After 46 years of grit, sweat, and a whole lot of shoveling, China has done the unthinkable: it planted a 3,046-kilometer-long green belt around the Taklamakan Desert.

Known as the “Sea of Death” for its ability to swallow adventurers whole, this inhospitable sandbox is now hemmed in by millions of trees, all part of the nation’s ambitious battle against desertification.

As the Global Times triumphantly reported, the last 100 trees were planted last Thursday in Yutian County, Xinjiang. This milestone marks the completion of China’s “Three-North Shelterbelt Project,” a 1978 brainchild of Deng Xiaoping that sought to rein in desert expansion across northern, western, and northeastern China.

Think of it as a leafy Great Wall, but instead of stopping invading armies, it’s here to halt sandstorms.

Deserts, dust, and defiance

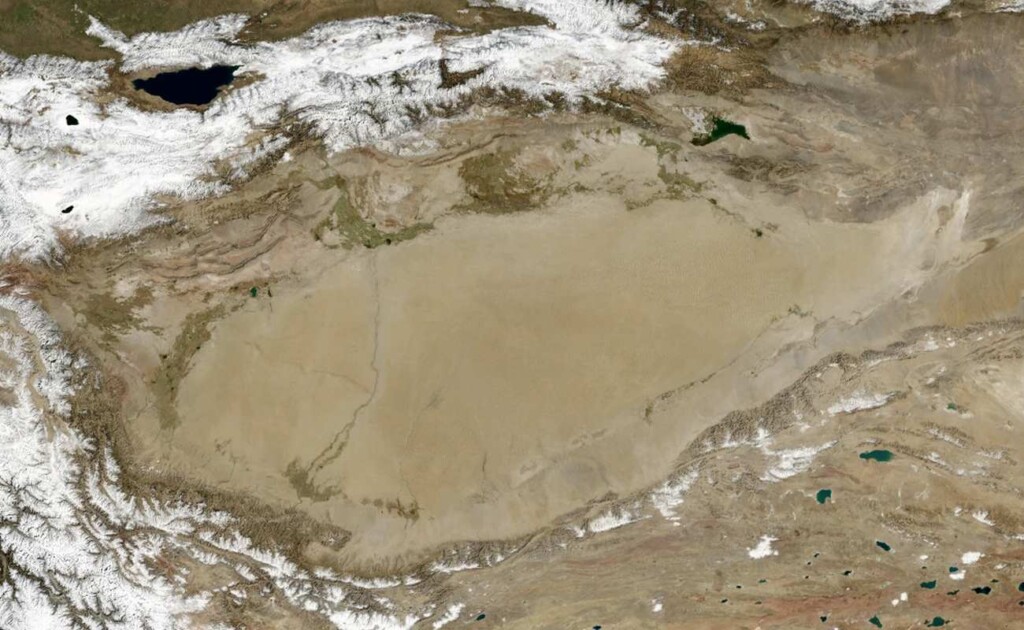

The Taklamakan Desert is no ordinary stretch of sand. Covering 337,600 square kilometers, it’s the largest desert in China and the second-largest shifting-sand desert in the world.

It’s also the farthest point from any ocean on Earth, which means it doesn’t just have a bad attitude, it’s also a little lonely.

The desert’s name, depending on who you ask, translates to “Go in and don’t come out,” a reputation it’s fully earned.

Since the late 1970s, desertification has plagued China’s poorest regions, bringing sandstorms that choke the air, threaten farmland, and make life generally unpleasant.

The Three-North Shelterbelt was created as a solution: 30 million hectares of trees (that’s 116,000 square miles) planted over four decades to act as a natural barrier.

The results? Mixed.

Forest coverage in China has jumped from just 10% in 1949 to over 25% by the end of 2023, according to state reports.

In Xinjiang, one of the most affected regions, coverage rose from 1% to 5%. But not every sapling lived to see its prime.

Poor species selection, insufficient irrigation, and occasional beetle infestations have caused waves of die-offs, turning parts of the project into expensive mulch. As Reuters delicately put it, “survival rates have often been low.”

Critics have also raised concerns about water usage, arguing that siphoning off groundwater for tree planting could be as risky as desertification itself. However the initiative did shrink the Gobi Desert by 2,000 square kilometers in 2022 and made a measurable dent in China’s carbon emissions.

So, sand: 0, trees: 1.

A green future or a patchy past?

Last week’s planting capped a years-long effort to seal the final 285-kilometer stretch of the Taklamakan green belt. This section, running along the southern edge, faced the toughest conditions yet, including extreme wind and sand hazards. But science and strategy prevailed.

Officials paired hardy species like poplars, sacsaoul, and desert willows to endure the harsh climate, according to Xinhua News Agency.

“After four decades of planting, we’ve gotten much better at choosing the right species for these environments,” Zhu Lidong, a Xinjiang forestry official, said during a press briefing.

He noted that restoration efforts are ongoing, particularly in the desert’s northern and western edges, where officials plan to divert floodwaters to sustain poplar forests and build new forest networks to protect farmland.

And it’s not just about trees anymore. Economic incentives are being woven into the project’s next phase, with plans for orchards and sand-tolerant crops like cistanche to improve the livelihoods of local residents.

“The belt ensures agricultural stability and enhances urban living conditions while promoting economic growth,” Tuhti Rahman, director of Xinjiang’s forestry and grassland bureau, told Xinhua.

Not quite a happy ending, yet

While the “Green Great Wall” is a monumental achievement, it’s still a work in progress.

China aims to expand the Three-North Shelterbelt through 2050, with a vision of creating an “unbreakable ecological security barrier” across 42% of the country’s total land area.

So far, it’s covered 4 million square kilometers, increasing forest coverage in project areas from 5.05% in 1978 to 13.84% today.

Still, challenges remain.

Official data from the forestry bureau shows that 26.8% of China’s land is still classified as desertified, a slight improvement from 27.2% a decade ago, but nothing to plant a victory flag over just yet.

As for the Taklamakan, its sandstorms are far from defeated. But for a desert infamous for the warning “don’t come out,” it seems the trees are here to stay, and they’ve got reinforcements coming.