaos, someone had taken the time to bind the victims’ hands and ankles with tape and wire.

Sue’s daughter Tina was nowhere to be found.

The boys in the back room

Greg, Rick, and Justin were found safe in the back bedroom. Justin later gave inconsistent stories—first claiming he had dreamed about the murders, then describing vague memories of two men in the room.

In later interviews, he claimed to have witnessed part of the attack, describing Sue being stabbed and Tina being taken out the back door.

His account was dismissed by police at the time. But the details he shared matched the evidence too closely to ignore.

Why wasn’t anyone in the neighborhood awoken by the chaos? The closest house was just 15 feet away. Investigators later found that a neighbor heard “muffled screams” around 1:15 a.m.—but never called it in.

The suspects everyone knew

From the beginning, suspicion fell on one man: Martin Smartt.

Smartt was Justin’s stepfather and a former cook at the Keddie Resort. He lived just across the way, in Cabin 26. On the night of the murders, he claimed he was at the bar with his friend John “Bo” Boubede, a former Chicago cop with a record and alleged mob ties. The two said they returned home and went to bed around 2 a.m.

What they didn’t mention until later was that Martin’s claw hammer had gone missing.

Or that he had been upset with Sue Sharp. According to later reports, Sue had encouraged his wife, Marilyn Smartt, to leave him. Marilyn told investigators that Martin “hated Sue” for that reason.

Martin also gave conflicting stories. In one version, he said he and Bo went to the bar. In another, he said they went for a walk. In yet another, he claimed he passed the time watching TV with Justin. None of it lined up.

And then came the note.

In a 2013 reexamination of the case files, a letter from Martin Smartt to his wife was uncovered. It read:

“I’ve paid the price of your love and now I’ve bought it with four people’s lives.”

Martin Smartt died in 2000. John Boubede died even earlier, in 1988.

They were never arrested.

The girl who vanished

For three years, Tina Sharp was simply missing.

There were rumors she had run away. That she’d seen the murders and fled in fear. That someone had taken her as leverage. But none of it made sense. She was just 12, with no history of running off.

In 1984, a man found a human skull fragment in Camp Eighteen, a remote area more than 60 miles away. A search of the area uncovered a jawbone, a few bones, and a blanket. Dental records confirmed the remains belonged to Tina Sharp.

The discovery raised more questions than it answered. How did her body end up there? Who transported it? Why were her remains left out in the open, unburied?

No cause of death could be determined.

A case frozen by time

From the outset, the case was mishandled. Crime scene photos were incomplete. Evidence was overlooked. Witnesses weren’t followed up with. Even the autopsies were delayed.

Later reports showed the sheriff at the time, Doug Thomas, had a personal relationship with Martin Smartt. Some believe that relationship led to a cover-up. Others think it was just small-town incompetence—the kind that lets murderers slip through the cracks.

Either way, the Keddie case went cold. And the silence stretched into decades.

Why did no one talk?

In the years after the murders, investigators heard whispers. Names were repeated. Hints were dropped. But nothing ever stuck.

The locals spoke carefully. Keddie was a place where gossip could ruin you, and silence was its own kind of survival. A small town doesn’t forget, but it knows how to look away. And for 30 years, that’s what most people did.

The Plumas County Sheriff’s Office eventually closed the case. Martin Smartt and Bo Boubede had both died. Tina Sharp’s death couldn’t be linked to a weapon or timeline. There was no hard evidence tying anyone to the cabin. At least, none that anyone had bothered to look for.

That changed in 2013.

Reopening the box

The case was officially reopened by Plumas County Special Investigator Mike Gamberg, a former deputy sheriff with ties to the original investigation—and his own doubts about how it was handled. He knew something wasn’t right. He had grown up in the area. He knew the Sharp family. He also knew that no one in 1981 had taken the case as seriously as they should have.

Gamberg started from scratch. He combed through old case files and evidence boxes that had sat in storage for decades. And what he found confirmed what many had long suspected: crucial evidence had been ignored, and leads had been left dangling.

A sealed envelope marked “Do Not Open” contained the infamous letter from Martin Smartt to his wife. A handwritten confession, possibly never acted on. Worse, a tape recording of a call made to the Butte County Sheriff’s Office in 1984—right after Tina’s skull was found—had never been passed along to investigators in Keddie.

The voice on the tape? An anonymous male claiming to know the location of Tina Sharp’s remains—before they were publicly identified.

It had been buried in an evidence box for thirty years.

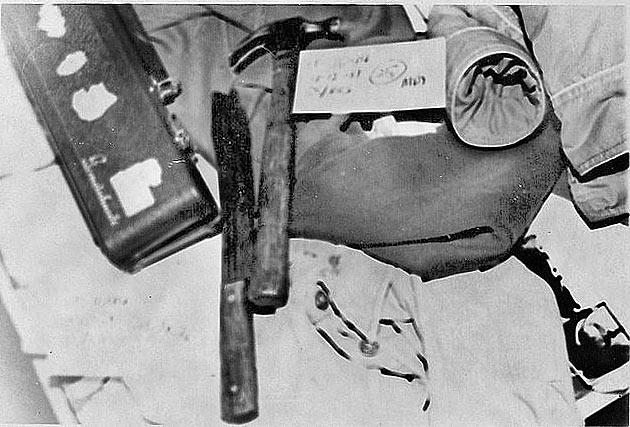

The hammer in the pond

Then came the hammer.

