A thriving Black community was destroyed in less than 24 hours. For decades, history tried to forget it.

In 1921, the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a beacon of Black success. Built by Black residents, for Black residents, it flourished despite the racial barriers of the time. Greenwood had homes, businesses, churches, schools, and an economy that thrived independently of white Tulsa.

Then, in a span of just 24 hours, it was gone.

What happened was not a riot. It was not an accident. It was a massacre, carried out by a white mob intent on destroying Black prosperity. And for decades, this dark chapter of American history was systematically erased.

Note: Photos from the aftermath of the Tulsa massacre reveal the devastation left behind. See them at the end of the article.

According to a New York Times investigation, which reconstructed the neighborhood through archival maps, photographs, and survivor testimonies, hundreds of Greenwood residents were killed, more than 1,250 homes were burned, and entire generations lost the wealth that could have shaped their futures.

Greenwood: A City Within a City

At the time, Greenwood was one of the most prosperous Black communities in America, often referred to as “Black Wall Street.”

In the early 1900s, Black entrepreneurs built businesses, churches, and homes on land purchased by pioneers like O.W. Gurley and J.B. Stradford. Segregation laws, which were meant to limit Black economic opportunity, ironically helped Greenwood thrive—since Black residents were barred from white-owned businesses, they invested in their own.

By 1921, Greenwood had its own schools, grocery stores, newspapers, hotels, doctors, and theaters. The 100 block of Greenwood Avenue was the heartbeat of the district, lined with over 70 businesses, most Black-owned.

- The Williams Dreamland Theatre offered silent films and live performances.

- The Tulsa Star, a Black-owned newspaper, reported on racial injustice.

- J.B. Stradford’s Hotel was one of the finest accommodations for Black travelers in the country.

You could eat dinner, see a show, shop, get a haircut, and go to the doctor—without ever leaving the neighborhood.

This was a self-sustaining economy that provided financial independence and upward mobility for Black families.

And that, historians say, is exactly why it was targeted.

The Night Tulsa Burned

On May 30, 1921, a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner named Dick Rowland entered an elevator in the Drexel building, where 17-year-old Sarah Page, a white elevator operator, was working. What happened next is unclear. Some accounts say Rowland tripped and accidentally grabbed Page’s arm. She screamed. He ran.

The next day, the Tulsa Tribune ran a sensationalized front-page story accusing Rowland of assault. A white mob gathered outside the courthouse, demanding that he be lynched.

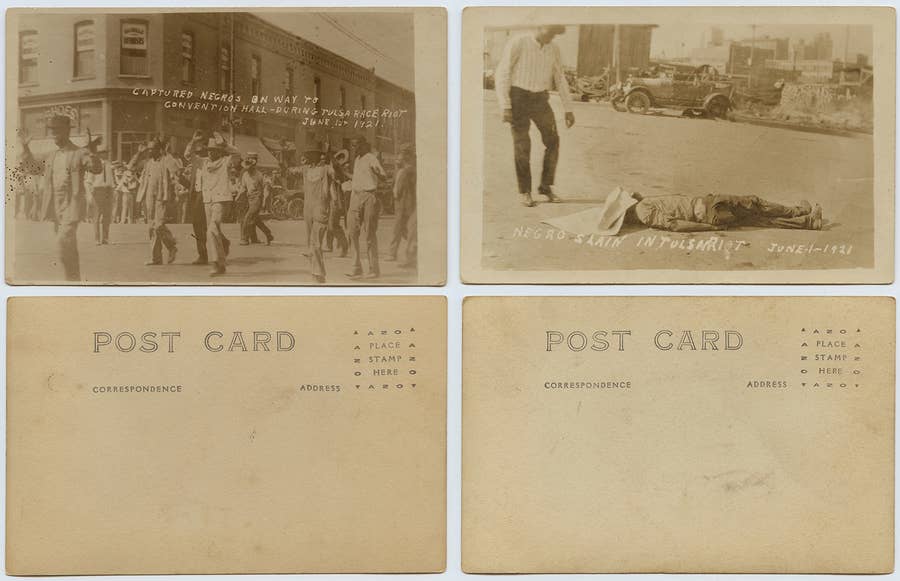

When a group of armed Black men—many of them World War I veterans—arrived to defend Rowland, shots were fired.

What followed was a violent, organized attack on Greenwood.

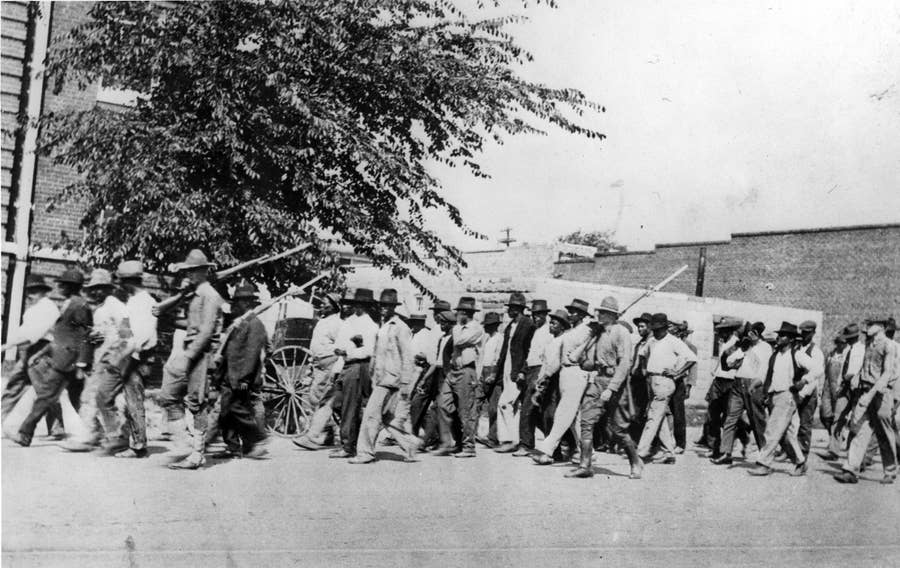

- White mobs, many deputized by local officials, marched into Greenwood, looting and setting homes on fire.

- Black residents fought back, but they were outnumbered and outgunned.

- Airplanes were used to drop incendiary devices, one of the first aerial assaults on an American city.

- Survivors recalled seeing bodies thrown into the Arkansas River or buried in mass graves.