In 2016, investigators recovered a claw hammer from a dried-up pond near the crime scene, just where Martin Smartt had once said his had gone missing. It was rusted but intact—an exact match for the kind of weapon believed to have been used in the murders.

Was it the murder weapon? Possibly. But after decades in the elements, any DNA or blood evidence was long gone. The find added weight to Smartt’s guilt—but not enough for a conviction.

There was also new analysis done on physical evidence from the cabin: pieces of medical tape, electrical wire, and carpet fibers. When tested, they yielded a partial DNA profile—enough to point to a living suspect.

The sheriff’s office refused to name them publicly. But the implication was clear: someone connected to the case, someone still alive, had left their DNA behind at the scene of one of the most gruesome unsolved crimes in state history.

Still, no arrests followed.

What about Justin?

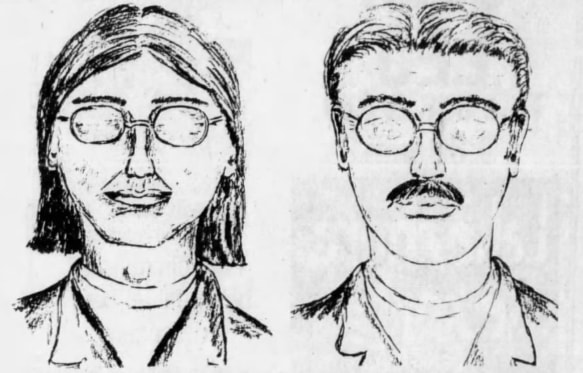

The boy in the back bedroom—Justin Smartt—had always been a wild card. In his earliest statements, he claimed he had dreamed the murders. Later, he recalled a fragmented scene: two men, one with a mustache and long hair, attacking Sue while Tina looked on. He said Tina had been taken out through the back door.

At the time, his story was dismissed as a child’s imagination. But years later, after re-interviewing him as an adult, investigators found his descriptions lined up with the evidence. He had known things he should not have.

Was he a witness? A participant? Was he told to keep quiet? No one knows.

But what is clear now is that Justin may have been the only person awake when the killers came in—and he might have seen much more than he ever admitted.

Connections that never added up

There were other strange overlaps. Martin Smartt had allegedly served in the military with Bo Boubede. Yet no records of Boubede’s military service or time as a Chicago police officer could ever be confirmed. Some suspect he gave a fake name entirely—John “Bo” Boubede was likely an alias.

The two men moved in together shortly before the murders. They were reportedly seen arguing with Sue Sharp in the weeks leading up to the killings.

A counselor at the Veterans Administration later claimed that Martin had confessed to him about the murders during a therapy session. He allegedly said he was “upset about Sue breaking up his marriage” and that he “had to do something about it.”

That confession was never followed up.

Why? Because the original sheriff, Doug Thomas, reportedly dismissed it—and then quietly left office. He later denied any misconduct, saying he believed the case was “just too complex to solve.”

But the question remains: was it too complex—or just too inconvenient?

A system that looked away

There’s a pattern that runs through the Keddie murders—not just of brutality, but of obstruction. Important pieces of evidence disappeared. Witnesses weren’t interviewed. Notes went missing. Statements were never written down.

When new investigators began reconstructing the timeline in the 2010s, they found gaps everywhere.

Some believed there had been a cover-up. Others said it was just laziness. Either way, the result was the same: the killers got away.

The case, reopened after 30 years, now faced the challenge of solving a murder with no physical evidence left, no living suspects in custody, and a community still hesitant to speak.

Gamberg and others working the cold case have continued collecting leads. They believe at least two people were involved, that Tina was taken as a hostage or a witness, and that her murder was meant to silence her. But without a confession or new forensic evidence, the case remains officially open, but stalled.

What we know—and what we probably never will

We know three people died violently in Cabin 28. A fourth vanished, only to be found years later in the woods.

We know the suspects were known to the victims. We know they were never charged.

We know the investigation was flawed from the start—and the system failed the Sharp family more than once.

What we don’t know is how many people were involved. We don’t know what really happened between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m. on April 11, 1981. We don’t know who moved Tina’s body—or who watched the boys sleep in the back room while their mother was murdered in the front.

The cabin has long since been demolished. Nothing remains of the Sharp home but a clearing in the woods. But the case still lives on in documents, in photographs, and in the people who have refused to let it fade into legend.

Some wounds bleed once. Others, for decades.

The Keddie Cabin Murders are not just a story of what was done—but of what wasn’t. Of names unspoken, evidence ignored, and children who grew up with silence in the shape of a scream.

Has the M-Vac system been used in this investigation, or could it be considered? In a case with multiple victims, especially if clothing, bedding, or vehicles were involved, the M-Vac could help find touch DNA or other biological evidence that regular swabbing might miss — even if it’s degraded or mixed. This might be especially useful if the items were exposed to the environment or hard to sample.