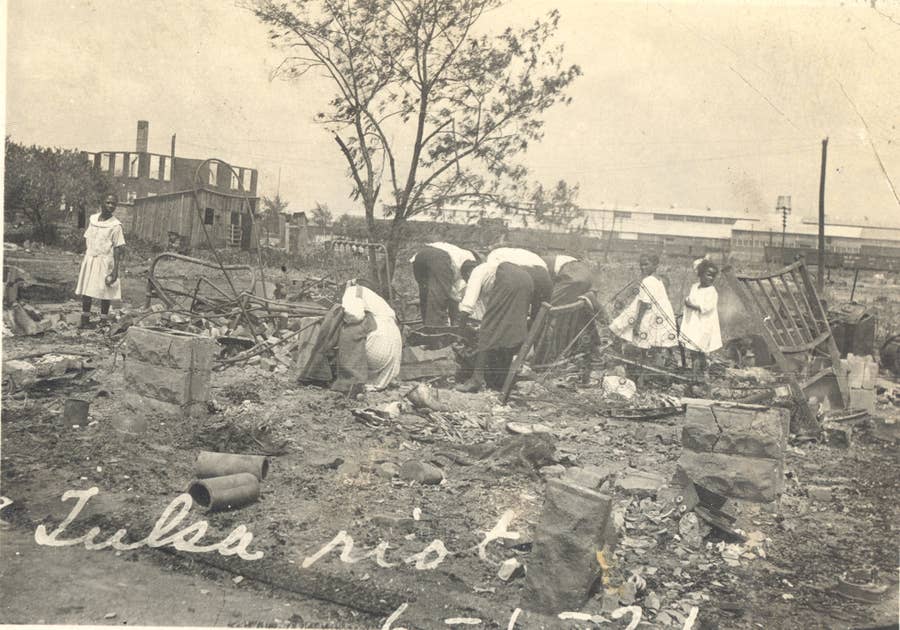

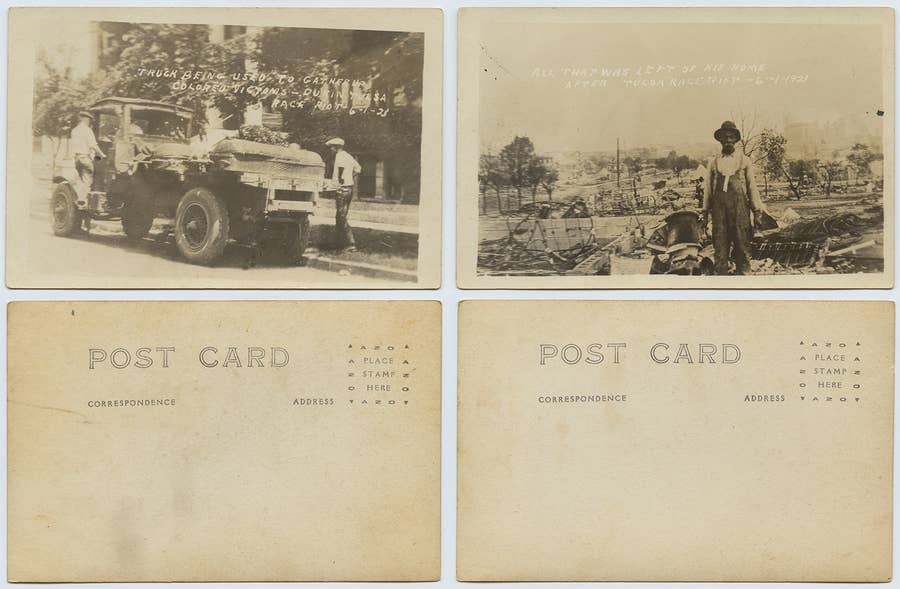

By the morning of June 2, 1921, Greenwood was unrecognizable—35 blocks reduced to ashes.

The Aftermath: Silence and Lost Wealth

In the days following the massacre, the Black community was blamed for its own destruction. Survivors were forced into internment camps, where they had to carry green identity cards to leave. Insurance claims for property loss—totaling what would be $27 million in today’s money—were denied.

Most survivors received nothing.

“If we had been allowed to maintain our family business, there’s no telling where we could be now,” said Brenda Nails-Alford, whose grandfather’s shoe shop was destroyed.

Without homes, jobs, or resources, many Black families left Tulsa forever. Those who stayed rebuilt, but Greenwood was never the same.

Decades of Cover-Up and Silence

For years, the Tulsa Race Massacre was deliberately erased from history.

- The incident was not taught in schools.

- Documents mysteriously went missing from archives.

- The front-page Tulsa Tribune article that helped incite the massacre was cut out of physical copies of the newspaper.

It wasn’t until a 2001 state commission report confirmed the extent of the massacre that mainstream recognition began.

Even today, no one has ever been prosecuted for the attack.

What Was Lost?

The massacre didn’t just destroy buildings—it wiped out generations of Black wealth.

A New York Times analysis of census data and survivor testimonies found that:

- Before the massacre, 40% of Greenwood residents were professionals, skilled workers, or business owners.

- By 1930, most of the surviving families were forced into poverty.

- The massacre exacerbated the racial wealth gap, the effects of which still linger today.

Hannibal B. Johnson, a historian and education chair for the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, put it bluntly:

- “Greenwood wasn’t a gift from anyone. It was built by Black people who withstood the tragedy of 1921 and rebuilt it again.”

But the question remains: What would Greenwood have become if it had been left alone?

Justice, a Century Later?

In recent years, there has been a renewed push for reparations. A lawsuit filed by survivors and descendants seeks financial compensation, but no reparations have ever been paid.

Tulsa officials have started searching for mass graves, but full accountability remains elusive.

For many, justice is long overdue.

“Greenwood was a success story, and that’s why it was attacked,” said historian Scott Ellsworth. “But it is also a story of resilience.”

A century later, the fight for Greenwood’s legacy continues.

Don’t Miss: The mysterious death of LaVena Johnson: a suicide, or a military cover-up?

The Aftermath in Pictures

Final Thoughts

This article is based on archival research, survivor testimonies, and data analysis conducted by The New York Times. Their investigative work reconstructed Greenwood in 3D models, analyzed 1920 census data, and uncovered documents long thought to be lost.

Even today, many Americans are just learning about the Tulsa Race Massacre for the first time. The question is: What do we do with this knowledge now?